This is a guest post by Mark B (aka, Mark Mighty And Strong) about an early Mormon feminist and her husband, who is the most effective Mormon missionary you’ve never heard of. Their names are Louisa and Addison Pratt.

We need to begin by clarifying that they are not related to the famous general authority Pratts, Orson and Parley P. We should also note that their marriage was complicated. But we are getting ahead of ourselves, so let’s start at the beginning, first with Addison.

He was born in New Hampshire, and at the age of 19 went to sea on a whaling vessel. For the next 8 years he sailed around the world, interrupted only by the time his boat put in at Honolulu to lay on supplies. Addison liked what he saw and jumped ship, taking up residence on the islands for six months and learning the language. His independent and adventuresome spirit would serve him well later in life, as we shall see. On a short stop at home, he met Louisa Barnes, who was a friend of his sister. They got married and began farming near Buffalo, NY. Louisa soon found out that the man she married was decidedly not a homebody, because Addison had a hard time leaving the nautical life behind. He would occasionally hire out as a captain on one of the freighter ships on Lake Erie. They eventually had four daughters, and when Louisa’s sister, a recent convert to Mormonism, told them that an American prophet was determined to build Zion on the western frontier, they became Mormons and left to join with the body of the saints.

They arrived in Nauvoo in 1941. Louisa soon saw the need for a school, and we get a good look at her character when we see that she went right ahead and established a school, without first seeking anybody’s permission. Both she and Addison had a way of being anxiously engaged, of seeing a need and filling it. In early 1843, Addison suggested to Joseph Smith that the Pacific Islands would be a fertile ground for missionary work, and on June 1, 1843, Addison and 3 companions left for the Sandwich Islands and Polynesia. Addison was the first Mormon missionary to teach the Restoration in a foreign language, the language he had learned as a young man when he went AWOL from his whaling ship.

He stayed there for five years and baptized over 3,000 converts. When we learn that he served four more productive missions, we realize that, as a missionary, Addison Pratt was a very heavy hitter. If Wilford Woodruff is the Babe Ruth of LDS proselyting, Addison Pratt is our Gehrig or DiMaggio. His name is on a men’s residence hall on the campus of BYU-Idaho, which I guess is the Mormon version of the Hall of Fame. He also had a Waldo-like ability to show up wherever the action was. He was present at Sutter’s mill in California when gold was discovered. He was in a party blazing a trail across the Sierra Nevada mountain range from west to east when they encountered what was left of the Donner party. He helped discover silver in southern Nevada, and was one of the original founders of San Bernadino, CA. It was on a short visit back in Salt Lake City in 1850 when Brigham Young “invited” Addison Pratt to take some plural wives. And Pratt declined the invitation. His audacious and independent spirit manifested itself again, as he concluded that polygamy was simply not an option for him. After that, he went on several more missions overseas and when he came home, he usually stopped in California, returning to Utah only rarely. It is possible that this was a deliberate effort on his part to stay off Brigham’s radar.

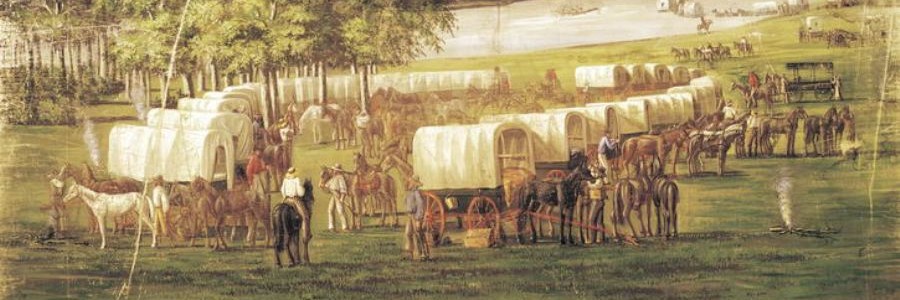

Let’s shift the narrative back to Louisa now. Her husband left in 1843 and she didn’t see him again until they met in Salt Lake City in 1848. This means she was on her own during the evacuation of Nauvoo, the slow, muddy move across Iowa, the long months of hunger and poverty at Winter Quarters, and the eventual move across the continent to the Great Basin. Her journal speaks for her, beginning with her reaction to the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum: “The women were assembled in groups, weeping and praying, some wishing terrible punishment on the murderers, others acknowledging the hand of God in the event. I could feel no anger or resentment. I felt the deepest humility before God. I thought continually of his words ‘Be still and know that I am God.'”

Let’s shift the narrative back to Louisa now. Her husband left in 1843 and she didn’t see him again until they met in Salt Lake City in 1848. This means she was on her own during the evacuation of Nauvoo, the slow, muddy move across Iowa, the long months of hunger and poverty at Winter Quarters, and the eventual move across the continent to the Great Basin. Her journal speaks for her, beginning with her reaction to the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum: “The women were assembled in groups, weeping and praying, some wishing terrible punishment on the murderers, others acknowledging the hand of God in the event. I could feel no anger or resentment. I felt the deepest humility before God. I thought continually of his words ‘Be still and know that I am God.'”

Louisa was the first literate, eloquent LDS woman to point out the sexism which is deeply embedded in Mormonism. Her journal gives us a good sense of her frustration with high-handed priesthood holders: “…those who had sent my husband to the ends of the earth did not call to inquire whether I could prepare myself for such a perilous journey.” But her courageous character prevailed and she recorded the answer she imagined her priesthood leaders would give her: “‘Sister Pratt, they expect you to be smart enough to go yourself without help, and even to assist others.’ The reply awakened in me a spirit of self-reliance. I replied, ‘Well, I will show them what I can do.'” She did just that, and prepared herself and her four daughters, and as they left Nauvoo she records that she felt “comparatively happy.”

We can only imagine what it was like for her to convert her family to the Great Salt Lake valley. In addition to the normal difficulties, she went as a single woman, with four daughters. It is not at all difficult to imagine that she was seen as a burden on the group, and that there were men who did not hesitate to “mansplain” to her how she was doing it all wrong. Again, her journal speaks for her:

“Last evening the ladies met to organize. Mrs. Isaac Chase was called to the chair. She was also appointed President by unanimous vote. Mrs. L. B. Pratt counselor and scribe. Several resolutions were adopted:. . ..If the men wish to hold control over the women, let them be on the alert. We believe in equal rights. Meeting adjourned.”

“Resolved, that when the brethren call on us to attend prayers, get engaged in conversation and forget what they called us for, that the sisters retire to some convenient place, pray by themselves and go about their business.” (I will confess that as I read her journal, I can feel myself falling in love with her, just a little, even from a distance of 170 years.)

In 1850, Addison was called on another mission to Tahiti. Louisa didn’t want to be separated from her husband again, so she sought and was given permission to go with him. In her typical way, she established a school while she was there.

Over time, Louisa gradually became convinced that plural marriage was an important part of the gospel, and this became a point of contention in the marriage. She moved back to Utah, and for the last decade of their lives, Addison and Louisa lived apart. They did not seek to divorce, and they continued to have a cordial and friendly relationship, sending letters and gifts and birthday greetings to one another.

The thing that I admire about both Louisa and Addison is that, in spite of the complicated messiness of their relationship with each other and with the institutional church, they maintained their sense of balance. Addison was able to look Brigham Young in the face, say “No” and mean it, then he just continued on doing what he did best — missionarying, trailblazing, exploring. And Louisa continued to see the admirable parts of the church and her husband even when they both let her down. They continued on with life, being anxiously engaged, without recrimination, hand-wringing, and bitterness, and managed to be, in Louisa’s words, “comparatively happy”. Their descendants include a chief justice of the Arizona supreme court and senator Gordon Smith of Oregon, as well as currently serving senator Mark Udall (D., Colorado).

Next time you are looking at a football team roster and see a name that is obviously both Polynesian and Mormon (Manti Te’o, anyone?), or the next time you hear a Mormon woman speak up for herself in a voice that is both authentic and firm, you are seeing the legacy of two of my favorite Mormons.

Very nice post.

Good stuff. Great running back insight too!

I love Louisa’s statement about her belief in equal rights, which I first read on a plaque near the Mississippi River in Nauvoo. Thank you for this more detailed account of her and her husband.

Lovely post. Great people.

Did her husband let her down? I think by standing by his principles (and against polygamy) he showed her more respect than many others showed when they accepted “the principle.” Thanks for all your trouble.

Angela, Ed,

Thank you!

CatherineWO,

This means that you and I have stood at the exact same spot! I love that series of plaques leading to the landing on the river. Heartbreaking, but also hopeful.

Just Another Reader,

I think it must have been a difficult marriage for Louisa, aside from the issue of polygamy, since he was just never around. But I think you bring up an interesting point, and somebody with access to primary sources and lots of free time needs to look into this issue of how 19th century Mormons handled differences when one spouse wanted to practice polygamy and the other didn’t. Oh, wait, I think I already have a pretty good idea how that was handled. :-)

Good article, very nice story. Is there a place where i can read her full journal?

Ditto to Travis’ request!

Travis/Tiffany,

As far as I know, her journal is available only on dead tree, not online. It is very interesting and full of interesting details.

http://www.amazon.com/Journal-Louisa-Barnes-Pratt/dp/B004MMW2SA/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1338432993&sr=8-1

Great post. I’ve added a quote from Louisa Pratt to my favorite quotes on facebook. Addison Pratt also seems like the kind of guy who would fit right into my family of nomads and thrill-seekers.

These two are my 5x great grandparents. I too admire and respect them. Thanks for this well written piece