As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that most things are complicated.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that most things are complicated.

For example, social systems are made up of mostly rational (or at least aspirationally-rational) folks. It doesn’t matter how crazy things are in aggregate, the individuals involved are almost always remarkably normal. Take footbinding (I’ve written about it here). Were the mothers that hobbled their daughters sadistic psychopaths? Nope. Just normal moms faced with a really shitty decision-set.

Here’s what’s interesting, though. Although the mothers that did this to their daughters didn’t intend harm, the institution of footbinding was harmful (and by the institution, I mean the normative, self-reinforcing social structure that perpetuated it for generations). It was almost impossible to stop. It took a hundred years and the combined efforts of Western missionaries, feminists, and the full weight of a ruthless communist regime to end it.

Compared to footbinding (and things like genital mutilation, female circumcision, etc.), LDS women have it pretty good. So why do some Mormon women want the priesthood? Don’t these women understand that God set up the church this way? It’s a divinely inspired division of labor. Separate but equal (as Brother Jake explains in this YouTube video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yELRN8cx1Dg). So what’s all the fuss about, exactly?

Good question. This is what all the fuss is about: http://www.ldswave.org/?p=402. It’s about women saying “I feel unequal when. . . .” It’s about having moments when you see the church as “half a church.”

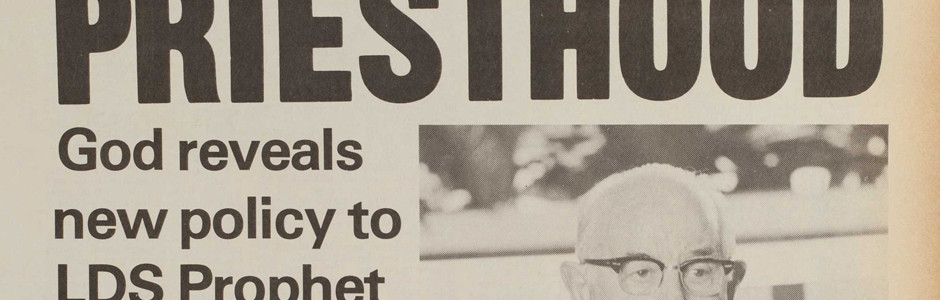

Before we talk about women, though, let’s talk for a second about other “institutions” in the church. According to the Book of Mormon Musical, “in 1978 God changed his mind about black people.” I’m not sure about that. I can’t find any evidence he didn’t like blacks before 1978. I can’t find a single revelation (or even a legitimate claim of a revelation) banning blacks from the priesthood (or the temple). So how did it start? Why was it perpetuated? All I can see in the ambiguity of history are assumptions, norms, and an ugly self-reinforcing system of discrimination that we accepted as the way things were supposed to be. Spencer W. Kimball, it is reported, (http://www.the-exponent.com/what-can-we-see-from-the-mountaintop/), didn’t ask God to hand him a script or give him new marching orders as much as he pled with God to help him see past his own assumptions and prejudices. In other words, he went to God and asked for the blessing of being able to imagine things differently. Think about that for a second.

On a more cynical note, in the case of blacks and the priesthood, what does it say about us (as individuals, and as a church) that we needed God to pull us out of a pit we apparently dug for ourselves?

In general, if we don’t like the outcomes a social system produces, what then? That’s a great question. For some, the best course of action might be acquiescence. Yes, acquiescence. Acceptance and the daily struggle of making the best of things, in some cases, is both noble and courageous. For others, it may be subtle efforts to push for incremental change from the inside, or respectful protest, or having the courage to leave (if that’s possible). Others may gather in the dead of night with torches and gas cans, intent on lighting something on fire.

In general, if we don’t like the outcomes a social system produces, what then? That’s a great question. For some, the best course of action might be acquiescence. Yes, acquiescence. Acceptance and the daily struggle of making the best of things, in some cases, is both noble and courageous. For others, it may be subtle efforts to push for incremental change from the inside, or respectful protest, or having the courage to leave (if that’s possible). Others may gather in the dead of night with torches and gas cans, intent on lighting something on fire.

Regardless of how approached, social change is hard. We don’t need to make it harder by pretending our own approach is superior. We need to let ourselves be inspired by the efforts of others, even when those efforts are different than our own.

Specifically, when it comes to the question of women and priesthood, what should we do? I don’t have a good answer (or at least I don’t claim to have the answer). Here are three things we shouldn’t do, though (or allow our leaders to do):

1) We shouldn’t equate biology with institutional authority.

Imagine walking into the chapel on a Sunday morning. You look up on the stand and see three women (the bishop and her two counselors). You see 10 or 12 young women getting ready to bless and pass the sacrament. You pick up a conference issue of the Ensign as you sit down in the pew and notice that all the top leaders of the church are women. After a few minutes on your smart phone, you conclude that nearly all the top managers and board members of different church entities, both for-profit and non-profit, are women. As you ponder this reality, your twelve-year-old son sitting next to you tugs on your sleeve and asks “Why are women in charge of everything at church?” You pat him on the head and remind him that one day, his body will be able to produce sperm, and that he’ll have the sacred privilege of being a father. “Women can’t do either of those things,” you remind him. “So you see,” you explain, “sperm production (and fatherhood) is what men get; being in charge of everything is what women get.” Different, but equal (as Brother Jake explains).

2) We shouldn’t equate value with institutional authority.

Ponder this. In the South in the 1800s, slaves were valuable. The economy couldn’t have run without them. They were not, however, equal. When women complain about feeling powerless (or marginalized, or invisible, or disrespected, or not taken seriously, or exploited, or overlooked), being told they’re “valuable” is part of the problem.

3) We shouldn’t pretend it’s not a problem.

In a public forum, a women recently recounted an experience she had in her ward a few years ago. She had worked for several months preparing a number of piano pieces for a recital as part of her Personal Progress project. She had been led to believe that her achievements were roughly the equivalent of an Eagle Scout award for males. She planned, sent out invitations, and anticipated the same level of enthusiasm from adults as she’d seen for her older brothers and their friends when they completed their Eagles. When three people showed up to the recital, and the bishop forgot to mention her achievement in sacrament meeting the following Sunday, she learned a hard lesson about the realities of patriarchy.

Another woman in a similar forum recounted the struggles of being a single mom. Her son was 16 and had just received the priesthood. Her daughter had just turned 8 and was about to be baptized. Because she couldn’t play any formal role in the baptism, she reconciled herself to the notion that her son could baptize his sister. During the baptism, when it came down to move to the font, her son had trouble unlocking the door to get into the font. She left the room, unlocked the door, and by the time she got back, the baptism had been completed. No one had missed her or thought to check if she were in the room.

Yesterday I was in a FB discussion with a woman who does, I suspect, a fantastic job of magnifying her calling as the Activity Days leader for girls ages 8-11 in her ward. She recalled going to Goodwill to buy used tablecloths to cut up and sew boy-scout-like sashes for the girls and then making homemade pins and other awards for the girls to put on their sashes as they completed different projects. She was responsible for nearly 20 girls. Even though they met twice a month, she operated on a shoe-string budget of $100 dollars for the year. She did it without complaint, often spending her own money. This leader had just found out, however, that the boy’s scouting budget (excluding funds from an authorized fundraiser) for the same time period for half the number of boys was $1500.00.

Once you become aware of the problem, you see it everywhere. It’s cultural. It’s systemic. It’s grounded firmly in biases, faulty assumptions, and, fundamentally, in a lack of imagination. So many of us, both men and women, simply can’t imagine that things could be any other way. Elder Ballard recently gave a talk titled, ironically, “Let Us Think Straight” (http://speeches.byu.edu/?act=viewitem&id=2133). Unfortunately, the talk not only fails to live up to its title, it’s embarrassingly unimaginative.

Here’s why women need the priesthood:

“It’s because every time I’m on a plane, and the captain’s voice on the intercom is female, I get a little teary. I’ve never wanted to be a pilot, and it really doesn’t make any practical difference whether a man or a woman lands the plane safely. I have no eloquent or reasoned argument to explain my emotion. But it matters. It. Just. Does.

I want my daughter to know girls can fly.”

[Posted on By Common Consent (by Kristine): http://bycommonconsent.com/2013/01/15/why-id-like-to-hear-a-woman-pray-in-conference/]

[For a continuation, of sorts, of this discussion, see this post: https://dovesandserpents.org/2013/09/women-priesthood-cookie-jar/]

Yes, girls need to know they can fly – instead of finding that out at age 54 after long and hard struggles like

I did. Beautiful article Brent. You get it. Thanks.

“we needed God to pull us out of a pit we apparently dug for ourselves? ”

EX-AC-TLY!!!!!!!!!!!

good article. I just finished reading Denver Snuffers book “Passing the Heavenly Gift” which addresses several of these topics. Denver’s book provides clarity why we have strayed so far from the Church/ Organization our dear Prophet Joseph Smith started.

“why we have strayed so far from the Church/ Organization our dear Prophet Joseph Smith started”

Umm, if we didn’t need any more prophets, why do we need continuing revelation? The polygamists, for one, are generally locked up it this mindset of keeping it at Joseph Smith’s day. If Joseph Smith is what we think he is, he certainly sees all of what’s going on, and certainly honors the current prophet and not only most certainly honors that role, but sustains it, since he has both an understanding of it, and a more, shall we say, eternal perspective on it, considering that he’s on the other side of the veil, as we say?

There’s one more consideration in the reasons for prejudice, other than the ability to imagine things outside cultural norms. it’s fear. it’s a very real fear for men that if women are allowed equal opportunity, it diminishes their own. In observable practice, women tend to be more dedicated, effective, and motivated than men when allowed to take part in institutions historically dominated by men. See the number of women attending colleges compared to men – its a significant majority women – and so likewise positions in industry as ceo’s and leaders. It’s deeply frightening to imagine those you’ve been prejudiced against for so long gaining the same ability to be prejudiced against you, and many men are afraid.

Saaay whaaaat? You’re saying that the Quorum of the Twelve and the First Presidency are prejudiced and unable to imagine things outside of cultural norms? These are the guys (as well as the general auxiliary presidencies) who travel the world and meet all cultures, and also have learned to quench their own thoughts and feelings when the Spirit directs them, which is on a level much closer to the Lord than most of us can even imagine. While they may have strong feelings about things, being attentive to the Spirit is their full-time job.

Perhaps, and I hope this is what your talking about, is that in the general body of men in the church, that there are fear and prejudice to things that are new. Well, probably about the same as in other groups, right? Hopefully less so, because one of the things taught in the Gospel is how all are our brothers and sisters. However, this body of men will follow the prophet (by and large) in whatever direction he takes the church. How quickly was pride swallowed (when and where it exists) after the 1978 revelation? Probably pretty quickly.

While your statement might make a good, “impactful” press, isn’t it more of a supposition on your part?

It is clear historically and linguistically that men feel disempowered whenever women get an equal share of whatever. When I hear men say and women recite that men would be devalued if women had the priesthood it makes my blood boil. It is a throw-back to men believing they are better. Don’t patronize me with ” oh we’re not better just different”. Hogwash ! If a woman can have something that has been exclusively male– of the males, for the males, and by the males so help us God–(who conveniently enough for men they get to be the ones to say what God wants! How fortuitous !) then men don’t want it any more because it has now been tainted by women. If women were equal in all eyes then men would be proud to share. Instead they are insulted. When historically have men ever wanted or even cared about anything women held exclusively. I submit NOTHING. Because it is without power, clout, control or credibility. go On chanting your crazy talk. An deep hoping that this organized superstition makes any difference. If the priesthood were that powerful SLC would be famous for people getting well. Once diagnosed with any given disease Mormons die at the same rate as anyone in the general population.

It’s unfortunate that all you think this is about is power. If you actually understood the priesthood, and the task of leadership in the church (or accepted what had been related about it), it’s certainly not about “who’s in charge” because every leader (generally) learns that the Savior is very much present, and in charge. The Savior is palpably sensed to be in charge for so many priesthood leaders (and auxiliary leaders) that I know. For all leaders, the question is either to interfere with the Spirit, or to stay out of the way of the Spirit and it its influence produce miracles in lives, families, and congregations. The interfering with the Spirit leads to unhappiness and distress, and even reprimand (being reprimanded by the Spirit is not a pleasant experience).

It’s troubling to hear of a member whose experiences does not lead them to understand what leadership (as experienced by leaders) is about in the church. Rather, the troubles are about what it seems to look like.

Terrific. Cogently written. Thanks.

If any one knows anything about the Priesthood is that women actually wield the Priesthood through their husbands. Women keep their husbands grounded and even though he has the authority she can use it. She is equal in all respects. Without a women, Adam would still be walking around in the Garden of Eden, oblivious. The Lord picks Prophets and leaders, not man. Wants man starts to say who gets what, that is when Satan has truly won.

“A wife does not hold the priesthood in connection with her husband…”

Joseph Fielding Smith, 1907

Joseph Fielding was wrong. My wife gave our dead baby a blessing when I wasn’t there and brought her back to life. Now I include her in all blessings, she has as much power in her priesthood as I do in mine. She was endowed with power (in the eyes of God) is allowed to function in any Melchizedek priesthood capacity. Her endowment used the same words as mine and was received “preparatory to officiating in the ordinances of the Melchizedek Priesthood”

In the church, men do say who gets what, and only men, which is the point of having discussions like this. Though I reject your conclusion that therefore Satan has truly won because, again, we’re having discussions like this. I also completely reject as unscriptural and undoctrinal your characterization of men as spiritually inferior to women. It’s just more sexist nonsense, clothed in the thin robes of false humility. And as a man and a priesthood holder, it’s also not my personal experience. So speak for yourself.

Why do so many Mormon men believe that degrading their own spirituality somehow empowers Mormon women?

It’s NOT only men! Most priesthood leaders (if not all) consult with their wives. And women ARE involved in big decisions. (Relief Society president, young womens president, primary president, etc.) . Funny enough: Ask most ward councils who has more say: The young womens president, or young mens president, and I can guarantee that most will admit wholeheartedly that the young women’s president does. True story.

Those who are looking for ugly aspects will always find them. In this case, I think many people are looking for problems, and making over-generalizations to justify their feelings.

Assuming you are even being serious (please tell me you’re not), you are completely wrong and your stereotyping is offensive. I’ve served in three bishoprics, and unless you’ve served in four or more, I’ll claim at least as much authority as you to make universal statements about the points you raise. Callings are not shared, and both personal and ward affairs discussed in BM, PEC, and WC are considered private and proprietary to the ward leaders ordained to the relevant stewardships. Discussing these matters with your spouse or anyone else is just gossiping. To be very clear here, consulting with your spouse about priesthood leadership decisions is not permitted, countenanced, an “unwritten order,” etc. Everyone at every level of leadership knows this, or should, but admittedly some don’t get it. Which is one reason why sensitive matters (following the handbook btw) are rarely raised in WC. And most bishoprics are very conservative in what they judge sensitive.

And in the several hundred ward council mtgs I’ve attended, women have always been modest and non-voluble participants. In any case, ward council meets once a month, usually for just an hour, and is not where executive decisions are made. That would be in bishopric meeting (mostly) and priesthood executive committee. BM alone is often 3+ hours/wk (usually Sunday morning and a one weeknight). Are you really suggesting that the bishopric runs the ward from a 1hr/mo meeting dominated by talkative women? Who’s making absurd over-generalizations to justify their feelings?

What “stereotyping” are you referring to as offensive? I am genuinely confused. I said that women are consulted and involved. How is that a stereotype or offensive? You don’t want me to give women the credit they deserve in being allowed to express opinions and counsel? We’re not talking about sensitive issues that are confidential. Completely different matter. (confidential info stays confidential, just as if a sister approached the Relief Society president for individual private counsel = THAT wouldn’t necessarily need to go further either). A member of the seventy told us point blank in a meeting, that priesthood leaders could and should counsel with their wives in regards to callings and other such things,. It is NOT gossip (that is an offensive stereotyping), since the husband/ wife discussion does not go to other ears. They provide counsel and support of EACH OTHER in their prospective callings. If they shared their discussions with others, then yes, it would be gossip, which is not what I eluded or even hinted at.

And where did I say that the ward was run in a one hour monthly meeting by talkative women?! LOL. Nothing I said had any reference to that crazy statement.

Obviously, you have some very strong feelings. I don’t understand where this is coming from or what exactly you’re getting at.

I am truly sorry that you have obviously been offended by something.

I guess I was just trying to say that even with staying in the confines that the church handbook has set and advised, and following counsel given us by local and general authorities, I feel that as a woman I DO have a voice in the church. I have had my counsel listened to, and even when it was not used or implemented, it has never bothered me, because I still felt listened to and valued. I guess in the 20+ wards I have been in, I have been very fortunate to have great leaders (both male and female), who understood Christlike leadership and led in a way that invited in the Spirit.

I am very sorry you have felt contention, and by misconstruing my words now feel contention towards me. I do apologize. I was not meaning malice, but rather was trying to validate MY personal feelings of worth.

P.S. per the handbook, the bishop IS supposed to meet with auxiliary presidents in private meetings once a month (in addition to wc).

I apologize. You made some concise statements that I probably misunderstood, and if my response does apply to your viewpoint, please ignore it. Yes, I was offended. You responded to my post by disagreeing and then said, “Those who are looking for ugly aspects will always find them” and that many are just “looking for problems.” I read that as a character judgment from someone who does not even know me.

The stereotyping I referenced was your suggestion that women verbally (and perhaps otherwise) dominate men in leadership settings. This is one common argument against women’s ordination. Men are too unassertive and unmotivated to be equal partners with women in leading the church; they would just let women do it all, if given the chance. Priesthood and its leadership responsibilities are necessary to “push” men spiritually; women, being more spiritual, do not need that push. My wounded male pride rejects every hint or species of that argument. I believe men and women are spiritual equals, without qualification. And in my experience, women are not verbally or in any other way dominant in church leadership settings. More often, if anything, they may be somewhat cowed by their minority representation and non-priesthood status.

The seventy who said that “priesthood leaders could and should counsel with their wives in regards to callings and other such things,” which I would characterize as matters of revelation and stewardship, was either misunderstood or is boldly contradicting church teaching and policy. Though in the latter case, I really respect him for trying to address in some way the church’s gendered leadership gap, and would love to know who it was. I’ve never personally heard this is any priesthood leadership training meeting, etc.

But at least in our official doctrine and policy, spouses do not jointly hold the keys to revelation for their respective callings or otherwise serve as shadow counselors to church leaders. For me to discuss with my wife how much budget we should give the YW program vs. scouts, whether Sis. Jones or Sis. Johnson should be RS president, or any similar bishopric matter really is (officially) inappropriate. I’ve never seen a spouse’s counsel raised for consideration in a bishopric decision, though I think you agree that would be very wrong. I think you are saying that counsel given by a spouse to a church leader should be “ears only” and silently mediated into leadership decisions. But for me that would imply that revelation for our callings comes both directly through the spirit and through our spouses, or that, e.g., a bishop’s unofficial first counselor should be his wife. I personally accept the merit of considering that, so on this level we may completely agree. (Though you may not go as far as I would.) But that is not the doctrine, policy or the order of the church and, I think, rare in practice.

Thank you for your apology, though I know now that I made a false assumption which makes me the only possible offending party here. I did not know you were an LDS woman who was trying to explain or, as you bravely say, even validate her feelings of self-worth within the church. There is no reason for any LDS woman who is happy and fulfilled, and feels personally empowered within the church, to experience the distress of others over this matter as a personal critique or blame. I know we share the same goal here; for every woman in the church to feel the same joy, belonging and empowerment as you do. Achieving that will take discussion and is worth risking misunderstanding. Distress for my suffering sisters affects my tone, but that’s no excuse. I apologize for being uncivil.

Gah! That is, “if my response does *not* apply to your viewpoint, please ignore it.”

My wounded male pride – Thank you for your comments. I really do appreciate them and think you said it very eloquently.

I agree totally. I like your comments and your perspective here. Consultation with wives is big time with bishops. Certainly not about the confidential stuff though, but more like background information on things and people and families, and their perspectives, and certainly trying not to tip their hands as to what it’s about (if it might be about a future calling or some such). Wives are a conduit into the workings of the ward through a different route than men have and they have a different perspective. Wise bishops (and there are many of them) consider these things. It goes with the turf, I suppose. It also goes the other way, too. My brain was picked at times by wife, and when I couldn’t comment (because of lingering confidentiality issues, though I never mentioned that), I said so. I was certainly directed by the Spirit to never interfere with my wife’s calling, and she never was nosy or interfered in mine.

Having said this, I do have to say that if someone had come to me for counsel (generally spiritual in nature) about an issue, and after I had given my response had then asked, “What does your wife think?”, besides thinking it was really off, I would likely have said, “Why don’t you ask her yourself?” and gone about my business, but I wouldn’t have let them see me shake my head in puzzlement.

I can’t say enough about how I love the RS presidents! Their input was not just valuable, but essential, as were the YW and Primary presidents.

I’m pretty sure he meant if man, as in the human race, is saying who gets what, rather than receiving and trusting in revelation from God, then Satan wins. And if that wasn’t what he was saying, then I am. What this article and many comments are missing is faith. If you are questioning God, good luck with that. He only gave us everything we have, so why not try to say His way is wrong?

Power or authority that I get only through my husband is no power or authority to me. Because I need him for it.

I am autonomous. Yes, I am married, but my spirituality and my participation in my religious life need not be predicated upon my husband. I reject that premise outright.

Then you obviously don’t understand it. You need a husband to be in a celestial marriage too. . . . Does that bother you? I’m curious how many complaining about this have real experience. Every bishop’s wife I’ve known has been his greatest counselor and would NEVER wish for his job. As a wife of a man who has been in several bishoprics, I know that I am the first person he consults about most issues. We are equal partners and a team in every aspect. He doesn’t begrudge the things he needs me for, and I don’t begrudge the things i need him for. I LOVE my marriage and that it IS interdependent. IF you are not dependent on the other person, then what kind of marriage do you really have? BTW- I am a military spouse, and have had to be separated from my husband many many times, and yet we still keep our interdependence despite the need to be completely independent. I seriously feel sorry that you don’t understand the beautiful aspects of interdependence.

LKB — excellent points

There’s a LOT more to priesthood service than serving in a bishopric or other administrative calling. Not everyone who desires ordination desires to be Bishop (or Stake Clerk or Sunday School President or Executive Secretary). Same as how not everyone who HOLDS the priesthood wants to be bishop (or stake clerk or SS president or Exec Secretary).

Reducing ordination to the ability to lead a congregation or an auxiliary is a diminution of the gift God has bestowed on men in the church, and those who cannot see beyond the titles and mantles of service are missing out on a big part of what priesthood is, can, and should be.

I think also gets back to the difference between priesthood ordination or priesthood power, as elaborated so well by Sis. Burton (and others). When leaders speak about living up to our privileges, or keeping our covenants, it’s about what’s been bestowed on us through and pretty much left up to us fulfill. Passing sacrament is one thing, but enabling the Atonement in our lives, and being able to remember the Savior through covenant and having His Spirit to be with us is the greater thing.

While I enjoyed the preamble up to the three points, the three points puzzle me.

Last first: #3: that’s not about anything doctrinal, it’s about human failures. For the budget, which are tight, the appropriate thing to do is to speak up — the squeaky wheel gets the oil. If the allocations are only about tradition, there’s a problem, but most bishop are pretty practically-minded, as are other leaders. Unfortunately, I’m not sure how many wards actually look at the budgets these days. For the baptism, what a goof. Leaders should know that it’s about families and those who are important to the recipient. But goofs happen. If leaders don’t listen, if members don’t listen, either way, not listening to the counsel and instruction that have been given has results, usually some unhappiness (at varying levels), as witnessed. The piano recital — embarrassing. That might also be ward tradition. But certainly not anything about priesthood. So this would change if women “had the priesthood”? Really? What’s the connection?

#2: Are the two the same? Slavery and women not holding the priesthood? Reducing the reasons to this level (basically of tradition, like the foot-binding) leaves out revelation. The patterns of the priesthood? Well, for one, in any priesthood lineage, which goes back to Peter, James and John, it is noted that Christ ordained them to the priesthood. Was this because the existing society was sexist, or because it was the way He wanted things to be? The progressive notions Jesus introduced rocked that society enough: one was that women were the first witnesses of the resurrection and notified the apostles. If the changes he brought (in reality, corrections to a corrupted order) were enough to get him killed, starting the ordination of women back then would have been small potatoes. But it didn’t happen. The real reason? Either it was what Christ wanted (and therefore His Father), or it was cultural. Currently, the only evidence we have of His intentions is what He did do. Fantasizing about what we don’t know is simply that, fantasizing.

#1: Equating biology with institutional authority. Hmm. Unfortunately, this again ignores the process of revelation. It’s all to easy to say, “they’re just tradition-bound sexists”, and “it’s only an issue of sexism”, but without understanding the process of revelation, this is a treacherous path of logic. If we fail to see just how tuned in the leaders (of both genders) in the church actually are, this appeal to a popular notion seems by its very nature to lack foundation, regardless of the references to the many obscure and less-obsure points from church history.

Loved this comment.

Thank you

What great insight, Observer! Thank you! I completely agree.

I ALSO really appreciate your comments, Observer. It’s frustrating when people use unfortunate examples as the “norm”, or stretch to try to find a correlation to make their point. It’s sad about the girls personal progress attendance. To be fair though, I recently attended an eagle court of honor, where only 3 other people were there (besides the family and scout leader). It most likely has NOTHING to do with the difference in gender. How come the Relief Society generally gets triple or quadruple the budget of the elders quorum and high priests group???? Sounds like there’s gender bias THERE. These arguments presented by the author are flawed in the fallacies it presents, as are several of the points that were supposedly made. You pointed it out nicely. Thank you

Yes. Amen.

It is critical that Church leaders recognize the incredible amount of ecclesiastical abuse that occurs when men are allowed to exercise all power and when women are silenced. During the past fifty years, I have observed an unspeakable amount of abuse of women that has occurred by Church leaders who have little to no oversight in their treatment of women. I have known women who have been raped, emotionally and sexually abused, and driven to the verge of insanity by men who hold positions of power in the Church, including bishops, stake presidents, and area authorities and I have seen General Authorities ignore they cries for help and turn the matter back to the very jurisdiction in which they are being abused.

Any organization in which one class of people have absolute power will abuse absolutely.

These sound like tragic and horrible circumstances. It’s genuinely sad. However, the comment is made as if things like this would NEVER happen “if. . . . “. Guess what? Bad things happen. Good things happen. A group led by men can do amazing things. A group led by women can do amazing things. A group led by men can do horrible things. A group led by women can do horrible things. Let’s not make over-generalizations that negate an actual argument.

By the same token, let’s not abstract away to such a high level that we can miss important points. An organization run only by men can do horrible things to women. It’s easy for you and Observer to brush off bad experiences women have as anomalies so that you can avoid seeing that having the whole power structure of the Church run by men inevitably leads to ecclesiastical abuses. D&C 121 even warns of this. Doesn’t it apply to men too?

Nobody’s arguing that an organization run by solely women would be better, or that an organization run by both women and men would be perfect. We’re just arguing that an organization run by both women and men would be *less likely* to ignore women’s needs, perspectives, interests, and just plain importance as people than the one that we have that’s run by men only.

It’s not run ONLY by men! That’s the part I think you keep missing. Yes, the main leader and charge, and the majority are men. BUT, there is a general relief society presidency. A general young womens presidency. A general primary presidency (all women), There is even a young womens broadcast that is designated specifically for women. There is a relief society broadcast done specifically for women. And the womens leadership goes to the stake and ward level too. In the temples, there’s a temple president AND matron (the matron has several duties that are in HER jurisdiciton). A mission presidents wife also has several things she oversees.

So, once again. It’s not run ONLY by men. Women DO have leadership and opportunities to address needs, give perspectives, address interests, etc. I’m starting to wonder if we go to the same church. ha ha

LKB — great comment

Okay, I run a company and it has a board of directors with 15 people on it. That board has an executive committee with 3 people on it. The Board and it’s subcommittee meet on a weekly basis to set priorities, establish corporate culture, solve big problems and set policy.

We have several corporate officers and vice presidents who have been delegated jobs to do on a temporary basis. Usually their contracts in these positions are 5-7 years, so they get a chance to do some work, but often don’t get the opportunity to follow through on any long term goals. That’s okay, though, because the long-term goals are set by the executive board and assigned to the officers and VPs.

Now, to make sure the officers and VPs are getting the message, they are invited to meet with the board or executive board on a regular basis. Usually every 3-6 months. If they have other ideas or need guidance, we encourage the junior officers to speak with board representatives who are not actually members of the board, but who DO have permanent contractual obligations with the company (basically, they have more opportunity for seeing long-term goals achieved).

So, who makes the decisions in my company? The officers and VPs who are assigned to do tasks during their 5-year contracts? The board liaisons who mentor the officers and VPs and interact with the board of directors more often? The Board of Directors which meets on a weekly basis and has a hands-on approach to guiding the company? The Executive Committee of the Board of Directors which sets the agenda for the Board?

If I look at an org chart for my company, the people with the power are the 15 permanent members of the Board and its Executive Committee. Sure, the VPs and officers and liaisons have responsibilities, but they serve at the pleasure of the board and while they have been delegated power to make decisions and run their day-to-day operations, all major decisions (policy, budgeting, culture) are set by the Board.

Yes. Hahahahahahaha. I’m beginning to wonder the same thing, if you think that female presidencies who *report* to male-only GAs and who don’t serve for life where the male GAs do, and the fact that women “give perspectives” means that they’re running the show in the way the men are. If you’re comparing against the standard of women doing nothing at all in the Church, then sure, women do get to do some stuff. But if you’re talking about actually making decisions at any level that aren’t subject to immediate review and reversal by a group of men presiding over them, then no. Women aren’t doing any of that.

Giving perspectives is not the same as making decisions. Women are locked out of the decision making. Is that really so hard to see?

http://www.lds.org/church/leaders?lang=eng

Ziff – Actually, that is not so hard to see. Once I put on your bitter negative glasses, I absolutely see the misconstrued vision you are describing. I’m sorry you’re looking for things to twist and be angry about. I’m glad I don’t have that kind of personality where I walk in a room, or automatically start counting how much of my “gender” or “race” or “religion” is represented. I know that good people lead this church, and that they were called of God exactly as the Lord intended. Things are done in his time, and not ours. And if you’re really going to be upset about the imbalance of genders, perhaps you should ask him to give a more vital noticeable role to our Heavenly Mother. . . . . . .Obviously, you know more than He does. . . .

Nice, LKB. Anyone who sees the inequality that is actually there is wearing “negative glasses”? I presume that women who wanted the right to vote should have been smacked down with similar comments. “Don’t wear negative glasses, dearie! Think of all the positives! You don’t *need* any rights!”

Really, thanks though for showing where you’re really coming from: prophetic infallibility. You think that if women were supposed to be ordained, they already would have been. Of course, this isn’t a tenable argument unless you believe that Church leaders are infallible transmitters of God’s will. If you do, that’s fine, but you’re effectively turning them into idols to worship. I believe they are merely men, and absolutely clearly capable of making mistakes.

Ziff- The way things are done within a church and the way things are done within a nation are completely different. I just don’t understand those throwing a fit. If I didn’t like the way things were done, and didn’t think they were following God’s counsel, I would leave. No one is forcing them to be a part of a religion that “represses” them. Whereas, when it was a matter of a women’s right to vote, hold a job, gain an education, etc., a woman was very limited in her ability to leave that oppressed state. Women are capable and able to leave their religion at any time, and to go seek out one they feel is obeying God’s command, and giving them the “rights” they want. I am content knowing I am a part of the right one for me. I have never felt that my voice is silenced. (and believe me, I am NOT a quiet person. ha ha) Either you believe the church is run by those who have been called of God, and that they are the mouthpiece of the Lord. . . .or you don’t. There’s no grey area. If you believe, you adhere to their counsel. If you don’t, . . . well, I don’t know why you bother to stick around. So which are you?

Exactly, infallibility. It’s a wild belief, but you’re definitely not alone. You’re wrong, but you’re not alone.

You still didn’t answer my question. Why stick around if you obviously believe everyone that follows the counsel of the prophet of God is wrong?

I didn’t answer your question because it’s not a good question. You want to force me into the infallible belief camp with you or show me the door. That’s just foolish. It’s perfectly reasonable to believe Church leaders can be inspired without being infallible. Here’s my answer: I’m in the sticking around camp, while *at the very same time* believing that Church leaders can, and do, make mistakes. Is your mind blown yet?

So here’s my question for you: Do you realize that treating Church leaders as infallible means you’re effectively making them your idols? God doesn’t like idols.

This a very well thought out and written article and I hope it causes people to stop, pause and consider.

I think they do listen. Instructions from SL are pretty darned clear about how to conduct interviews, etc., and include periodically the stories of incredibly stupid actions on the part of leaders about not listening to issues raised by women. When the prophet or an apostle has to hear of something that’s been ignored at the local level, they can and do get pretty upset, and they make it all-too-painfully clear to priesthood leaders when they instruct them. It’s troubling to hear of such things. Abuse at any level is horrible — the leadership has repeatedly stated that for at least the past 20-odd years that I’ve tracked announcements, perhaps more. For years, the directions have been to avoid certain situations, such as the fairly strict guidelines even as to who rides where and with whom — which have been mocked in some circles. Are they followed universally? I doubt it. Not listening to counsel can and does bring consequences.

If you are a witness to these things — as you state — approach someone who can do something about it. Try church legal (Kirton & McConkie — there are lots of women attorneys there).

On the other hand, in reference to your statement about the “one class of people”: changing the makeup of the class won’t change a thing — abuse can and will still happen. Those in power can grow to love it. The book “Primary Colors” talked about that. To think that section 121 of the Doctrine and Covenants doesn’t apply to woman as well as to men is not supportable. If women think that things will be all rosy if they’re totally in power (to flip the switch completely — I understand that’s not the point here) and nothing bad will happen, well, I’ve witnessed horrible abuse occurring from women to innocents: to children, men, and other women. Neither is that acceptable.

Is the Savior troubled by sin and these things from his own leaders? Of course — that’s very plain from the scriptures.

Benevolent patriarchy is not enough. Male leaders listening is not enough. It just isn’t. That system absolutely requires that every man in authority be not only perfectly benevolent, but perfectly receptive to the concerns of a point of view he can only imagine, in order to avoid abuses and neglects. There is no failsafe, there is no protection. Only the mercy of leaders. Many are good, and do show mercy, and wisdom, and openness to inspiration. But as a system, it still leaves women out, it still leaves them at that mercy. It leaves all women as petitioners, who must plead and beg and cajole and convince, and it leaves them out of decision-making processes that would give them information and insight to see where their problems actually lie and what can be done about them, to be able to effectively convince in the first place.

Does it matter if bad behaviors are doctrinal or not, if that is how the system functions in practice? If there are so very few checks against them, or paths of recourse for women affected?

If every woman is a petitioner, with convincing as her only option for redress, then the burden of proof is always on her. That she exists as a whole human being who should be heard in the first place and be given real time and consideration, that her concerns are valid and there is a real problem, that it stems from things other than her own “unrighteousness,” (often including the need to demonstrate her own worthiness somehow, far too often as “humility,” which is antithetical to the other things she must demonstrate,) and that it’s a big enough problem to warrant actual resources and attention. There is so much cultural resistance affecting every single step of this process. There are women who spend their entire lives cultivating a careful image of performed Mormon womanhood, acquiescing to every cultural more of what a “good woman” is, just to make this process of being heard easier. Because it’s the only way. And those who can’t, or whose lives don’t fit the perfect picture, or who have been affected by other people’s choices, or who have other pressures on their life and can’t dedicate so many resources to looking perfect . . . what do they do?

It is so completely out of balance.

My point was that once women entered that “class of people”, would things get better, worse, or stay the same?

I myself am a victim of abuse, so I know how damaging it is (at least in my own case), and I also have a good guess how the various perpetrators would respond. Some I’d guess would be repentant and apologetic, and some fiercely defensive, but I understand it’s on them, not on me, and my path to healing requires me to forgive. So, once women enter the halls of power, how would things change, if at all? If our local government is any example, it’s not promising.

I am puzzled about your statement about whether or not the bad behaviors are doctrinal? What bad behaviors can be doctrinally supported? That sounds pretty sick.

The Lord is looking for long-term change in all his people. When the Lord asks us to raise up a righteous generation, there are lots of benefits to us as a people and a society, but the benefit to him is a higher caliber of individuals as candidates for leadership. I’m all for that.

The greater question is when will we as a people stop grieving the Lord, and repent and change? There are so many burdens we can’t carry. One of the worst I see are the assumptions about what makes a “good Mormon” or member of the church, which often goes “beyond the mark”.

To think that the prophet is not aware of what’s wrong as well as what’s right in the church would be to be blind, and as he is the individual ultimately responsible to the Lord (who is also painfully aware of what’s going on [see Elder Holland’s talk in the April 2013 General Conference]) for His church on Earth, he also has some insights as to how the Lord feels about these sorts of things.

I’m sorry you’ve been hurt. I hope you eventually got good support and help.

You seem to be arguing that having women represented in decision-making bodies would do no good, so why bother?

It’s true that women would not be any more intrinsically good or less corrupt than men. I reject the idea that we’re naturally so much more spiritual and pure than men are. (Though, if we were, wouldn’t it be a no-brainer to, you know, utilize that?)

But it’s proving in many different spheres that just including women does, in fact, make things better. It shakes things up, it brings a group of people who have different experiences and perspectives into the mix, it brings people who have been socialized differently when it comes to cooperation and group decision-making into the dynamic, and does have a generally ameliorative effect.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/12/04/us-women-leaders-corruption-idUSBRE8B306O20121204

http://hbr.org/2011/06/defend-your-research-what-makes-a-team-smarter-more-women/

Women in visible positions of leadership can also open the way for more practiced respect for women. Countries and cultures where women as leaders and voices equal to those of men tend to have lower rates of sexual assault and abuse.

Women in leadership is just one part of that puzzle, but it’s an important one, and one that I do really believe will have an ameliorative effect. It’s a cultural change that some individuals will be resistant to, and I do believe you that there are some abusive individuals who would not necessarily react well to a woman in authority. But that’s why it must be a broader cultural change. It would be more than just a female leader handling an abuse case. The entire context of how men and women relate to each other in matters of authority must shift.

I’m not saying that bad behaviors -are- doctrinally supported. I don’t claim that they are. That point was in response to another poster above who said that such bad behavior is not a doctrinal issue, because the doctrine is against it. My point is, it doesn’t matter if the doctrine is against it if the practice allows it. If abuse and neglect affect someone, they are still abused and neglected. If women are boxed in by a culture that goes beyond the mark, they are still boxed in.

My main point is, we shouldn’t have to wait for every single person who is guilty of perpetrating these problems to have a change of heart and come around, while people are still being hurt. There is so little safeguard against bad and imperfect actors in leadership positions, and women are specially vulnerable to it, because we are especially subject to male authority. We should be able to address our cultural and structural problems that allow those things to happen, and see if we can’t make God’s church a safer place even when leaders aren’t perfect. Opening up more avenues of power, authority, and visibility to women is one way to correct current imbalances without having to rely on leaders being perfect and prescient at all times.

“You seem to be arguing that having women represented in decision-making bodies would do no good, so why bother?”

What I was saying in that specific particular response, the assumption seemed to be that women in positions of power would solve problems of abuse by those “in power” (in this case, priesthood leaders [males]), and I’m not sure that would happen. You mention that in your next statement, that you thought women were no more better or worse than men, and I’d agree.

Women are absolutely needed in the counsels of the church, and they are. I don’t know if it’s clear or not, but from the handbooks, it should be. It also should have been when at the recent mission president’s broadcast over the summer, almost painfully clear mention was made of it. If people missed it, they missed it, and I think that’s sad.

Brilliantly articulated, Rune.

Observer, where is the revelation? In which verse does God preclude women from holding the priesthood? In which verse does he say that women can perform priesthood ordinances in the temple, but they cannot perform them outside of the temple or that they will never be able to?

I’m not asking you to show me 10,000 ordinations of men to the priesthood, but where does God say that women cannot hold the priesthood now or in the future?

Brent, well done.

Huh? Am I greater than an apostle? I’m not, so I’ll point you to Elder Ballard’s recent talk.

The record of Christ giving his (male) followers authority is in the four Gospels. The pattern in the temple should be instructive: we are only given specific authority to act in certain places and times. There are bounds. At other times in history, few held the priesthood at all. In the Old Testament, under the Mosaic law, only the sons of Aaron and the Levites held the Levitical priesthood (the record of them having to demonstrate lineage is in the Old Testament after the Babylonian captivity). The Melchizedek priesthood was found generally in the prophets.

If your search is for power, I can’t help you at all. Many have gone down that path, but I think it’s the devil’s errand, to distract us from why we’re here.

You haven’t answered my question. I understand that Christ ordained men and they ordained men. I understand that this had been done before, notwithstanding references in the OT to prophetesses and in the NT to female apostles. I understand the emperical evidence of the way it has been done before, but the fact that only proselyting among Jews had been done before was not akin to a proscription of gentiles being taught in the future. The fact that only Levites had been ordained before was not akin to a proscription of people other than Levites being ordained in the future. The fact that most (but by no means all) black men were denied the priesthood prior to 1978 was not akin to a proscription of being ordained in the future. The fact that circumcision had been required for millenia before was not akin to a proscription against doing away with this requirement.

By question for you is:

In which verse of scripture does God preclude women from holding the priesthood? In which verse does he say that women can perform priesthood ordinances in the temple, but they cannot perform them outside of the temple or that they will never be able to?

I’m not asking you to show me 10,000 ordinations of men to the priesthood, but where does God say that women cannot hold the priesthood now or in the future?

Elder Ballard’s talk is instructive and contains the prayerful thoughts of an apostle of the Lord, but it is not scripture. Prayerful thoughts of apostles and prophets have been wrong before. I seek scripture.

Observer, perhaps this thought experiment by Nicholas Taleb might help to illustrate the problem of divining immutable laws off of empirical observations alone:

“Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird’s belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race ‘looking out for its best interests,’ as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, something unexpected will happen to the turkey. It will incur a revision of belief. . . .”

Taleb continues: “What can a turkey learn about what is in store for it tomorrow from the events of yesterday? A lot, perhaps, but certainly a little less than it thinks, and it is just that ‘little less’ that may make all the difference.”

The events of yesterday may or may not write nearly all that there is to know about the future. God’s word, on the other hand, about the future, must be fulfilled. So, what did he say, if anything, in recorded scripture that precludes women from holding the priesthood in the future?

Interesting argument, but I think it’s a false premise in this circumstance. Yes we do expect the sun to come up everyday, and we do expect it to also go down. We also expect lights to turn on when we flip a switch, but we also know that the earth hasn’t shut down if they don’t. We might be turkeys, we might not be. I’d like to think we’re generally not.

As to your query about the “relevant” scripture: we have what we’ve been given. If that’s not enough for you, I don’t know what to tell you.

Which scripture is it that I am not sufficiently crediting? It isn’t enough to say that “we have what we’ve been given. If that’s not enough for you, I don’t know what to tell you.” It isn’t that the scriptures aren’t enough for me (although they aren’t–We believe that God will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God.) But which scripture is it that tells us that Women cannot in the future be ordained to the priesthood?

Loved this. Thank you for putting so beautifully what I am thinking as well.

Beautifully, clearly expressed, Brent. It appears that some readers miss the point that speaking out is ineffective when a segment of the population lacks authority to do so. Like Esther, we wait for the person(s) in power to extend the scepter to us — and risk rejection, ostracism, losing our temple recommends, or, in extreme cases, excommunication — when the “king” decides he’d rather not hear what we have to say.

“I cannot HEAR you,” he says from his throne, surrounded by his wives and their maidservants, who benefit from his reflected power. “The [women in the church] are happy. They sit on boards and governance in the church. I don’t hear any complaints about it.”

This referring to the prophet as a remote, off-in-his-own-world “king” is troubling. While in some ways it may look that way (looked at with partial vision), he certainly understands he’s a placeholder for the Lord. One of my wife’s cousins was in one of the general auxiliary presidencies, and of course we loved to hear about what it was like. She is solid as a rock: a thoughtful, brilliant, spiritual individual, and her husband not one whit behind her. Her take on the prophet was that he did listen.

While it’s easy to project various attributes to the prophet and other leaders, one must also consider whether or not those projections are correct. To see and honor the prophetic mantle is important for any church member. If one wants to see that, it’s possible through personal effort. If change comes to the church, it will come, but it shouldn’t come at the expense of personal testimony, anger, and loss of the Spirit in one’s life. Through difficult courses, I’ve had to learn to choose between the Spirit and anger, and having the Spirit is what a Latter-day Saint needs in his or her life foremost and above all.

Those who wish and agitate for female ordination for the most part have not lost their testimonies, lost the Spirit, or begun living a life governed by anger. That’s a false assumption. The wish for female ordination is for many, including me, inspired by testimony and the Spirit as we strive to become closer to our Heavenly Parents. Desiring to be ordained, as a female, does not preclude having the Spirit in one’s life.

It was not an assumption, but an observation. I was just observing the tenor of the positions expressed here “for” ordination. At the top of the “Feminist Mormon Housewives” site having “Angry activists with (diapers to change, etc.)” next to the banner. Lastly, seeing a degree of compulsion sought in this effort: confrontational activities, etc. There seems to be several groups (on-line) agitating for this, and all are free to present themselves however they wish.

A powerful reflection. As someone who was born into a denomination that began ordaining women before I was born, I can’t imagine what it must be like to hear that your calling is not valid because of your gender. Thanks be to God for voices like yours.

this 70 page paper with thousands of references documents how the revelation came to be.. and what Kimball had to do to get the other to go along with it. https://byustudies.byu.edu/showtitle.aspx?title=7885

Edward L. Kimball discusses the former Mormon policy of restricting Church members of African descent from receiving the priesthood. He examines the traditional and proposed scriptural basis for the policy, its origin and implementation, and the chain of events that led his father, President Spencer W. Kimball, to seek revelation regarding changing the policy. Black Africans’ interest in joining the Church, the Civil Rights movement, Church members’ changing perceptions regarding the priesthood policy, and spiritual manifestations all contributed to President Kimball’s landmark decision. The article describes how President Kimball went about obtaining the revelation allowing all worthy male Church members to receive the priesthood, how the revelation was spiritually confirmed to other leaders, and members’ reactions when the change was announced.

It was a long process with lots of prayer. But the decision came as the obvious choice.. to remain a racist organization or not.. And it was not all that hard to get the brethren to see it.. finally… 15 years after the civil rights act was passed..

Let’s not forget that this priesthood ban on people of African descent began during the time of Brigham Young, and continued for reasons not fully understood. Joseph Smith ordained Elijah Ables to the priesthood, and the Book of Mormon teaches that the Gospel is for “black and white, bond and free.” President Kimball corrected a temporary misdirection that lasted for a little over a century, to put it in line with the universal Gospel that had been in effect for the history of the earth. He restored something that scriptures and history attest had been in effect for a long, long time.

To put a different spin on Haggoth’s question above, I ask: Can anyone show me any instance in which women were ordained to the Priesthood? Any single instance in the history of the earth?

I can show you instances of blacks holding the priesthood before Brigham Young’s ban, but I can’t find a single example of a woman holding the priesthood. Miriam was a prophetess, as was Devorah, and they were spiritual leaders, teachers, examples and warriors. They didn’t hold the priesthood. It appears that priesthood ordination is uniquely masculine in nature.

You can seek to reform or change the church to fit your view of how you wish it were, but please at least be honest about that desire. I have never seen a persuasive argument for female ordination that is based on the doctrines and records of the church. If there is something that I’m not seeing, I’d love to see it.

Romans 16:7 “Greet Andronicus and Junias, my relatives who have been in prison with me. They are prominent among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was.”

Was Junias, a female, ordained to the priesthood? We don’t know. We just know that Paul referred to her as “prominent among the apostles.” I’m not quite sure, by the way, why you relegate Deborah to just a leader, teacher, example and warrior. She prophesied for more than just her family. She is represented as exercising the prophetic mantle.

Women perform priesthood ordinances in the temple, particularly washings and annointings, and at least one other which is performed rarely. You might say that they share in the priesthood of their husbands, but I have known too many single, never been married, sisters who performed these ordinances.

But what you have asked for will only give you so much information. Please see the turkey analogy above. What has happened before tells you only what happened before. It may or may not be indicative of what will happen in the future and it may or may not divulge why something has or has not happened before. I find your observations of what has or hasn’t happened and about what the import of history is, but I don’t find it compelling.

Please re-read my comment about Devorah and see that I called her a Prophetess.

Junias was prominent, but so was Sheri Dew. So were Martha and the Marys. Prominence does not equal Priesthood.

I see what you’re saying with the Turkey analogy (as I did before), but you seem to miss the fact that precedent is of supernal importance to the Gospel. The very fact that it’s never been done before is all that we need to know.

Do we need to improve our discourse and attitudes and treatment towards women? Absolutely! Do we need to change enormous, fundamental cultural biases in the LDS culture to allow women to be their best? Absolutely!

Do we need to change the nature of the eternal Priesthood? That seems unwise.

“precedent is of supernal importance to the Gospel.”

How did precedent control whether to expand the priesthood beyond the Levites? Whether to continue to require, gasp, converts to be circumcised? Whether to keep proselyting efforts just to the Jews to the exclusion of the gentiles? Whether the Sabbath would be held on Saturday? Whether priesthood offices needed to be held by men as opposed to boys? Whether wine must be served as part of the Lord’s supper? Whether men alone can pray in Sacrament meeting? Whether men must be the concluding pray-er in Sacrament meeting? Whether men alone can pray in General Conference? Whether men alone can speak in General Conference? Whether general authorities must be white?

With each of those issues, the precedent continued to be the norm, until it didn’t. Almost always, the change came by revelation. Except for blacks holding the priesthood (where some prophets and apostles said in the name of the Lord that the change would not take place until all the sons and daughters of Adam had their turn), there were history pages full of precedent to justify continuing the way things were, but there were no revelations precluding the change either. I think you have the better part of precedent on your side by a long shot, but I haven’t found any revealed scripture where the Lord says that the priesthood is uniquely male or that it will forever be held or exercised by men alone.

Let me address each example you raised, since they’re all important to consider.

“…priesthood beyond the Levites?”

Levites holding the Priesthood was unique to the Law of Moses, a lesser law that was given for a temporary time. Before Moses, there were no Levites, and the Priesthood was held by many.

“Whether to continue to require, gasp, converts to be circumcised?”

Circumcision was also part of the Law of Moses.

“Whether to keep proselyting efforts just to the Jews to the exclusion of the gentiles?”

Again, only part of the Law of Moses. Abraham preached the Gospel to the Egyptians, who were certainly not Jewish.

“Whether the Sabbath would be held on Saturday?”

I don’t know how that fits in!

“Whether priesthood offices needed to be held by men as opposed to boys?”

I’m not sure what exactly you’re referring to, but the Old Testament/Torah is filled with examples of both men and youth exercising the Priesthood (Samuel, David, etc…)

“Whether wine must be served as part of the Lord’s supper?”

I don’t have a great answer for you on this, other than acknowledging that change happens, but it’s within certain parameters. The color of the liquid we take while making a covenant isn’t quite as weighty as gender matters and the Priesthood, in my understanding. The blood symbolism of red liquid is powerful and important, but it’s a different level of principle at play.

“Whether men alone can pray in Sacrament meeting? Whether men must be the concluding pray-er in Sacrament meeting? Whether men alone can pray in General Conference? Whether men alone can speak in General Conference?”

None of these things are directly related to Priesthood ordination. Some may defend those sexist practices as being related to the Priesthood, but I’d argue that such a defense is misguided. We’re all glad (and a bit horrified that it took so long) that some of these are finally fading away. What does any of this have to do with Priesthood ordination?

“Whether general authorities must be white?”

Define “white.” Our church is obviously run by mortals who are susceptible to mortal biases and mistakes. But what is the eternal principle? That black and white, bond and free are recipients of the Gospel. Most of the prophets of old and our scriptural heroes probably had dark skin. If the euro-centric group of Ephraimite leaders in the 1830s had trouble attracting, training and accepting people from different ethnicities and cultures for a few generations, it was an oversight and not an eternal principle. It was a temporary shift away from a long-standing pattern that’s as old as human history. We’ve had dozens of latino general authorities, we have a member of the First Presidency who speaks English with a strong foreign accent, and I have hope that as the church continues to grow we’ll have a more ethnically and culturally diverse group of general authorities to reflect the people that they lead.

In none of this is there any hint that women have ever held the priesthood in the same sense that men have.

——————

I’m also a bit miffed at the lack of due diligence in support of your argument, here! Nobody is mentioning the fact that Joseph Fielding Smith acknowledged in Gospel Doctrine that women of faith had (in the past) put their hands on the heads of those being blessed, and had for many years stood in the circle during Priesthood blessings (but never acted as voice).

In my mind, that’s a fairly compelling piece of precedent. It doesn’t say that women were ordained to the Priesthood at any point, but it does suggest that women in fact do hold power that might not require ordination before it takes effect.

You may say, “psshhh. That’s healing and miracles. I want to run the church!” Fair enough, but I’ve always been more interested in the miraculous nature of Priesthood blessings than I have been in who exactly is falling asleep up on the pulpit on any given Sunday.

Drome McKauliff addresses the question, “Whether men alone can pray in Sacrament meeting? Whether men must be the concluding pray-er in Sacrament meeting? Whether men alone can pray in General Conference? Whether men alone can speak in General Conference?” by saying:

None of these things are directly related to Priesthood ordination. Some may defend those sexist practices as being related to the Priesthood, but I’d argue that such a defense is misguided. We’re all glad (and a bit horrified that it took so long) that some of these are finally fading away. What does any of this have to do with Priesthood ordination?

According to policy statements in the early 1970s, who could pray/not pray at these meetings had EVERYTHING to do with Priesthood ordination – check your history. The First Presidency said that only priesthood holders could pray at priesthood meetings. They decided that “Sacrament Meeting” was a priesthood meeting – it wouldn’t be taking place except for its central ordinance. Ergo, No Women May Pray there.

Whether it is the examples from the Law of Moses that were the requirement until they weren’t or the Sabbath changing days of the week or the modern early church practice of ordaining only men (not boys) or the sacrament liquid turning from wine to water or the practice of calling only white men to GA positions until (George P Lee maybe??), or gender based decisions about who can speak and pray, precedent did not control the future. Revelation did. The fact that things have always or mostly been a particular way does not consign God to the rut of history.

Perhaps it is the same with male ordination. The practices of the church change, and neither of us are aware of any scripture which would prevent this change.

As for your shock at my lack of depth of knowledge into female healings in the Church, I’m sure you are right. I hope so, because there is so much more that I wish to know. I might have a little more background in the subject than you suppose, however. (I believe, by the way, that you fell into the same trap again. Because I did not share that I know a thing or two about female healing rituals in the Church, you assumed that I did not know about them. Turkey.)

I think you might find the download at http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1064&context=mormonhistory fascinating. It digs fairly deep into our robust history of women healing in the early Church, including citing First Presidency papers giving nuts and bolts advice about how they should lay hands upon other saints in order to heal them. Female healings by the laying on of hands in and outside of the temple was a very common practice in the early church, and really didn’t peter out until the 1940’s. You might also be surprised to learn of Spencer W. Kimball’s biographer’s (his son, Edward Kimball) journal entry cited in the conclusion where it is recorded that Elder Bruce R McConkie in September, 1979 invited Camilla to join in the priesthood circle and lay hands on President Kimball’s head as he gave voice to a priesthood blessing of our prophet.

“Dad had just been given some codeine for headache; he had not said much according to the nurse, but he had asked for a blessing . . . . Pres. Benson was taking a treatment at the Deseret Gym and could not come right away, so the the security man had called Elders McConkie and Hanks; Mother was glad. Elder Hanks anointed Dad and Elder McConkie sealed the anointing as I joined them. At Elder McConkie’s suggestion MOther also placed her hands on Dad’s head. That was unusual; it seemed right to me, but I would not have felt free to suggest it on my own because of an ingrained sense that the ordinance is a priesthood ordinance (though I recalled Joseph Smith’s talking of mothers blessing their children). After the administration Mother wept almost uncontrollably for some minutes, gradually calming down.” Stapley and Wright, Female Ritual Mormon Healings in Mormonism, Journal of Mormon History, vol. 37, p. 85 (Winter 2011).

Heavenly Father’s power is greater than he has shown. Revelation has more in store than we have been able to observe based solely upon history’s wake.

Brent, great article. Well said.

I’m just going to leave this here…it’s titled “9 Wrong Ideas About Women and the Priesthood”

http://thepreppypanda.wordpress.com/2013/04/06/9-wrong-ideas-about-women-and-the-priesthood/

Nice post

I’m just going to leave this here:

” The Church is Structurally Sexist. I can understand this point of view if the church was an organization created by humans, for the purposes of humans, but it is not. It is created by God for his purposes. God loves all people equally and finds no group of souls more valuable than any other group of souls. He is not more eager to bless men than women. I trust that the organization of the priesthood has been designed by God to bless all of his children.”

I find it impossible to take seriously someone who clearly believes that the Church is an infallible conveyer of God’s will.

Ziff, I believe you’re conflating a couple of things about the church.

One is that the church was founded on revelation. The “how-tos” in the D&C lead pretty much to that. However, it is (and was designed to) run by humans. Fallible humans.

This second statement about not believing it is “an infallible conveyer of God’s will”. What in the world does that mean? By “church”, do you mean the Office of the First Presidency, the prophet, the Quorum of the Twelve, the Public Relations arm of the church, the church’s janitorial service, the typos in the lesson manuals, or Aunt Mary’s and Uncle John’s ward in Left Foot, Idaho?

The church (or the Church) can be:

1) the organization (prophets, apostles, etc.) as a lumped whole

2) the members at large

3) only the Office of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve

4) …

Help us out here.

I am that sister who missed out on my daughters baptism because of a locked door (it was actually the woman’s door that was locked). I would have happily baptized my daughter. I would have just as happily given that honor to my son (in fact I was happy he could do that) and then been a witness. I orchestrated everything about the baptism, and I gave a talk which had become a tradition with each of my seven children. But even though I was allowed to do those things, no one cared if I was at the baptism, because I wasn’t needed or important. If I had the priesthood, it wouldn’t have happened. I would have been baptising or witnessing, or even if I was deemed to be unworthy, they would have still made sure the father was right there.

When the bishopric found out that you’d been excluded by the locked door, what happened?

A tragic accident. I have seen so many crowded baptisms, where many family members are indadvertedly pushed out into the hall where they can barely see the ordinance, or can’t see it at all. To have a mother miss her child’s baptism because of such a mixup? A horrible oversight and a tragic thing to have happen.

Does it mean that women need the priesthood? No.

Really great post, Brent. Thank you!

I am a feminist. Women can do anything as well as men(probably better most of the time) and I think all women should be encouraged to “fly”. But, I think it’s important in our quest for flight, that we don’t push men out of the plane to plummet and fall. Men and women are different. Not just based on body parts, but also based on perspective, motivations, and the way they view their place in the world. In Judaism, they believe that women are endowed with a greater degree of “binah” (intuition, understanding, intelligence) than men. And because of this, God gave them the most important task of being a mother and wife. Many argue that you can’t compare motherhood with the priesthood because men are also fathers. Actually, priesthood+fatherhood will never come close to being equal to the spiritual responsibility that is given to a mother. What is more important than fostering love and providing an environment for spiritual/emotional/physical/intellectual growth? You can argue that men have the same responsibility in the home, but I don’t agree. The woman is the captain of the ship. She has the primary responsibility in the home and I think most women prefer it to any calling in the church.