Several years ago, in the midst of researching the process of canonization, or, how the Bible became what it is now, I started keeping track of texts and poems and essays that have been particularly meaningful to me. I started thinking of these writings as my own personal canon. I started asking other people about their own personal canons too, the stuff that sticks, the words we hang on to. And I’m still interested in what other people have collected in their own personal canons and I’m still trying to add to mine.

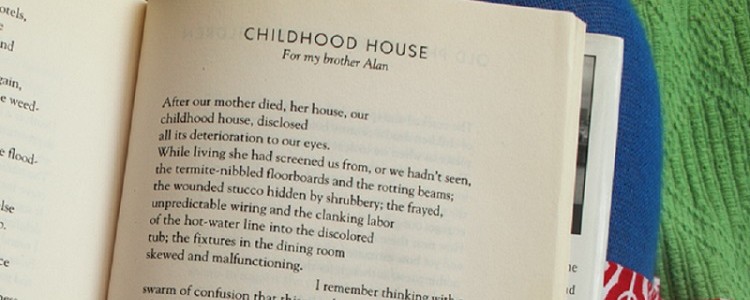

My research tells me that this poem “Childhood House” was published in the January 25, 1993 issue of The New Yorker. I cannot recall specifically when my childhood friend Carl sent me a copy of this poem, but send it he did and keep it I have. And with every passing year, the words become both more meaningful and more relatable. The words become more beautiful and more painful too. The poem speaks truth. It observes the way we remember and the way we forget.

My research tells me that this poem “Childhood House” was published in the January 25, 1993 issue of The New Yorker. I cannot recall specifically when my childhood friend Carl sent me a copy of this poem, but send it he did and keep it I have. And with every passing year, the words become both more meaningful and more relatable. The words become more beautiful and more painful too. The poem speaks truth. It observes the way we remember and the way we forget.

Ormsby writes in the second stanza of the poem, “Somehow I had assumed / that the past stood still, in perfected effigies of itself, / and that what we had once possessed remained our possession / forever, and that at least the past, our past, our child- / hood, waited, always available, at the touch of a nerve,” and I recognize my own assumptions in those of his, those of the poem’s speaker. I am a naturally nostalgic person. I save and hold on to and claim and savor all kinds of material and ethereal pieces of my past. On the shelves of my house, I display some of these treasures – a Fisher-Price Oscar the Grouch figure from the 1970s, a piece of birch bark from a tree that grows beside a cabin my family visited for a number of years, a piece of granite from Lake Superior, the broken bits of my baby teeth (I know?!), pieces of the Czechoslovakian china that belonged to my children’s great great grandmother, the 1963 sewing machine encased in a handsome mid-century table that was given to me by my children’s great grandmother, a pale blue gift card given to my parents when they married in 1971, a picture of my own childhood family in my childhood home, the five of us seated on the carpeted steps, and so on.

But the older I get, the less I remember. Many of the finer points of the memories I’ve been carting around for years have faded, the way the spines of some books I put on a shelf too close to south-facing windows faded. Bummer, as my books are organized by color. I’ve had to rearrange some of the most washed-out of the bunch.

Earlier this summer, I attended my 25th high school reunion. Part of the celebration included a tour of our school, which just so happens to be on the metaphorical chopping block. Our walk-through was underscored with the possibility that we might not be able to visit the school for our 30th reunion. Many of the rooms, nooks, and crannies I remembered. “Yeah, that was Boatz’s room, but who taught across the hall?” we said as we passed through third floor hallways. I found my senior English classroom and delighted in a stop off in our Orchestra room. The details were much as I had remembered them: orange lockers, painted tigers, cinder blocks everywhere.

Earlier this summer, I attended my 25th high school reunion. Part of the celebration included a tour of our school, which just so happens to be on the metaphorical chopping block. Our walk-through was underscored with the possibility that we might not be able to visit the school for our 30th reunion. Many of the rooms, nooks, and crannies I remembered. “Yeah, that was Boatz’s room, but who taught across the hall?” we said as we passed through third floor hallways. I found my senior English classroom and delighted in a stop off in our Orchestra room. The details were much as I had remembered them: orange lockers, painted tigers, cinder blocks everywhere.

But other places were a bit fuzzier. Some hallways appeared where they hadn’t been. Sure, honestly, who cares about hallways? But I didn’t love the sensation of not being able to remember things that I have previously been able to remember or discovering things of which I have no memory. My childhood Kara showed me a picture of something I wrote in her yearbook decades ago. But when I saw it, I didn’t recognize the words OR the handwriting, mostly because I like the way my handwriting looks now and didn’t want to claim that mess of an inscription. Of course, these moments of forgetting and reminding fuel small talk at a reunion event, so I’m not actually complaining. It’s fun to trot out versions of stories and compare them, each person spinning things in his or her own way. There is a certain warm security that comes with the telling of the old familiar stories. We each have our own collection of them and not unlike kids trading baseball cards, flipping through plastic sheaves to find so and so’s rookie year, we flip through our metaphorical sheaves and point out the details: a crazy haircut, a teacher’s temper tantrum, the time we watched the Twins play in the World Series in the cafeteria, the day the Challenger exploded, and so forth.

So just now, as I was writing, I texted Carl to find out when he sent me this poem. I wanted to pin the approximate date down and polish up the narrative. I wanted him to know how important this poem turned out to be. Thanks for sending it, all that.

“I have no recollection of the poem or poet!” he messaged back. “I don’t think that was me. [I]t rings no bell.”

Well. How perfectly fitting is it that in my memories about this stunning treatise on the fragility of memory I have made things up wholesale. I created a lovely story, but goodness, it’s a teeny work of fiction. I think that what must have happened is that years ago Carl sent me a poem from The New Yorker by Mark Strand. I kept that poem too. I have it taped to a bookshelf. And maybe I found this poem around the same time. I used to spend hours in the library as a college student reading back issues of The New Yorker and Rolling Stone. I have photocopies of old “Shouts and Murmurs” columns that I made for myself from the early 1990s. So I guess I made a copy of “Childhood House” for myself too. And then somehow I braided those two memories together.

Memory ” is not the intact garden we remember but, / instead, speeds away from us backwards terrifically”, the poem instructs. Sure enough, it does.

So what are we to do? I feel a little weepy and wobbly at the thought of all those memories speeding away. And a little defeated, although I recognize the joy that comes when we make memory recollection a group effort, when we all sit around on the deck talking about the old days or laugh with brand-new delight when someone reminds us of a detail forgotten.

I suppose all we can do is try to make memories worth remembering, even as we understand that every thing, even our thoughts, is impermanent.

Well, that and write at least some of it down…

Childhood House

by Eric Ormsby

;

After our mother died, her house, our

childhood house, disclosed

all its deterioration to our eyes.

While living she had screened us from, or we hadn’t seen,

the termite-nibbled floorboards and the rotting beams;

the wounded stucco hidden by shrubbery; the frayed,

unpredictable writing and the clanking labor

of the hot-water line into the discolored

rub; the fixtures in the dining room

skewed and malfunctioning.

I remember thinking with a

swarm of confusion that this was the true state

of our childhood now: this house of dilapidated girders

eaten away at the base. Somehow I had assumed

that the past stood still, in perfected effigies of itself,

and that what we had once possessed remained our possession

forever, and that at least the past, our past, our child-

hood, waited, always available, at the touch of a nerve,

did not deteriorate like the untended house of an

aging mother, but stood in pristine perfection, as in

our remembrance. I see that this isn’t so, that

memory decays like the rest, is unstable in its essence,

flits, occludes, is variable, sidesteps, bleeds away, eludes

all recovery; worse, is not what it seemed once, alters

unfairly, is not the intact garden we remember but,

instead, speeds away from us backwards terrifically

until when we pause to touch that sun-remembered

wall, the stones are friable, crack and sift down,

and we could cry at the swiftness of that velocity

if our astonished eyes had time.

;