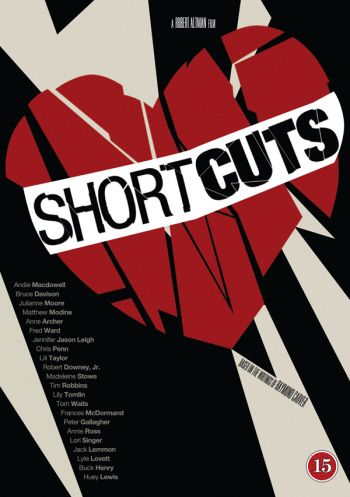

Short Cuts (1993) is a film based in LA. That’s a problem, for me, because LA is not like most places in the world: certainly not like the backwoods locations that Raymond Carver selected for most of the stories that the film bases itself on. But for Altman, moving the stories from the Midwest/Pacific Northwest to the home of Hollywood cinema was an essential move: he felt that it gave a reason for the characters lives to intersect, in a way that was suggested in Carver’s poem ‘Lemonade’. Thus, in Short Cuts, characters from separate stories pass and meet each other at concerts, in bakeries, and in the street. These meetings are moments of conflict and recognition: and, occasionally, of horror.

The thematic interest in connection and disjunction is expressed technically for Altman, whose pioneering use of multi-track technology in filmmaking comes to the fore in Short Cuts, which connects the episodic scenes by the use of music: a concert cellist and her bar-singing mother provide the musical backbone of the film. The sound of helicopters, too, unites the city, which is being sprayed for control of the ominous ‘medfly’ that has become rampant. Elsewhere, televisions and telephones flash and ring in so many scenes: a sign of the personally distant yet media-connected culture that the home of studio cinema epitomised.

So: how do you read Short Cuts? Ironically, it’s a very long film: it needs to be to compress so many narratives into (even an urban) package. Carver’s writing is deceptively minimalist in appearance: other filmic adaptations have used a single story to expand. The result is that we feel like we’re dipping into these characters lives at their most vulnerable and human points: a common sense in the textual short story form. Robert Downey Jr.’s character takes faked photos of his girlfriend, as if brutally attacked: which are later mistakenly switched with another man’s photos of a real dead body, found in the river on a fishing trip. This stands as a fitting metaphor for the film’s accomplishment: we are unsure whether what we are seeing refers to an insulated, representation of violence against someone we know, or a dangerous and deep exposure to a real and universal horror. Sitting through these stories, we may feel both: that from this vision of Hollywood, there comes a both disconnected and hyper-connected image of humanity. We feel its ‘fakeness’, and: at the same time, its gripping reality.

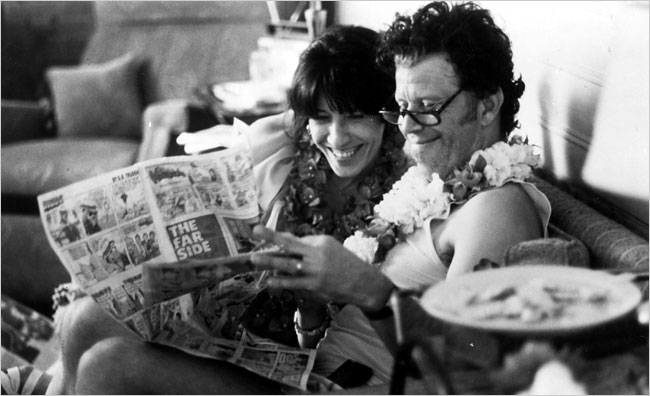

I couldn’t write this review without dedicating part of it to the inimitable Tom Waits, who appears as a cab driver (who wouldn’t want a cab ride with ‘the Devil’?) in one of the film’s first scenes. Short Cuts has many strong performances — from an accomplished cast — but Tom Waits is the perfect choice; a kind of musical and theatrical embodiment of the spirit of Raymond Carver himself. Waits plays the character of so many of his hauntingly beautiful songs: a hard-drinking, late night-working man of the (his) world. After a bust-up, Earl arrives the next day at the diner where Doreen (Lily Tomkins) works. ‘I’m getting us out of here, baby’, he tells her. ‘I’m getting us out of Downey.’ Later, back at their trailer, the two have drinks and food, and dance with fake Hawaiian lei’s to Waits’s crooning: ‘We’re getting out of Downey’. As the earthquake hits, they hope ‘it’s the big one’, to take them away together.

Elsewhere, the ‘quake offers a cover for a horrific act of violence, that we see from afar. Significantly, this — like the fishing trip that turns up a body — happens outside of the city, in a more ‘Carver-esque’ American landscape. Yet, ending here causes us to reflect: which of Carver’s stories – and which aspect of them — has Altman left us with? One of the things that cinema accomplishes is the safety of a distanced connectivity: the kind of humanistic connection that feels something like reality, but doesn’t leave people dead. In the television, we can play out a thousand lives and deaths, and live to tell the tale. Where this leaves us is a looming question, raised in Short Cuts and Carver’s oeuvre, behind it.

NEXT WEEK: Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist. For a more extended schedule, check in here.

Nice review, Andy. In 1993, the year Short Cuts was released, I was attending BYU and Short Cuts only played in one theater in Utah. I remember convincing a friend to skip class that day and drive with me to Salt Lake to catch a mid-week afternoon matinee.

Short Cuts is my favorite Robert Altman film. Structurally, it is similar (but superior) to Paul Haggis’s Crash, the Oscar Best Picture winner from 2004. (Kasdan’s Grand Canyon and P.T. Anderson’s Magnolia also come to mind.) All four films use multiple, intersecting story lines to weave together a kind of mosaic of some larger human theme (i.e. violence, racism, meaning of life, etc.).

I agree that Tom Waits is excellent in the film. He’s a character from Rain Dogs or Nighthawks at the Diner come to life. But I also really like the performance by another musician, Lyle Lovett, in the film. The scene where he bakes a cake for Andie MacDowell’s character is both touching and heartbreaking.

In my opinion, the only story that doesn’t quite work in the film is the Annie Ross/Lori Singer story, which, if memory serves, was the only story not originally penned by Raymond Carver.

That’s seriously cool to have skipped class for such a brilliant film. There are so many films that I would have loved to have travelled to see on opening weekend! :)

I’m a huge fan of Magnolia: in fact, thanks for reminding me about that one… I’ll go back and watch that again when I get a chance.

You’re right that the Annie Ross/Lori Singer narrative was an invention for the film. Perhaps the fact that it doesn’t seem to work is evidence that Altman’s idea of connectivity ultimately doesn’t succeed as much as the substance of Carver’s fragmented stories.

Magnolia is a frustrating film for me. At times it is so flat out Brilliant that it takes my breath away, or leaves me smiling from ear to ear. But other times it feels overwrought, overly melodramatic, or just overdone. During those scenes I feel myself pulling back and disengaging from the film. I still dig it despite its flaws. I just wish PTA would work more often. Only two films since Magnolia came out in 1999. Bummer.