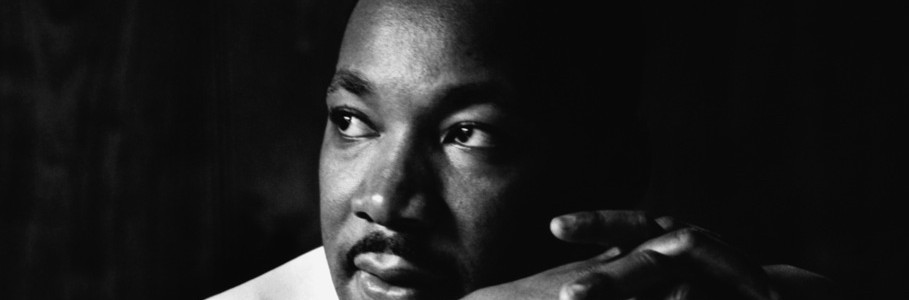

Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous April 1963 letter, written to his fellow southern clergymen, was not known to me, sadly, until I was a college student, some thirty plus years after it was written. But his words, true and powerful and shining as anything that came down from Sinai, made their mark on my mind as soon as the two were introduced.

By temperament, I am someone who desires harmony and agreement; tension is something I usually try to avoid. But I learned from Dr. King the power found in “a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth.”

He both wisely alluded to the rich tradition of American history and the stories of the Bible. I am especially struck by the power of his appeals to the Christian tradition throughout the letter. His mentions of Paul and Amos and Jesus himself (“Was not Jesus an extremist for love: ‘Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.’) paint a picture of these early church figures as proto-Civil Rights activists. The idea of one’s Christian beliefs being the driving force behind social justice activism was not something I had learned as a Mormon, but it changed my idea of what it meant to be a Christian.

Here are a few other of my especially beloved verses:

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.

For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

One may well ask: “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.”

One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty. I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.

Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

[T]ime itself is neutral; it can be used either destructively or constructively. More and more I feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than have the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right.

There can be no deep disappointment where there is not deep love.

If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century.

Beautiful.

This is so powerful, especially this quote:

“One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty. I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”

I despise groups today that take unlawful actions to further their cause and then they invariably plead insanity or some other defense in an effort to escape the demands of the law. Even if I might believe in their cause, I will never respect these groups. I will always respect King, Thoreau, Ghandi and others. It reminds me of certain Book of Mormon characters who laid down their weapons and accepted slaughter and thereby aroused the conscience of others.

The 5th verse was really great… “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?”

After i discovered your website I acquired therefore pleased, it’s the rainforest out there on the internet and there are 99 % bad websites without any content material as well as related information, but you go another way and provide us all studying within right here understanding of lots of good stuff!