‘Zion’ has become a dirty word in our world: now it is shorthand for the displacement of native peoples from their homelands, and a justification for the flexing of military power for scriptural causes. I’m not sure that when my people sing songs about ‘Zion’ that they’re thinking of these overtones: and when I talk about the concept, I certainly don’t mean these things.

At the other end of the spectrum, there’s a parallel tradition of ‘Zion’ which constructs the concept in the mind and the heart, as a ‘Utopia’ (or no-place). LDS scripture suggests this in some places: “for this is Zion – THE PURE IN HEART” (D&C 97:21). This conception is given by diaspora Jewish people, and perhaps fits with the LDS idea of ‘the stakes of Zion’: the interpretation after the mid-20th century that resulted in the instruction to converts to no longer emigrate to Utah on conversion. The LDS Church has consequently begun to remake itself as a player in a pluralist society, as one influence amongst a competing influx of influences. Yet, this may seem to cut against the very core of what Zion is, in both senses. How can an adult in our media-saturated world remain ‘pure in heart’, without becoming blinkered?

I still believe this is a question worthy of careful consideration. This is because I still believe in Zion, in the sense that I always believed in it: as a community of like-minded friends. Zion, to me, is feeling at home, not just in our home, but in a ‘zone’ one step wider: in the streets and market-squares. It is feeling in harmony with the world: that we’re working together for a common goal.

Of course, I need to be clear that I’m not talking about any kind of Communist/Socialist project. I’m aware that capitalism offers the confluence of ideas, people and competition that helps to avoid stagnation. I’m not suggesting a model: but I am expressing a desire. A yearning: and not just for a state of mind, but for a place.

Places do matter. When I step out of my front door, my mind necessarily interprets and responds to my environment. I live in a pluralist society, so the competing streams of media messages cut against the feeling of ‘home’. They tell me I need more, and different: that my family is incomplete without, for example, the new high-tech toothpaste. The countryside is more responsive to my desire for ‘home’. The villages, even more. Yet even the villages near where I live seem to have less of a sense of community than anywhere else, with their security systems and guard dogs.

As an odd and idiosyncratic model of the psychologies of ‘Zion’, allow me to briefly dwell upon a small tribe of Gauls, who, I read, inhabited the last remaining outpost against Roman rule in BC 50.

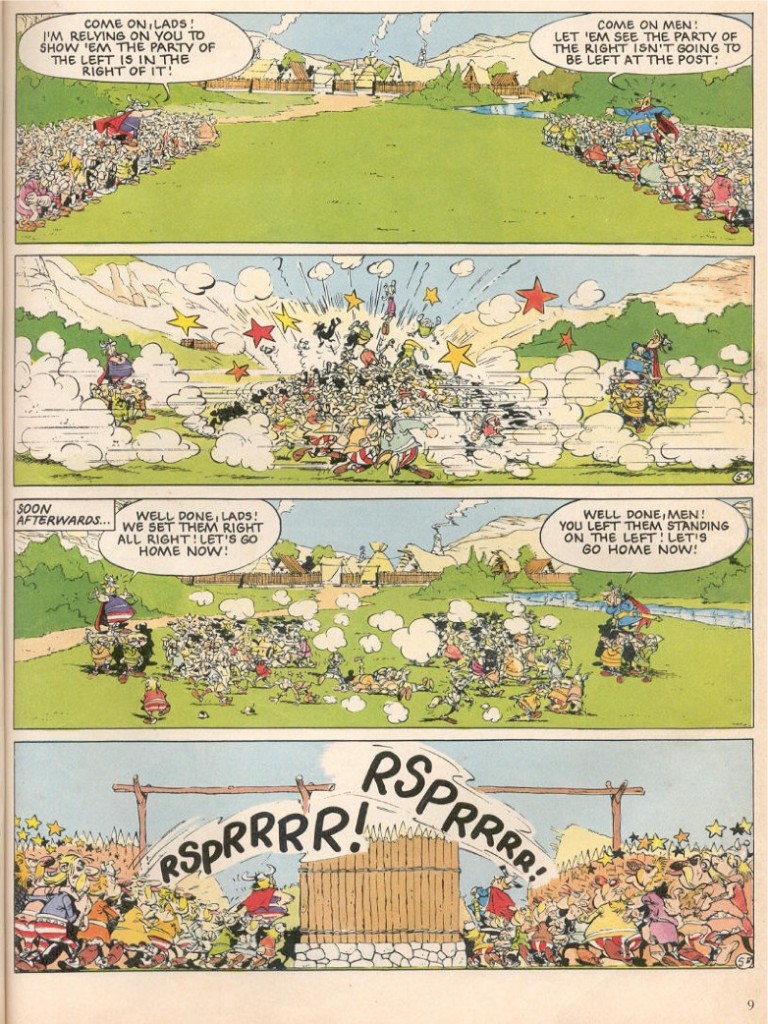

I loved the Asterix books when I was growing up. You probably know the backstory. If not, I refer you here. The community that the village enjoys is created by their opposition to endless legions of Roman soldiers, who they regularly sally forth to beat up, thanks to the magic potion that they possess. Sound familiar? The psychology expressed in Asterix is, in some ways, functionally similar to the LDS/Christian/Jewish conception of ‘Zion’. It is defined in opposition to ‘The World’/Heathen nations/Babylon, and is empowered by this energising tension. A wall is constructed around the village, and those inside are friends: those outside can’t be trusted.

The result of this containment, of course, is community. The village has a bard, a strongman, a chief, and a hero, and a practitioner of each essential trade. The village is self-sufficient, and works and celebrates together. Everyone knows everyone else, solves problems together, and would risk its neck to save one of its own. It’s a wonderful picture: one that inspires the most idealistic, and strengthens the weakest.

But could it be possible to have ‘Zion’ without ‘Babylon’? The psychology of ingroups and outgroups is deep-rooted. I want to find a better model, though, because the aggressive tension of the model I’ve described can, in my opinion, have a dark side, which places it in opposition to the higher ideal of a wider friendship and community. I don’t want to have to beat up any Romans, or demonise anyone in order to have this community.

When my family was about to emigrate to Australia (I was seven years old), my school class gave me a book: a gift with a beautiful metaphorical significance. The Asterix story ‘The Great Divide’ tells the story of a single village, elsewhere in Gaul, that has been divided by disagreement between two rival chiefs and their followers. A schism years earlier has caused the inhabitants of the village to cut a huge trench through the ground, and even the houses and buildings, to materialise their opposition. The story invokes the age-old romantic tale by introducing a boy and girl, who, from either side of the Divide, fall in love, and necessitate a change in the attitudes of their communities. Perhaps it’s idealistic of me, but I can’t help but hope that this other drive – for love – could unite us with those we have been estranged from, across the self-imposed Divide.

How wide is your circle of in-group, versus your outer sphere of those you consider ‘Other’? We all, biologically, come programmed with this psychology. But I’m interested in hearing about what experience you have had with lowering the ‘wall’, removing the battlements, and perhaps – finding that those outside aren’t ‘baddies’ after all.

Where we have felt distance and difference, perhaps our generation will rise to see harmony and love.

Oh, I loooooove this! Fantastic food for thought. Thank you for the examination of Zion in these varied contexts.

I think the thing life keeps teaching me over and over is that there are no ‘others.’ No one is separate from me and the walls I create are more about me — my fears, my aversions, the things that I don’t like or understand about myself — than they ever are about another person. Ironically, I have learned a lot about this living in an insular community like Mormon communities typically are. I have had the opportunity to love and extend myself to people that I probably would not choose as friends and I am profoundly grateful for those opportunities.

It’s true: the paradox is that in ‘the village’ we have opportunities to erase ‘other-ness’ within that limited container. So you could read it as a way of just ‘starting small’ with love and community.

I totally agree though – there are no ‘Others’ outside of our own mind. The walls are in the mind, first… then we construct them in the real world, sadly.

I think viewing oneself as being involved in an epic struggle between good and evil is very seductive. I am a little ambivalent about an “opposition in all things” mindset because it makes it so easy to ignore our doubts, especially about things from outside our cultural comfort zone. Cruelty becomes much easier to justify when dealing with your “opposite”.

Wow, interesting connection with that scripture, Colin. I’d not thought about the ‘opposition in all things’ making us polarise our worldview… but surely that must have an impact. It’s a core scripture in LDS teachings.

I’m reading A.C. Grayling’s ‘The Good Book’ at the moment, and it’s making me think about the possibilities for rewriting LDS scripture in a less objectionable way… How might you recast that scripture that you mention? Perhaps:

‘For in some places, there will be opposition, and in some places, harmony. This must be so, my first-born in the wilderness, for the world is full with both conflict and flow. Therefore, amongst this confluence, seek righteousness: to bring it to pass from the midst of what first appears as holiness or misery, from the shadow-play of good and bad.’

I like that a lot.

“For behold, sometimes things are weird, and sometimes people are different. Yea, gird up your loins, for the best food comes from other ethnicities.”

Lol! Love it.

In fact, the words that were revealed through you are inspiring me right now to go and get something to eat from downstairs.

Amen and Amen.

I’m going to have some magic potion, la la la.

I think that’s prohibited by the Lord’s Law of Health (TM), m2theh!