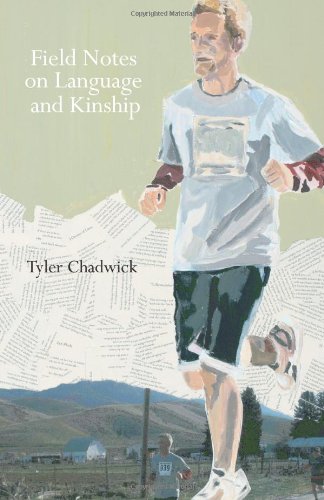

If you enjoyed reading Fire in the Pasture (Peculiar Pages, 2011), then you will want to get your hands on Tyler Chadwick’s latest publication, Field Notes on Language and Kinship (Mormon Artists Group, 2013). Fire in the Pasture is an extraordinary compilation of contemporary Mormon poetry, gathering in poems from a wide range of Mormon artists. It is an edition remarkable for its inclusivity; it seems Chadwick used the loosest possible definition of “Mormon” when he selected pieces for publication, and so the anthology he produced is one of stunning variety. This book was long overdue; the last compilation of Mormon poetry, Harvest, was published in 1980. With Fire in the Pasture, Chadwick has given the entire Mormon community a rich gift.

If you enjoyed reading Fire in the Pasture (Peculiar Pages, 2011), then you will want to get your hands on Tyler Chadwick’s latest publication, Field Notes on Language and Kinship (Mormon Artists Group, 2013). Fire in the Pasture is an extraordinary compilation of contemporary Mormon poetry, gathering in poems from a wide range of Mormon artists. It is an edition remarkable for its inclusivity; it seems Chadwick used the loosest possible definition of “Mormon” when he selected pieces for publication, and so the anthology he produced is one of stunning variety. This book was long overdue; the last compilation of Mormon poetry, Harvest, was published in 1980. With Fire in the Pasture, Chadwick has given the entire Mormon community a rich gift.

In Field Notes on Language and Kinship (Field), Chadwick gives us yet another gift: a companion book of notes to Fire in the Pasture (Fire). These notes vary in length and genre. Sometimes the notes are original poems Chadwick composed while editing Fire. Before each of these poem-notes, Chadwick includes an introductory paragraph or so explaining the relationships between his poems and the poems in Fire. Chadwick is an excellent poet, and so these entries, for me, are particularly delightful to read. One example, one of my favorites, is a prose poem called “Siren”:

“I only saw her once. While I was pacing the halls of an old folks’ home, she spoke from the crosshall-where other patients slept or stared, heads cocked against wheelchair frames, saliva fanned across sweaters and soiled linens-her hands raised, fingers curled upon themselves, tempting those who could bear her straying eye and rotten smile to share forgotten bread.” (Field 89)

Do you hear the sibilance of that second sentence, “she spoke from the crosshall-where other patients slept or stared”? All those esses accumulate to make this old woman/siren snake-like, soothing and menacing at the same time. I found this poem haunting in its familiarity, the old woman’s repeated question, “Have you ever had a Greek pastry?” following me into my sleep.

Field also has notes that range from essays to short-and-sweet analyses of different poems in Fire. Some of these notes were difficult to understand without going back to Fire, rereading and ingesting the poem anew, and then returning to the analysis. In this way, Field really is a companion book to Fire, the one completing and commenting on the other.

The multigenre format of Field opens the text to multiple ways of approaching it as a reader. You don’t have to restrict yourself to reading it from cover to cover. The format invites you to skim over sections, or just focus on the poetry if you want to. The book begs to be read differently, in pieces, not necessarily in order. However you choose to approach the text, I guarantee it will be a leavening experience.