Today on ‘The Sanctuary’ we’re very pleased to have a guest post from Krisanne, who writes at the Mormon Women Project, as well as A Paper Moth and Bottari.

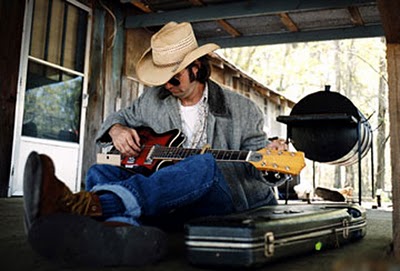

A couple of days ago I watched Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus, a documentary about an alt-country musician’s travels through the deep south–the jukebox bars and two stop light towns south; the eggs over easy cafes and tattered confederate flags south; the come to Jesus or forever hold your peace in Hell south. What struck me the most was the vivid and unapologetic definition of morality within these Pentecostal communities; there seemed to be an almost mythical distinction between black and white, good and evil, and heaven and hell. A good portion of the film followed around those who didn’t subscribe to their community’s Christian ideal: the barflies, the inmates, the sexy honky tonk bar dancers. The narrator said of those on the margins: “They bury their powerlessness in the rituals of sin.”

I wonder about this idea of sin as it plays out on the personal stage. I’m not a big fan of the word ‘sin’ particularly because of the way in which it’s often used. I think for many Christians, there is an albatross of guilt and shame that hangs heavy from that word so as to invite self-flagellation more often than divine restoration. The word ‘sin’ literally means “to miss the mark.” For me, to sin is to mis-remember who I am; it is to aim my energy towards some thing that is inherently not divine, not godly, and thus not me. What is required to realign this misalignment? It is to re-member who I am; it is to re-invision myself as a member of all things holy; it is to re-orient myself with God through prayer, meditation, fasting, and studying sacred texts.

I also wonder about this idea of sin as it plays out on the collective stage. In qualifying someone else as a sinner, do we collapse the space and compassion necessary to help them re-invision themselves as a member of all things holy? By way of example, the phrase, “Hate the sin but love the sinner” is deeply problematic in part because it creates a false distinction between those who sin (them) and those who do not sin (us). The reality is that no such distinction exists. We all miss the mark on a consistent and frequent basis; we are all the same in this regard. In thinking about appropriations of the words ‘sin’ and ‘sinner’, I have to get painfully honest with myself. In my fear of being cast as a sinner, do I ever bury my authentic voice under saccharine notes of all-is-well-in-Zion? Do I ever push those members of my congregation I deem as “sinners” so far to the margins that they are forced to seek communion elsewhere? Do I ever exclude some members of my spiritual community from the rituals of godliness and then shame them for finding comfort in the rituals of sin? These are hard questions. I have to check myself. Constantly I have to check myself. What do you think?

;

;

I like your definition of sin. The more I question, “what is sin?”, the more my fear of it dissipates and I realize that there are many things that are divine that I never saw before.

I love this post: thanks so much for this, Krisanne.

I LOVE Tom Waits, another (could you call him alt-something?) musician. He plays on these questions of sin, the mythic black-and-white, to brilliant effect: casting himself as the sinner (all barflies do this too, don’t they?). In doing this, and identifying his character on stage and in his music as ‘hitting’ the other mark, he can bring all the powerful mythology into action to muse on mortality, guilt, and the human condition.

I think the appeal of this kind of narrative for me has been proportional to the fading power of the ‘all is well in Zion’ narrative, as you say. The saccharine is so deadening after a while, isn’t it? Too many sweeties, and nothing tastes worse than sugar. Funny: this metaphor has found a literal effect for me, too. I can’t eat too many sweet things nowadays! Coincidence?: who knows.

I really think that range of feeling and experience is essential, though. Surely we all need times to reflect on our sinfulness and processes of decay, and equally: our goodness and constructive desires. Both are fundamentally human.

Laurie–I love how you link exploration and questioning with the dissolution of fear. I believe that seeking and exploring are vital if we’re ever to progress from a fear-based paradigm to a love-based paradigm.

Andy–Thank you for making that point that we need to reflect on our goodness as well. To be fully authentic requires honesty about all of our corners, sharp and smooth. I’ve been thinking that maybe authenticity is the epitome of Christianity. Jesus Christ was deeply connected to humanity because of His authenticity. It’s a good lesson for me to remember as I move through my days: to be authentic is to be charitable and connected.

Thanks Krisanne. I keep trying to get someone to shoot me down on my morally relativist position, though: I just don’t buy that there’s a ‘mark’ that’s anything but socially constructed, and therefore, able to be rewritten (although, perhaps not in one lifetime).

It’s really interesting to think about the relationship between authenticity and Christianity, and specifically, the teachings of Christ. I think I tend to feel that the individual (at least, potentially) has the best chance of access to the ‘real’ self, so the whole idea of any kind of rabbi coming along and giving a moral code from an external vantage is problematic for that. However, I think you could argue that the teachings of Christ were not external-type laws (eg. as he cast the Pharisees), but appealed to internal analyses and conscience. In that case, I think you’re right: and Christianity is true to its origin when it follows in this mode.

Andy, what do you think about very basic ‘marks’ — kindness, compassion, mindfulness? I would agree that the forms those things take are fluid and ever-changing, according to the people and situations involved, but the marks are still there.

I like the idea of finding rabbis to teach me, but I think that must be held in balance with the internal barometer — being a lamp unto yourself, as Buddha taught.

Heidi, I think that even those marks are socially constructed… but I do believe that behind those marks are some biological realities: that our DNA, through the countless generations, are coded to make our minds work in certain ways. These are hard-wired: and I don’t think they are able to be rewritten, at least, not for our generation. However: I think there’s more latitude for how we interpret these realities than we realise. Of course, ‘kindness’ works, insofar as it accords with an evolutionary need for social cooperation. But equally, another conception of this same evolutionary need might look quite different, and still work just as well – or better.

To bring this round to the subject of the OP, I feel that ‘sin’ is not the most useful paradigm, as it seems to suggest a pre-application of natural consequence with a law as it is understood by our minds. I’d sooner take the man-made ‘hedge’ away, and allow people to experience – as far as reasonably possible – their own realities.

There are big problems with this, though: to take a shot at my own morally relativist position, I accept that the barfly, in his(/her) self-medication, often hurts the people who love him. A socially-accepted morality means that we hurt each other less… but there are costs attached: which I reflect upon a lot.

Beautiful post. I was also struck by the way you describe sin. I think too often we misunderstand the nature of sin and get bogged down in the shame and aversion of “I did something bad.” Missing the mark contains the suggestion of trying again, the space to remember who you are and find a better way.

Thank you, Heidi! I completely agree. I believe that generally we do the best we can with what we have at any given time–if we could have done something differently we would have. Because we’re imperfect in our understanding and perspective, we will consistently miss the mark. With that said, I think we get a little closer to the mark each time we try again.