This is a post about men. This is a post about women. No wait, this is a post about ‘men’.

This is a post about the relationships between women and men, ‘men’ and ‘women’: in a time of war. Of course, the work of feminism is far from finished, so writing about the role of men and their desire for understanding might seem a bit like the Germans trying to negotiate peace in, say, 1942. I acknowledge that my gender has committed both atrocities and oppression against women (not too-strong words), for many thousands of years. And, more, I acknowledge that I personally have both benefitted from and perpetuated that oppression in my own lifetime. I’ve lived more comfortably because I’m a man: and that makes me a collaborator, a perpetrator.

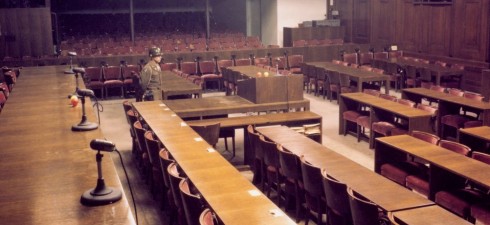

I am a man. I have been guilty of sexism, unconsciously and repeatedly. Men are in the dock: but what will be our sentence? Death and gender-oblivion? Or rehabilitation? Can ‘men’ (as a cultural construction) be re-made? This week, why talk about ‘men’, or ‘fathers’ at all? Why not discuss ‘people’ and ‘parents’, and work on emphasising our similarities?

I am a man. I have been guilty of sexism, unconsciously and repeatedly. Men are in the dock: but what will be our sentence? Death and gender-oblivion? Or rehabilitation? Can ‘men’ (as a cultural construction) be re-made? This week, why talk about ‘men’, or ‘fathers’ at all? Why not discuss ‘people’ and ‘parents’, and work on emphasising our similarities?

Well, for one, because everyone born with XY chromosomes still inherits a privileged position in our culture and society: a cultural institution of ‘maleness’. It’s a familiar situation here on D&S: we find ourselves wondering whether damaging cultural institutions are best dismantled, or re-fitted, to function in new and more egalitarian ways. I believe that if more enlightened men simply abandon ship on conceptions like ‘masculinity’, then they leave the boat to those who would capitalise on its worst effects. No, rather, we should work to redefine the institution, to leave a better world for our children: where the cultural connections from ‘being a man’ will foster understanding about what was wrong with the old way, and a new, absolutely equal conception of gender difference.

How should we go about this? First, get the science. My wife Helen recently read an excellent book that debunked a lot of the cultural myths surrounding how much gender really affects the brain and body. As it turns out, it’s a lot less than even the more liberal-minded of us might think — we construct stories that turn the few differences into supposed ‘abilities’ and disabilities. When we better understand really how slight the gap is between men and women, we won’t overstate or make excuses based on these myths. We’ll see that we’re free to remake ‘male-ness’ and ‘female-ness’, because gender really is as open to self-definition as our humanity.

Second, redefine the family. It’s been big news in recent years that there’s a battle going on between those who consider the ‘traditional’ marriage to be only between one man and one woman, and those who would widen this definition. This shows an interesting cultural shift, however, from a time where the liberal left had simply abandoned marriage as an outdated and hegemonic institution. Now, groups across the spectrum understand the power of marriage, and want to remake it into something egalitarian and reflecting the progressive values of our age. The self-definition of gays and lesbians do not erase gender differences: however, their rejection of the rigidity of the old gender roles within marriage is inspirational for heterosexual couples, moving to redefine their own marriage institution. (Perhaps the greater number of categories in ‘LGBT’ is a good model for moving away from the binary?) Yes, we should all learn from the ‘gay marriage’ debate: ‘traditional marriage’ is obsolete. The days of the patriarch and home-maker are gone. We need new, flexible roles, which don’t erase or prescribe based on gender.

Third, re-work the workplace. As we’ve worked for greater equality in our family, Helen and I have come up against a significant external barrier to redefinition of our roles: our society significantly favours specialisation in the labour market. A couple who both share in the parenting equally will be unlikely to be able to work 40 hours per week each. Many careers require even more time in the workplace than this — an exhausting prospect, without outside help. Modern families face a choice: either to not have children, to specialise to some extent (one person to have a career, the other to primarily take care of kids), to accept financial and professional disadvantage, or risk exhaustion/share much less time together. Our economic system is based around the principle of specialisation of labour, so I can see that there’s a lot of history that goes into promoting that approach. Can we move beyond this, to a world where we believe that diversity of work can foster a better quality (and sufficient quantity) of output?

These challenges, and doubtless many more, are the responsibility of men and women in our society. To not be aware of the issues raised by feminist theory and activism is to live with your head in the sand: but to be aware, and not act to redefine the culture, is betrayal of half of our species. In order to overcome these challenges, we need not men and women who ‘abandon ship’ on the recognisable terms: but men and women who accept and demand a reworking of their respective cultural-historical institutions. The title of the ‘feminist’ movement has suggested a power struggle: a movement of power in the direction of XX chromosomes. For sure, this movement still needs to take place — but so much more. ‘Mature Masculinity’ will be about a remaking on both sides and between: re-made institutions, reconstructed traditions, and renewed relationships.

Excellent post. Family-life in the post-modern world will be very different from the 1950s model we idealize. I hope the young people involved will have a voice in creating an economic system that allows both parents to nurture. Since old people have the power, I am less than optimistic.

Great post Andy, I appreciate your your comment on seeing marriage in broader terms rather than just giving up on it. Discussions on gender that include marriage too often fall into diametrically opposed camps, when there is increasingly a spectrum of marriage experiences.

I do, however, refuse to feel guilty for being a male. To hijack a Lady Gaga theme, I was born this way. Repression of women is wrong and despicable, but the best way to combat that is to live a better way. I don’t think we are punished for Adam’s (or any other ancestor’s) transgressions.

Thanks Colin. I absolutely agree that we shouldn’t feel guilty for being male (ie. XY chromosome): there’s nothing to feel bad about with that, per se.

I do take my title, and the initial verdict of ‘guilty’ from my personal feeling that I’ve both benefited unfairly from my willingness to act through the advantage of my status as a ‘man’ (cultural construction), and my unconscious sexism that I’ve expressed through language, action and complacency. I believe that with greater diligence, I could have done better. I think most men are in the same situation as I am. I see it in similar terms to buying goods from a company that exploit workers, or supporting a regime that commits atrocities. It’s not always direct or conscious ‘transgression’, but nevertheless, my hands are bloody.

Therefore, in the future, where the culture will not fairly advantage us, and we will be more widely educated on these issues, we will have less reason to feel the guilt of our status and situation.

BTW, love Lady Gaga.

Andy, what a great post. You are so clear about WHY we need to rethink gender roles, which is a concept lost on many people who don’t already consider themselves “feminists” or “progressive” or “liberal”. And I think your ideas for change are spot on!

Now that’s what I call ‘mature masculinity’!

GREAT post, Andy! I especially like your thoughts on re-working the work place. I have thought about this so many times because I still believe that kids need parents who can be there for them a lot of the time. The way things are set up now, one of the parents has to sacrifice. My cousin is a nurse and her husband a pilot. They seem to have struck the gold mine on careers that allow for co-parenting and I really love seeing them in action. What a great example they are to their children. Is this a discussion happening in other places? Do you see this type of change in our near or even distant future?

Ashley, I don’t know if you saw my review of a book by Rebecca Asher who talks all about changing to a world where shared parenting could be a reality.. also, I have just started following the Equally Shared Parenting blog.. I really think this is the way forward.

Excellent stuff Andy. I have personally seen how 2 can lead to 3. A gay co-worker of mine recently adopted two babies with his husband. Contrary to our firm’s culture and unwritten practice, he took the full paternatity leave and made some other changes. Whereas this is common for female employees, it is not for men. It shoudn’t matter, but for some reason his situation—-be it his orientation, the fact that his spouse is a male, or his bravery/experience in pushing cultural boundaries, I don’t know—allowed him to do this. My sense is that he has in fact inspired other men and opened some doors.

I do not want to betray half the species, to say nothing of the women in my life. The specialization barrier you reference in 3 is so very problematic. But even harder are the walls in my mind–thanks for the reminder.

I love the cartoon btw.

Great, great suggestions, Andy! I really liked your insights about the workplace as well. I think it’s honest and not sexist to say it will be very difficult to rear young children while both parents work demanding jobs. This is not to say it can’t be done, only that arrangements have to be negotiated and discussed honestly and fairly instead of just defaulting to the societal status quo.

I love the final phrase too – grappling with these issues really does promise a wonderful pay off if we can get it right, both halves of the species!

I so needed this on a day when I almost walked out of Relief Society. Our lesson was on the eternal blessings of marriage, and our 80+ year old teacher reminded us women that our husbands were the head of the home, they were the spiritual leader, and they were the final say in all decisions. Well, I couldn’t just let that go. I asked why I can’t ask my own child in my own home to say a prayer. How can I be an equal partner to my husband if he’s in charge? And a whole bunch of women commented reinforcing the patriarchal model of marriage. I kept my mouth shut the rest of the lesson, but came home in tears never wanting to return. I’m sure I’m the ward pariah now. It’s good to be reminded that not every Mormon out there believes in a 1950s version of marriage and family life. I’m just not sure how much longer I can live with the cognitive dissonance.

“The days of the patriarch and home-maker are gone. We need new, flexible roles, which don’t erase or prescribe based on gender.” My absolute favorite part of this essay.

Thanks Risa! I really needed your comment, too, on a day when I wondered whether I have anything more to give writing on this blog. It makes such a difference to know that something I have written might have helped you, all the way on the other side of the world. We are brought close together as a community, through our shared feelings and good desires. I know just how you felt in that lesson!

Argh, Risa. I’ve had so many Sundays like that. I feel your pain.

I like Andy’s post because it feels hopeful.

Very nicely put. I happen to have a husband who hates the term “feminism” and I can understand why… the term itself lends toward the assumption that it is all about the feminine… and not about bettering life for all of us. I like your term “Mature Masculinity” as well for an offset for the term “feminist”… however I really wish I could find a term that would encompass both but also have with it the strength of my conviction in my need for a cultural reconstruction of societal gender constructs.

I have been too busy to read blog posts the past couple of weeks, but my daughter emailed me with a link to this one, telling me I had to read it. I’m so glad I did. Thank you. I agree with you 100%.