Many of us, whose worldviews have been affected by our changed (or changing) views of Mormonism and its legacy, have come to the realization that without exception, history (and life) is not as simple, neat, and tidy as we had perhaps once thought it to be. During our tenures as elementary and secondary public school students I believe that many of us were led to think of many historical developments in terms of good guys v. bad guys, and that the end result that we read about in the textbook was just inevitable–meant to be from the beginning–and in some cases even the will of God. For example, according to my observations and experience, many Americans conceptualize the African American Civil Rights Movement as being set primarily in the 1950s and 1960s, and that its main actors were participating in a monolithic and unified effort. Any post-secondary study of American history, however, ought to quickly lead a person to the realization that the movement began before the advent of chattel slavery itself and that the individuals participating in it were anything but a monolithic group. They each had in mind different timetables, motivations, rhetoric, methodologies, and even different end-goals for the movement.

Many of us, whose worldviews have been affected by our changed (or changing) views of Mormonism and its legacy, have come to the realization that without exception, history (and life) is not as simple, neat, and tidy as we had perhaps once thought it to be. During our tenures as elementary and secondary public school students I believe that many of us were led to think of many historical developments in terms of good guys v. bad guys, and that the end result that we read about in the textbook was just inevitable–meant to be from the beginning–and in some cases even the will of God. For example, according to my observations and experience, many Americans conceptualize the African American Civil Rights Movement as being set primarily in the 1950s and 1960s, and that its main actors were participating in a monolithic and unified effort. Any post-secondary study of American history, however, ought to quickly lead a person to the realization that the movement began before the advent of chattel slavery itself and that the individuals participating in it were anything but a monolithic group. They each had in mind different timetables, motivations, rhetoric, methodologies, and even different end-goals for the movement.

Though the analogy is not perfect, I see striking parallels between the African American movements for emancipation and civil rights, and the nascent Mormon Reformation (irony intended) currently taking shape.Namely, I see three distinct types of personalities at work within both movements.

First, there are the take-no-excuses, immediatist, even violent, reformers. A few examples:

Nat Turner was a Virginia slave, who in 1831 led a band of fellow slaves in the darkness of a Sunday morning, massacred the people who claimed to be his owners, and then continued the carnage, plantation by plantation, freeing his black brothers and sisters along the way. The emancipation effort continued for two days. When officials caught up to Turner, they convicted him of rebellion and insurrection. They hung him, beheaded and flayed his body, and then quartered the corpse for good measure. Of course Turner’s punishment was surely also meant as an intimidation and deterrent tactic, to keep other slaves in line.

Then there was John Brown, (a white man) who was so passionate about ending slavery, that in 1859 he attempted to take over the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, with the intent to arm the slaves in the area and to then set about freeing all the slaves throughout the entire South, “purg[ing] the land with blood,” as he put it. His plan was by almost all measures an utter failure, and he like Turner was hung for his transgressions. However, his actions awakened slaver, abolitionist, and apathetic citizen alike, causing the country to recognize the urgency of the “slavery question.” After decades of debate, “compromise,” and uncomfortable tension, the Civil War erupted little more than a year after Brown’s death.

Then there was John Brown, (a white man) who was so passionate about ending slavery, that in 1859 he attempted to take over the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, with the intent to arm the slaves in the area and to then set about freeing all the slaves throughout the entire South, “purg[ing] the land with blood,” as he put it. His plan was by almost all measures an utter failure, and he like Turner was hung for his transgressions. However, his actions awakened slaver, abolitionist, and apathetic citizen alike, causing the country to recognize the urgency of the “slavery question.” After decades of debate, “compromise,” and uncomfortable tension, the Civil War erupted little more than a year after Brown’s death.

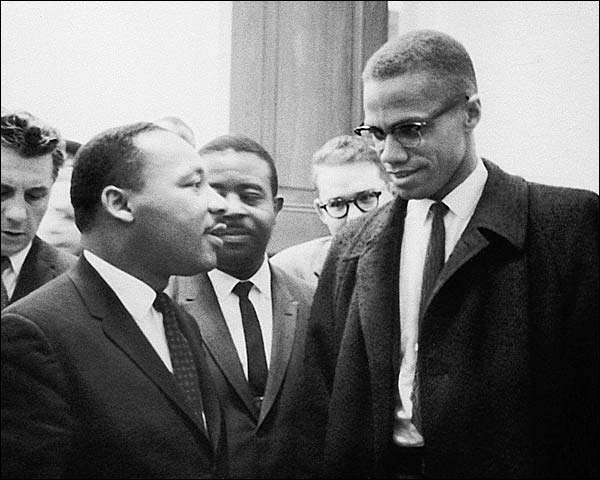

Other immediatists come to mind: Marcus Garvey, who in the early 1900s advocated the development of Liberia, because he was convinced that Africans who had been brought to the New World against their will (and their ancestors) would be better off as far away from their white oppressors as possible. I also think of Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael. They too grew impatient with the timetable and methodology of SNCC and other activist groups more committed to achieving their goals through perseverance and non-violence. They had no interest in desegregation, preferring instead complete separation from the white “devils” that had plagued them for so long.

Second, there is a group who I will call, pragmatists. These were folks, equally passionate about change, who estimated that that change was most likely to occur by utilizing the methods of recourse available to them, rather than resorting to extremism or violence. Though imperfect, these people were resourceful, creative, and inspiring. Think of Harriett Tubman, famed navigator of the Underground Railroad. Dred Scott, who sued his supposed owner for his freedom (and lost). Frederick Douglass. William Lloyd Garrison. Sojourner Truth, an abolitionist AND a feminist! Homer Plessy, who in 1892 refused to conform to the segregation of rail cars in Louisiana, was arrested, and appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court of the United States (and lost).

Writers, like Harriett Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin), also changed the course of history using the strokes of their pens rather than the sword. I am unaware of any defensible source on this, but Lincoln is supposed to have greeted Stowe for the first time saying, “so you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” And of course other rhetoricians were equally effective in advancing their cause–W.E. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, Martin Luther King, Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Rosa Parks, Medgar Evers, and hosts of others.

Writers, like Harriett Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin), also changed the course of history using the strokes of their pens rather than the sword. I am unaware of any defensible source on this, but Lincoln is supposed to have greeted Stowe for the first time saying, “so you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” And of course other rhetoricians were equally effective in advancing their cause–W.E. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, Martin Luther King, Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Rosa Parks, Medgar Evers, and hosts of others.

Finally, there is a group that I will call reticent conservatives. In the quest for emancipation and eventually civil rights, these were the people that desired change, but did not want to be perceived as “uppity” or out of place in expressing that desire. Some reticent conservatives seemed to have internalized their inferiority and felt that they had no right to speak up, perhaps doubting their own consciences. Other reticents did perceive injustice with surety, but worried that speaking or acting out would bring pain or punishment upon them or their families, or even worse that it would perpetuate the stereotype of being unruly, disruptive, and generally uncivilized. In some cases, these people even discouraged overt reform efforts, believing that change would come in its own time and in its own way, according to the will of God Almighty.

***

Each of these groups has a tough lot.

Immediatists feel like settling for anything less than complete and total, immediate change, even abandonment of the system entirely, would be a sacrifice of their own integrity and standards, and would be a concession to the system.

Reticent conservatives are silent cheerleaders-hoping and praying for change, but understandably concerned about what the extrinsic and implicit penalties of advocacy might be.

Pragmatists occupy a particularly troubling space. They are often disliked by radicals and conservatives alike. The immediatists often feel that the pragmatists are far too forgiving of the establishment, and that they have no business trying to make peace with the perceived enemy. Meanwhile, the reticent conservatives are made uneasy by the pragmatists’ “uppity” behavior and the consequences it could potentially have on them, the reticent conservatives. Consequently, without the support of the entire community, the efforts of the pragmatists are complicated. Should they become more assertive in their efforts and join with the immediatists, or be more patient and wait more quietly with the reticent conservatives? Or, should they soldier on, hoping for the support of their brothers and sisters, should positive progress be made?

So how does this tie back to Mormonism?

I think you see where I’m going. If you were to reflect back on these three types of African-American reformers, you would be able to identify a similar group or personality type within or outside of Mormonism. The Mormon Church may not exactly be akin to the American system of chattel slavery or the formal establishment of racism (though there are certainly immediatists that might disagree), but the participants and constituents of the current reform movement within Mormonism bear striking resemblances to the three groups that I outlined above.

I see a group of people who want the church to change immediately, and totally. And even then, if the Church did change they still probably wouldn’t want to have anything to do with it. They want complete separation, and they want that because they feel that is the only ethical option there is. They may be perceived by some as fanatical, angry, or unreasonable, but the volume with which they broadcast their message demands the attention of passersby nonetheless. To that end, they are effective.

I see a group of pragmatists who are passionate about change, but who don’t want their efforts to be undermined by the perception that they are fanatical, angry, or unreasonable. Their efforts are calculated and timely, even if some perceive them as namby-pamby on the one side, or out of line on the other. They are assertive, yet cautious, and probably the group that concerns the Establishment the most.

I also see a group of reticent conservatives–the silent cheerleaders. I don’t know that I gave this group enough credit in my paragraph above. These are important people. Principled people. These are ward-members, brothers and sisters, who may still be unsure of their views, but who would welcome change if and when it came. Though this group may be relatively smaller proportionately within Mormonism than it was within the Emancipation and Civil Rights Movements, my observations tell me that the cohort is growing. These people, though willing to conform to the current model for now, look forward to a more welcoming, egalitarian, less-exacting Mormonism.

So which approach is the best approach? Which group is the most rational, the most ethical, the most reasonable? False premise. None is more important than another. All of these voices are integral and will play an important role in reforming the Church, just as all three groups played an important role in reforming the race dynamics of America.

Certainly there are immediatists, pragmatists, and reticent conservatives who will recoil at the labels I have so willingly placed on them. All three groups would also probably deny that they are actually attempting or hoping to reform the Church. But I see no reason in hiding from this anymore. If we’re not calling for change, what are we doing? Seriously.

Many of us Mormons (former, current, unorthodox, and orthodox alike) want to see a Mormon Reformation, and I think that is something that we need to embrace, rather than shy away from. Surely there will be those that resign from the church, there will be those that face church discipline and are made into examples thereby, and there will be those that remain in good standing throughout all of this, but if there is to be any change made, we must learn from other past activists and advocates and be clear and resolute about what we are trying to do. Just as those that participated in the civil rights movement disagreed about timetables, methodology, philosophy, etc., we too can disagree. But, like it or not, we all seem to agree that change is afoot and that we would like to see it sooner rather than later. Let’s be clear on that point.

***

I discussed these thoughts recently with someone very active in the reform movement. They did not wholly agree with me. They said in effect, “To make an overt call for change and reform would be counterproductive.” They continued to explain that such an affront would likely only cause the church to entrench and dig their heels more deeply into the troublesome doctrines, policies, practices, and teachings that they are currently promoting. I recognize this distinct possibility. In fact, I tend to agree. Calling the church out might be, at least at first, counterproductive.

But I hearken again to the example of reformers who have gone before us. What if they had remained behind the scenes, never making it clear that they were indeed calling for change, sooner rather than later? What if there were sit-ins without Freedom Marches? What if there were arrests for acts of civil disobedience without any attempt to use the media to publicize such injustice? Would change have been unnecessarily delayed? I believe so. Did the actions of abolitionists, defiant slaves, desegregationists, and activists cause the South to entrench and dig their heels in more deeply? Yes, I think so. But with enough publicity and enough support from reticent conservatives and the public writ large, the issues came to a head, and ultimately the establishment had to yield to rationality, justice, and the momentum of history.

At the risk of unintentionally speaking for the entire community of Mormonism here, I would like to suggest a reformed Mormonism that I would feel more comfortable participating in-a Mormonism that is “more welcoming, egalitarian, and less-exacting” than the current iteration. Though I personally do not subscribe to the absolute truth claims of the Church any longer, I do not expect a recantation of everything that makes Mormonism, Mormonism. However, I would appreciate clarity with regard to past changes in church policy and doctrine. “We don’t know why,” is not a sufficient explanation for many of us. I also envision a Church that is transparent, both historically and financially–a church that publicly recognizes its difficult history rather than obfuscating it (no, a few historical-ish Ensign articles and a verbal report in General Conference of the church’s financial solvency does not count as transparent).

I envision a Church that publicly recognizes that, like its own history, healthy gender roles and healthy sexuality are also not as simple as the Church has taught. I long for a Church and its membership that truly embraces the 11th Article of Faith in both word and deed, publicly and privately. Finally, I desperately hope for a Church that welcomes people like me-those who can no longer believe in the absolute truth claims of the church. I need a Church that realizes that the concept of eternal progression transcends the King James Version-inspired concepts of celestial, terrestrial, and telestial, and that attending church can be a way to nurture that progression, no matter a person’s ability to literally believe anything. And thus, I yearn for a Church that values and emphasizes the unity of earthly families as much as it does the unity of eternal families. I want a Mormonism that realizes that mental health is a prerequisite to spiritual health-not the other way around. And today, for personal reasons, I look forward to a Mormon leadership (from GA to Relief Society President) that actively seeks to eradicate unhealthy folk doctrine, hurtful cultural practices, and harmful trends within the church.

Some say that such a Mormonism is impossible. Others say that such a Mormonism is inevitable (in time). I posit, however, that such a church is neither impossible nor inevitable, just as the deconstruction and eradication of racism is neither impossible nor inevitable. The realization of such a version of Mormonism is only possible to the extent that we, who have been so deeply shaped and affected by the Church, continue to care enough to be vocal and open about our desire to see Mormonism change–for the better. I, too, have a dream.

-Submitted by Matt Lorenzen

well done–

There is always a problem of the conflicts within any troubled group–

It is easily seen today; there are African Americans who have done well and been successful, at least financially and socially, since the civil rights movement, and there are those who have not. Civil rights means very little to the young man who is trying to get ‘ahead’ by selling street drugs and loses his life or is imprisoned trying to do so–

To the truly ‘poor’ Mormon much of the struggle those who are wealthy enough to know about the inequities are having seems irrelevant.

What many of us long to see in the Church is honesty, a question that must be answered affirmatively to receive a temple recommend. We want honesty concerning Church history, changes in the temple ceremony, the similarities between Mormonism and Masonry, the reason blacks and women have been marginalized in the Church, the Church’s history of polyandry, and the statements of the prophets that are so far-fetched, ie. the Adam/God teachings of Brigham Young. We want the Church admit that prophets of today are flawed and imperfect just as biblical prophets were. We want people like Lavina Fielding Anderson to be allowed to document eccelesiastical abuse in the Church without being excommunicated.

What a great article! I’d easily put myself in the’ pragmatist’ camp and sometimes it’s a frustrating place to be. Just yesterday I listened to the recent excerpt from the General YW pres., Sister Dalton, that once again told women that if they truly understood motherhood they “wouldn’t lobby for rights.” This thinking has got to go. People can’t be made to feel that any urging for change is a result of personal flaws or misunderstandings. I’d like to see a time when we can openly put uncomfortable questions on the table and where belief, in its various forms, is allowed to look differently for different people. We need to get to a place where “We don’t know why” is sometimes replaced with a resolute “We were wrong, I’m sorry” or at least a “You’re right, we should look into that.’

I think there are many that share in your dream. Thanks for the thoughts.

Yes to everything you said, Danielle. Just “yes.” ;)