This is a guest post I wrote nearly a year ago on my wife’s column (Knit Together). It’s as relevant as ever (e.g. DHO is still running around arguing that the proper practice of our religion requires us to work to prevent marginalized groups from exercising their basic civil rights–which is interesting, because I quote some of his other writings below to refute this argument).

My name is Brent Beal. I’ve been married for eighteen years. My wife and I have three beautiful kids. We are both university professors, we’re Mormon, and we support gay marriage.

I support gay marriage for two reasons.

Heroic Aspirations

People are people. On our bad days, we’re capable of unforgivable indifference and unimaginable cruelty. On most days we muddle through-we help each other out, we keep each other company. On good days, we do things that make the world a better place.

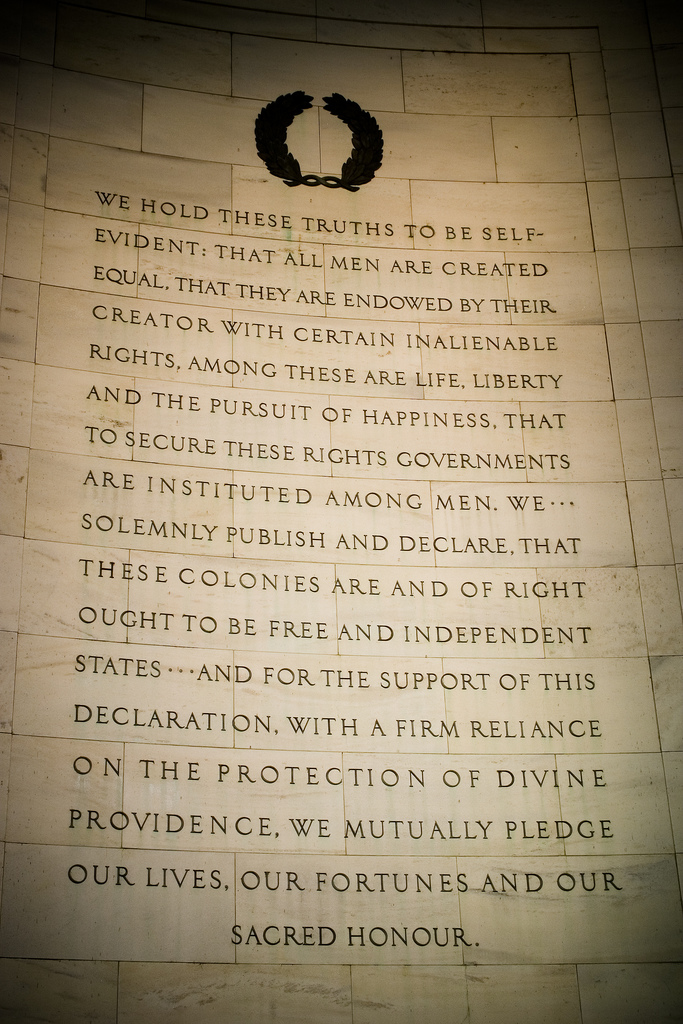

There are quite a few good days in our history. For me, when it comes to the issue of gay marriage, one day, in particular, sticks out: July 4, 1776. This is the day, of course, that the committee of the whole of the Continental Congress adopted the final draft of Declaration of Independence. Here’s the second sentence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

When I was younger, I found the reference to God comforting. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to a deeper understanding of the wisdom of referencing God as the ultimate source individual rights, but I also see now that that’s not the source of this passage’s power. What this passage does, in a heroically aspirational way, is elevate basic rights-the right to Life, Liberty, and pursuit of Happiness-above all else. The existence of these rights is not open for debate. They cannot be put up for vote. The majority, even in a democracy, cannot take them away from the minority. All men are created equal, and they have certain rights, full stop. Notice that not only are these rights set safely beyond the reach of government-they are put beyond the reach of everyone, and that includes those who think God has informed them otherwise.

This is an incredibly important concept. We are not so much a “Christian” nation as we are a nation where certain unalienable rights have been put out of the reach of religion, Christianity included. We are not a great nation because we believe in the right God, we are a great nation because everyone is free to believe in whatever God they choose, as long as-and this is critical-as long as everyone understands that their right to impose their understanding of God ends where others’ rights begin.

This ideal is aspirational. It requires effort. Equity, fairness, a belief in the worth and dignity of the individual, a commitment to the rule of law, and a willingness to respect the rights of others even when it’s not convenient-these are not easy things. We’ve been trying to live up to these ideals for more nearly 250 years. Sometimes we have fallen shamefully short. We have had to go back again and again, hold those ideals up to the light, and see our own deficiencies reflected back at us. Trying to live up to those ideals, I believe, has made us a better people.

Public policy is serious business. We should deliberate carefully before making changes to foundational institutions. Bringing religion into these deliberations, however, makes no sense if you believe in what Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence. This debate is about whether or not a significant segment of our population is going to have equal access to what all parties acknowledge is an important social institution. We are debating whether or not fellow Americans will be allowed to fully engage in the unalienable rights of Life, Liberty and Pursuit of Happiness. Because this debate is about individual rights, it is above the pay grade of religion. I may hold certain religious views on the matter. You may hold different religious views. Both our religious views are irrelevant. The only question is whether or not granting these rights gets us closer to the ideal of treating all men equally and making sure everyone has equal access to Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

The first reason I support gay marriage, therefore, is because I believe in the values and ideals that our country was founded on.

Religious Freedom

The second reason I support gay marriage is because I believe in religious freedom.

For those of you that are familiar with Mormon history, you know that the Mormon church has been on the receiving end of religious intolerance. Those experiences have, I believe, made us more tolerant-at least for most of our history.

One of our Articles of Faith-an official summary of our principal beliefs-states that “We claim the privilege of worshiping Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience, and allow all men the same privilege, let them worship how, where, or what they may.”

Heber J. Grant, an early president of the church, stated in a church-wide conference, in April 1921, that “We claim no right, no prerogative whatever, to interfere with any other people.”

A few years prior to that statement, in 1907, the First Presidency of the church, stated categorically that “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints holds to the doctrine of the separation of church and state. . . . We declare that from principle and policy, we favor the absolute separation of church and state. . . .”

In 2006, this same sentiment was repeated in another official church statement: “Elected officials who are Latter-day Saints make their own decisions and may not necessarily be in agreement with one another or even with publicly stated Church positions. . . officials must make their own choices based on their best judgment and with consideration of the constituencies whom they were elected to represent.”

In 2009, Dallin H. Oaks, a church leader, warned church members in a speech given at BYU-Idaho that “fragile freedoms are best preserved when not employed beyond their intended purpose” and that members should be careful “never to support or act upon the idea that a person must subscribe to some particular set of religious beliefs in order to qualify for public office.” The danger, Oaks warned, is that if such a standard were to be employed, then those elected under such conditions might attempt to use government power to support their religious beliefs and practices, and the “free exercise of religion [would be] weakened at its foundation.”

We have a long history of behaving ourselves in the public square. We recognize, as do other thoughtful people of faith, the blind alley of religious argument in the context of political discourse. If I bring my religious beliefs into the public square and assert that my understanding of God should be enshrined in public policy, what is to prevent people of other faiths from doing the same? When our respective views of God conflict, then whose interpretation should be given precedence? We could each cite as evidence our respective spiritual impressions and experiences, but in the end, we would find ourselves with no effective way to referee the impasse. If you claim that your experiences are superior to mine and that your religious views should therefore be given precedence, then what is to prevent me from making the same claim? It is a blind alley-and the only safe exit is a mutual agreement to use the general welfare as an arbiter. In other words, when we leave our private lives and enter the public square, we leave our respective religious views at the curb. We talk about what is in the best for everyone. We debate, we compromise, and we figure out how to live together. And we leave God out of it (at least until he gets his story straight and starts telling everyone the same thing).

When I approach the issue of gay marriage from this perspective, the right choice seems clear.

The Decline of Religion in Public Esteem

When we use religion as a basis for public policy, we bring it into a contested domain. When we allow religious beliefs to be enshrined in law, we privilege certain religious views over others, and that puts the delicate balance that supports religious freedom at risk. If I can impose my religious views on others today, then what prevents them from doing the same to me tomorrow? If I can keep someone from marrying today because that is what I believe God wants, then what happens when they invalidate my marriage tomorrow because that is what they believe God wants?

We protect and preserve our religious freedom by keeping religious views out of the public square.

So why did the Mormon church get involved in Prop 8? I don’t have an answer.

Dallin H. Oaks recently gave a speech at Chapman University School of Law in which he bemoaned the ascendancy of moral relativism and the decline of religion in public esteem. He and other church officials have, on numerous occasions, defended the church’s opposition to gay marriage.

When I read the speech, I couldn’t help but assume that he was throwing me in with the moral relativists. I couldn’t disagree more. I support gay marriage because I believe in values and ideals that haven’t changed. What’s changed, I hope, is our capacity to live up to those ideals. In my opinion, the decline of religion in public esteem should be attributed to religion’s failure to live up to these ideals rather than to any imaginary wounds inflicted by moral relativism.

A Truly Religious Experience

For me, it was truly a religious experience to listen to President Obama’s remarks at the signing of the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act of 2010:

For we are not a nation that says, “don’t ask, don’t tell.” We are a nation that says, “Out of many, we are one.”

We are a nation that welcomes the service of every patriot. We are a nation that believes that all men and women are created equal.

Those are the ideals that generations have fought for. Those are the ideals that we uphold today. And now, it is my honor to sign this bill into law.

Is it too much to ask that the message we get in the pews on Sunday be as inspiring?

Brent,

That’s the clearest explanation for supporting gay marriage I’ve heard. Thank you for posting!

Thanks for the encouragement.

This so clearly articulates my own thoughts and feelings, Brent. Thank you.

Our Church has expected others to accept our practices, which is the early days of the Church included polyandry and polygamy. It seems hypocritical that we not respect and honor our gay brothers and sisters if they desire to marry.

I loved this the first time around. Thanks for reprising it.