You said things I wouldn’t say straight to my face, boy

You tossed the egg up and I found my hands in place, boy

After backing up as far as you could get

Don’t you know nobody parts as rivers met?

Don’t you know I’m very happy?

You know me well, I’m even happier I like it, I like it

With all of the time in the world to spend it

Wild and unwise, I wanna be mesmerizing too

Mesmerizing too

Mesmerizing to you

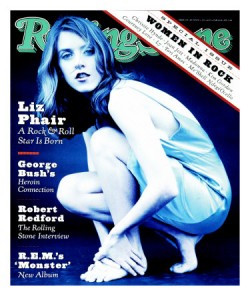

There are a lot of bands and artists that define my teenage years: the Pixies, Sonic Youth, the Beastie Boys, PJ Harvey, but none more so than Liz Phair. Phair’s seminal debut album Exile in Guyville was the record I listened to the most and the one that best captures the desire, anger, ambition, bravado and hope I felt as a young woman. Unlike the glorious mess of Courtney Love or the older and impossibly cool Chrissie Hynde or Debbie Harry, Phair seemed accessible to me. The Chicago of Phair’s album was only three hours from my home in Kalamazoo; it was the big city where we visited museums and saw shows and Phair was like the older sisters of my best friends, whom I secretly worshipped. These girls were smart, knew everything about music and had wry, Dorothy Parker-type personas, a toughness I mimicked to cover my own insecurities. I felt an immediate and deeply personal connection with Exile, I felt like I knew who Phair was and knew the people she was describing in her clear-eyed, poignant lyrics.

There are a lot of bands and artists that define my teenage years: the Pixies, Sonic Youth, the Beastie Boys, PJ Harvey, but none more so than Liz Phair. Phair’s seminal debut album Exile in Guyville was the record I listened to the most and the one that best captures the desire, anger, ambition, bravado and hope I felt as a young woman. Unlike the glorious mess of Courtney Love or the older and impossibly cool Chrissie Hynde or Debbie Harry, Phair seemed accessible to me. The Chicago of Phair’s album was only three hours from my home in Kalamazoo; it was the big city where we visited museums and saw shows and Phair was like the older sisters of my best friends, whom I secretly worshipped. These girls were smart, knew everything about music and had wry, Dorothy Parker-type personas, a toughness I mimicked to cover my own insecurities. I felt an immediate and deeply personal connection with Exile, I felt like I knew who Phair was and knew the people she was describing in her clear-eyed, poignant lyrics.

Released in 1993, Exile is famously lo-fi, but the truth is that the album contains an astonishing variety of styles and sounds — everything from solid rock, haunting solo piano pieces, power pop, folk songs to indie rock. There is also a surprising depth to the writing; Phair’s music matches her sharp, vivid words, whether it’s the evocative “Stratford-on-Guy,” the mature clarity she uses to describe the end of a long-term relationship on “The Divorce Song” or the macho posturing of “Fuck and Run.” And then there’s Phair’s voice, her deadpan monotone imbues many of the lyrics with a sly, winking humor or brings needed understatement to the most outrageous lines (“Fuck and run, fuck and run. Even when I was seventeen. Fuck and run, fuck and run, even when I was twelve…”)

The songs that would become Exile in Guyville were written over a number of years in classic indie fashion — on a four-track cassette player in Phair’s bedroom. She also infamously patterned the record after the Stones’ Exile on Main St. In a 2008 NPR interview on the 15th anniversary rerelease, Phair clarified that there was a guy she had a crush on in the scene in Wicker Park, the Chicago neighborhood that served as inspiration for the Guyville of her record. She said that he became identified in her mind with Mick Jagger’s character in Exile on Main St. and the songs were mostly written as a series of imagined responses to this man.

Phair’s frank and sexually charged lyrics garnered a lot of attention from critics at the time and, I’ll admit, they were the first thing to catch my 16- year-old attention. There was no fucking and running during my virginal teen years or, indeed, during my chaste adult life, but there was something exhilarating about hearing a woman talk about sex in such a matter-of-fact way and it was a relief to hear a girl talk about being as horny (I’m cringing as I write that word, but that is exactly what it was) as the boys. As Phair says, “I feel like I had been listening to records for 10 years where guys talked explicitly about sex. Women were sort of shunted to the area of emotion. But I’ve always been really pissed off, frankly, [about] that whole myth that women aren’t interested in sex. If you had 30,000 years of really bad consequences for being interested in sex, you might hide it, too.” Even now, 15 years later, Exile’s lyrics still seem bold — an indication that we continue to live in a society where women are expected to be sexy, but not necessarily sexual. Phair’s awareness of the power of her sexuality is coupled with big questions about how to use it and the sometimes fine line between being sex positive and playing into harmful, business as usual, notions about women and sex.

year-old attention. There was no fucking and running during my virginal teen years or, indeed, during my chaste adult life, but there was something exhilarating about hearing a woman talk about sex in such a matter-of-fact way and it was a relief to hear a girl talk about being as horny (I’m cringing as I write that word, but that is exactly what it was) as the boys. As Phair says, “I feel like I had been listening to records for 10 years where guys talked explicitly about sex. Women were sort of shunted to the area of emotion. But I’ve always been really pissed off, frankly, [about] that whole myth that women aren’t interested in sex. If you had 30,000 years of really bad consequences for being interested in sex, you might hide it, too.” Even now, 15 years later, Exile’s lyrics still seem bold — an indication that we continue to live in a society where women are expected to be sexy, but not necessarily sexual. Phair’s awareness of the power of her sexuality is coupled with big questions about how to use it and the sometimes fine line between being sex positive and playing into harmful, business as usual, notions about women and sex.

But, there is so much more to Exile than sexual frankness. Exile is about finding your way in the third wave of feminism, when you believe in equality, but you aren’t quite sure how it is supposed to look. There is a lot of repressed good girl anger being let loose on Exile, music critic Laura Sinagra says Phair’s “genius has always been for fantasies sprung from the precise pen of the passive observer. Her first songs weren’t about thinking on your feet, or slinging zingers at the straw-man rockboy she called “Johnny Sunshine;” they were about crafting retorts later in your bedroom and living off their power.”

There is a small incident that occurred during my freshman year at BYU, which, for me, captures exactly this element of the album. My friends and I moved in the same circles of a collection of punkish ska bands, not entirely unlike the cooler-than-thou denizens of Guyville. We were not in the inner circle, but there were crushes, hanging out and some dates with the guys in the bands. Towards the end of the year, I was hanging out with a boy I had a crush on and we went back to Deseret Towers to get a King Crimson CD he wanted me to hear. While there, we ran into the lead singer in the most successful of these bands. He greeted us coolly, looked me up and down and said,

“Why are you wearing red lipstick?”

Running through my head was something like the following: I’m wearing red lipstick because I think it’s cool and striking, it reminds me of old movie star glamour, Debbie Harry and Twin Peaks. I’m wearing it because boys who want freshly-scrubbed girl-next-door types are turned off by it and those dudes and I have nothing to say to each other. Wait a second, why should I have to explain myself to you? It is none of your business…

But instead of saying any of that, I shrugged my shoulders and smiling uneasily said, “I don’t know, I like it.”

“I think girls look better without makeup. You also dyed your hair, didn’t you,” he said, looking at the area above my head, as though my actual face and eyes were beneath his attention. And, in case I had missed the full extent of his disapproval, he added, “You look like you are trying too hard.”

Ah, yes, I was breaking one of the cardinal rules of female beauty — trying too hard. Because men want us to look like we’ve made an effort, but too much of an effort is distasteful. We should wear makeup, but it should be natural, we should eat with gusto on dates to suggest our appetites in other places (wink, wink —in the bedroom), but our bodies should never show the consequences of that passion. We should exercise, but never seem too obsessed with it — and on and on.

Filled with shame, I tried to answered him bravely, but I lacked conviction when I said, “I don’t care if guys like it, I do.”

He shrugged and looked at his friend, rolling his eyes with a condescending “she doesn’t get it” smile playing on his lips as I escaped with my crush, feeling humiliated.

I was angry with this guy for being a jerk and trying to put me in my place, but I was angrier with myself. Angry that I didn’t know what a good feminist or a good Mormon (those two things always competing in my mind) was supposed to look like. I was angry that I hadn’t told him to mind his own business without fear of sounding like a bitch. And, I was angry that I was lying when I said I didn’t care if guys liked it, because I did care, even though I wished I didn’t.

As small as it was, the incident haunted me for years. On days when I was putting on red lipstick or just feeling low, I would suddenly find myself replaying it all in my head and imagining all the things I should have said to him. His behavior seemed like bad manners, but it didn’t even occur to me that my appearance shouldn’t have been up for his evaluation or comment or that I was free to completely ignore him, not feeling the pressure to bend myself as much as possible into the preferences of every man I met. As a young woman, I knew that my appearance was there to be evaluated by others — to be deemed desirable or undesirable, modest or immodest, pretty enough or not pretty enough — by everyone, but me. I didn’t realize that I could be at the center of my own experience of my body until I was much older and it took me years to figure that I didn’t owe him any explanation at all.

Reflecting on Exile in the NPR interview, Phair said “I hear how unhappy I was. As much as I was taking a tough stance, acting tough, it’s so clear to me now how unsure and vulnerable I really was. It is really such a portrait of a vulnerable young woman trying to establish some power for herself.” So many things about being a young woman — wanting to be mesmerizing, as mesmerizing as the men and mesmerizing to them, wanting, but failing to speak up for myself, trying to figure out how to be empowered by my sexuality instead of shamed or owned by it and being pissed off — were first articulated for me through Exile. Listening to Phair as she tried to find her voice, helped me find my own.

Reflecting on Exile in the NPR interview, Phair said “I hear how unhappy I was. As much as I was taking a tough stance, acting tough, it’s so clear to me now how unsure and vulnerable I really was. It is really such a portrait of a vulnerable young woman trying to establish some power for herself.” So many things about being a young woman — wanting to be mesmerizing, as mesmerizing as the men and mesmerizing to them, wanting, but failing to speak up for myself, trying to figure out how to be empowered by my sexuality instead of shamed or owned by it and being pissed off — were first articulated for me through Exile. Listening to Phair as she tried to find her voice, helped me find my own.

For a listen, click on any of the song titles.

This is was an excellent read. On an aside, waht do you think of her newer stuff?

Thank you Aaron.

Her newer stuff is largely disappointing. There are a few gems on Whip Smart and Whitechocolatespaceegg, but I haven’t liked any of the subsequent albums. I don’t begrudge Phair for wanting to try other things and not being able to reproduce the genius of Exile in Guyville; I think she was the right voice in the right place at the right moment.

Heidi, I enjoyed your retrospective on the intersection of Phair’s music with your life. I also like the sly title of the post, given her lyrical tendencies. I missed her earlier work, but I remember seeing her perform (“Supernova”?) on David Letterman once and I was an immediate fan. Chalk it up the cool guitar work or my weakness for women playing electric guitars or how freshly unorthodox her bold lyrics were.

Thanks Ed.

I love “Supernova” — it’s a great song.

Heidi, you’ve summed it up for so many of us! The Divorce Song has always been one of my all-time favorites. For me, I think part of the allure with listening to this album is that it’s tough and risqué, but oh so easy to sing along to. Whip-Smart has a lot of goodies too, not quite as raw as Exile.

Thanks Jess. “The Divorce Song” is also my favorite on the album; although, it is one of those albums where all the tracks work together — and you’re right, there a lot of catchy tunes. I also think it’s the push and pull between vulnerability and toughness, prettiness and sharpness, sexiness and anger, makes the album so compelling.

Heidi, I enjoyed the personal touch of this review.

As I think I told you before, I picked up the 15th Anniversary edition of Exile a couple years ago. Great stuff, although I wish I had absorbed it during its original context — both its musical context (juxtaposed against other early 90s albums), and my personal context (as a questioning RM at BYU who derived more soul food from music, books, and movies than from church).

Weird that I never heard Exile back in the day, since I bought Whip Smart when it came out a year or so later in ’94. In those pre-Internet days, unless you (or a friend) owned the CD, or it got some radio play, you just didn’t hear it. It wasn’t an Alannis-style mega-hit record, but a super “indie” record. Too indie for alternative radio. And really lo-fi (unlike Whip Smart). Time has brought Exile more recognition, but at the time Liz was just buzz in the pages of the music rags and on the lips of red-lipstick-wearing scenesters like Heidi. ;)

@ Matt, I agree about context — aside from my personal connection with the album, I think Exile occupies an interesting moment for both music and feminism. It is that moment before Phair’s (and other feminists’) sex positivity and frankness degenerates into Girls Gone Wild, the moment before Kathleen Hanna writing “Bitch” on her stomach evolves into teenage girls running around the mall with “Princess” and “Brat” emblazoned across their T-shirts. The moment before the themes of Phair’s album are carried into the glossier and highly produced Alanis Morissette. (Although, I realize it is typical of a scenester to decry whatever becomes popular :).)

I was reading Elizabeth Wurtzel’s “Prozac Nation” and watching Winona Ryder in “Reality Bites” and listening to P. J. Harvey’s “To Bring You My Love” and Shirley Manson’s (Garbage) great self-titled first album around the same time as I was listening to Liz Phair’s “Whip Smart”. (All during ’94 and ’95.) All five women were/are within one or two years of my age. Thinking about them brings me back to the apartments I lived in at that time, the cars I drove, the girls I dated…

I have no idea which of these women were/are considered real feminists, but I crushed on all of them at the time in large part because they seemed to me so strong, smart, and self-possessed.

@Matt, I always feel cagey and unsisterly when it comes to judging another woman’s feminism, but I know all of the women you listed influenced my feminism and I admired them (girl crushes? There has to be a better way to express that.) for the same reasons you listed. That period includes my last few years of high school and my first few years of BYU and also makes me incredibly nostalgic.