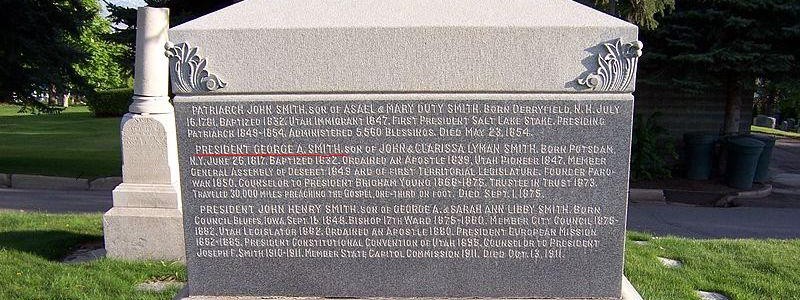

Generally, we’ll try to avoid showcasing General Authorities of the LDS Church as a part of this series, not because GAs are not our favorite Mormons, but because we like to celebrate lesser-known LDS figures, the rank and file members, the common Mormon. Today, however, I’d like to post about Elder George A. Smith, one of my favorite Latter-day Saints.

George A. Smith joined the LDS Church at the age of 15 in 1832 after reading the Book of Mormon. No doubt being Joseph Smith Jr.’s cousin played a not so small role in George’s conversion. Large for his age (eventually weighing in at 250 lbs, although only 5’10”), nephew George became one of Joseph Smith’s personal bodyguards. Brother George was also a member of Zion’s Camp, evidently not benefitting from the nepotism one would have expected when you consider he was officially out-fitted in clown-like, striped pantaloons made of feather ticking and he suffered from blisters caused by ill-fitting boots. No doubt due to some inspiration and some relation, George later became a Mormon apostle in 1839.

A British tourist once aptly described Elder Smith in the following verbal portrait:

“[A] huge, burly man, with a Friar Tuck joviality of paunch and visage, and a roll in his bright eye which, in some odd, undefined sort of way, suggested cakes and ale. He talked well, in a deep rolling voice, and with a dash of humour in his words and tone-he it was who irreverently but accurately likened the Tabernacle to a land turtle.”

Evidence of his good humor is found in his thousands (yes, thousands) of sermons and remarks. Said another one of his contemporaries:

“No one ever wearied of his preaching. [Elder Smith] was brief and interspersed his doctrinal and historical remarks with anecdotes most appropriate and timely in their application. Short prayers, short blessings, short sermons, full of spirit, was a happy distinction in the ministry of Geo. A. Smith.”

An example of his wry sense of humor is found in the following story Brother George once recounted while reminiscing about the wild days of early Kirtland.

“There was at this time in Kirtland, a society that . . .. not yet been instructed in relation to their duties. A false spirit entered into them, developing their singular, extravagant and wild ideas. They had a meeting at the farm, and . . . a revelator [named Pete, among others] . . .. manifested wonderful developments; they could see angels, and letters would come down from heaven, they said, and they would be put through wonderful unnatural distortions [such as barking, laughing and scooting around on the floor while “rowing in a boat to the Lamanites”]. Finally on one occasion . . . Pete got sight of one of those revelations carried by [an angel, and Pete started running after it] . . . and [he] ran off a steep wash bank twenty-five feet high, passed through a tree top into the Chagrin river beneath. He came out with a few scratches, and his ardor somewhat cooled.”

George A. also understood that brevity is the soul of wit, an unwritten gift of the spirit. As further evidence, here’s a legendary closing prayer given by him after a full day of conference meetings:

“Heavenly Father bless all good people, Thy servant George A. is tired. In the name of Jesus Christ, Amen.”

American Indians who were his friends (rather than those he fought in several skirmishes in Utah), knew him as “Non-choko-wicher.” Elder Smith wore a wig, glasses and false teeth, each of which he liked to remove in a kind of body-part strip tease-of-a-prank while in the presence of his Native American friends. “Non-choko-wicher” means “Man-Who-Takes-Himself-Apart.”

As much as I like sharing stories about George A. Smith’s wit and unpretentiousness today, I confess I’ve done so with some reservation. I’ve had to come to terms with and forgive him for–or at least withhold judgment about–the inflammatory rhetoric delivered by him from the pulpit at the time of the Utah War that likely contributed, if indirectly, to a horrific atrocity known to us as The Mountain Meadows Massacre. I’ve also had to forgive/overlook as well some personal views Elder Smith held that today we find offensive. I can only hope that any future chronicler who someday might be so desperate so as to consider my own words and deeds worthy of the annals of history, that she will likewise be as charitable to me in overlooking my many faults, focusing instead on the common humanity I share with her that might be noteworthy. And, if not noteworthy, I hope that like Brother George, at least my attempts at good humor and brevity, along with my attempts to discard my own personal facades, will permit an historian to withhold judgment and forgive me the many sins of my own generation.

Wonderful anecdotes and introduction to George A. Smith, plus I appreciate your nuanced ideas about what you’ve done re: his inflammatory rhetoric, etc. Nicely thought out!

Thanks, Ed. George A is Stuart’s great-great grandfather. My in-laws inherited one of his large rocking chairs–unfortunately, my mother-in-law got rid of it. In Nauvoo, his home was known for its large library. He and Sidney Rigdon were reputed for the size of their libraries–which explains the size of ours.

Cool Martine. Brigham Young once called George A. “a walking library.”

Love this, Ed!

Oh that we could all have a chronicler who is gracious with our faults, while still acknowledging that they exist, and while exploring our genuine human qualities in a way that makes others wish to have known them were it possible. Nicely done Ed.