Nobody would want to be called a ‘Fascist’. Unless, of course, you’re living in 1930’s Italy: the world of Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970). The film follows a man: an aspiring Fascist operative, Marcello, on his way to assassinate his former professor, a political exile in Paris. On the way, through a series of complex interweaving flashbacks, we see a number of Marcello’s close relationships in development: most prominently, his marriage to Giulia that provides (in a honeymoon) a coverup for his trip to Paris, and the promise of ‘normality’. Yet The Conformist presents normality as alienation as it follows this strange and driven protagonist. We twice see Marcello against a crowd, dancing or marching — and both times he is exposed by the tide of the people. Confused and alone, he is shown up for his individual obscurity in the tangible mass of men, women and children that make up a society.

Fascism preached that the individual gains his or her sense of identity through state-sanctioned culture: a common, and not a unique or pluralistic self. In his journey, Marcello comes in contact with a range of ‘Ideological State Apparatuses’ (as Althusser termed them), and in each case finds himself at odds with them. His family is dysfunctional: his mother addicted to morphine and his father in an asylum. His visit to the Priest results in a disillusioned short-circuiting of the reasons and morality of the hollow absolution given there. As he speaks to his former professor for the first time, we learn of Marcello’s promising progress as a student, and his failure to follow his thesis after his professor left the college. Breaking through the veneer of each of these institutions is a powerful combination of sex and death, which for Marcello are linked by a vividly remembered childhood experience. As a boy, he was rescued from molestation at the hands of his peers by a chauffeur, with whom he began to have a sexual encounter — cut short by Marcello flying into a rage, shooting bullets into the walls and the chauffeur.

The Conformist is visually, a landmark. Filmed with the assistance of the brilliant cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (Last Tango in Paris, Apocalypse Now), it contains some of the most beautifully composed scenes I can remember, from any film. Light crosses the glorious, spare halls of the Fascist bureaucracy, the fashionably furnished homes of the elite and the dreamlike woodland roads. So often, light travels in diagonal lines: through shutters, or breaking through treetops. Angled like a scalpel, it moves and crosses the beautiful, bust-like faces of the characters, challenging their hopes for order or fixity. Yellow lines illuminate particles of dust in their brief suspension in the air: the transience of the world which Marcello seeks to build and live within.

The film closes after the fall of Mussolini, as Marcello travels into the city, ‘to see how a dictatorship falls’, as he says. With his blind friend Italo, he walks among beggars: one of which he recognises as the chauffeur who he thought he had killed as a boy. In a panic, he shouts out, accusing the chauffeur of homosexuality and the murder of the professor, and his friend Italo of being a Fascist. The paradox of Fascist dictatorship is echoed in Marcello’s deflection of blame: a state that sanctioned the bounds of identity attempts — with futility — to relieve the self of the burden of the responsibility for personal choice. The film’s final scene carries echoes of St Peter’s moment of accountability during the trial of Christ. At the dawn of the new era of an anti-establishment gospel, Peter committed the sin of trying to pass on his personal responsibility and his dangerous identity. The Conformist leaves us with Marcello considering the gravity of his betrayal: alone in a new world.

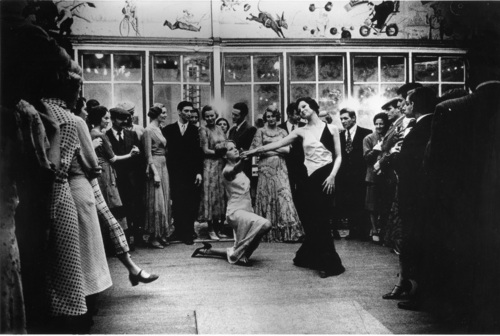

Against Marcello’s individualism, the beautiful enacting of the dance is the hope of the film. Giulia and the professor’s wife, Anna, dance together, with the crowd around them, in a wonderfully free and socially redemptive scene. Joining hands, the crowd move around the square room, a joy that can last, at least, for the night.

NEXT WEEK: The journey into the heart of the myth of cinema, in ‘The Spirit of the Beehive’ (1973). For a more extended schedule, check in here.

Andy, I’ve never seen this and didn’t know much about it, but it looks gorgeous (as Bertolucci films usually are). Adding to my list.

It really is such a beautiful film: I wish there were more high-quality stills available on the internet to help illustrate… but then again, it’s better to go and see the film itself, so perhaps it’s for the best.

Have you seen ‘Last Tango in Paris’? Perhaps Bertolucci’s other ‘masterpiece’: and again, shot with Storaro. Paris and Bernardo are a winning combination.

Thanks. I never would have known to pick this one up. I just barely finished it. Whew!

I wish I was watching this in a film class. It is begging me to write a paper. So, I am compose essays in my head. I would love to explore normal. Being normal vs. feeling normal vs. appearing to be normal. This normal idea has a very unique treatment in this film and I especially loved that, Italo, his blind friend was the one to point out to Marcello that everyone else is trying to be different.

The confession scene was my favorite for its acting and dialog. The priest is begging for details, the fiancee is giddily waiting outside. Marcello is flippantly bearing his soul in an effort to shock. I am imagining a paper in my head analyzing both his motivations or maybe just Bortolucci’s organization of the confession and blame sequences. Marcello knew absolution was always the result of confession. Though he wanted to be free of the memory or his sins he obviously didn’t believe in any sort of spiritual healing but he laid it all out there anyway. Suddenly, in the last scenes we guess that Marcello found God as we see him teaching his daughter to pray. So, when Marcello discovers that he hadn’t killed his molestor and tried to reallocate the blame on him and erase his uncomfortable memories, I think he was hoping for a transformation. And I think he was devastated that he felt unchanged. The very last camera angle on his face was tremendous. I had to rewind it to stare at his haunted demeanor. He was looking over his shoulder at a man in the streets playing music. Brilliant.

Oh, and patriotism. I am not as interested in the relationship between communISM and facsISM as I am patriotISM. I feel ill about the foreign relation affairs of my country. Years ago I might have agreed with what our goverment would have me believe. But now I am at definite odds with their actions and sanctions and war contracts. Marcello made some interesting turns and twists and turns again in regards to his relationship with his changing country. Very interesting treatments.

The film was beautiful–visually stunning. I only wished that I could care more for Marcello. I couldn’t quite empathize with him nor understand or believe the immediate and mutual attraction between him and Anna. I wonder if it is a cultural issue, my background experience or an issue of the era in which the film was made. His behaviors toward his wife, mother, father and friend were all so cold. But, I guess they were consistent.

There is so much to think about. Marcello will be in my head for a long time.

I’m so glad you watched along with us this week, Hinged! This may not be a film class, but it’s certainly a good place to share your ideas about the films.

Marcello appears to go to confessional just to please Giulia, but I think you’re right that there’s something deeper going on in that scene. He’s testing the church as an institutional apparatus – to see whether it will bend to his individual and political power. The shot seems to me to be brilliantly divided between the Priest and Marcello – and then later, with Giulia in the foreground – all these forces in the balance. When I get a chance I’m going to go back and watch for that expression at the end that you describe.

I, like you, felt little empathy for Marcello. The characters around him are so much more humane than him. The question of his attraction for Anna is a complicated one. It’s not easy to spot, but the same actress that plays Anna appears in a couple of scenes early in the film: as a prostitute, and then as the woman on the table in the large government hall. Her eyes connect with Marcello’s there: and there’s a sense of recognition when he meets Anna at the professor’s house later. It’s open to debate whether the earlier women ARE Anna, or whether Marcello has merged the experiences in his mind.

Marcello is cold: and I recognise this coldness to some extent in some of the people I know and love. When the world won’t bend to your ideal view, then what can you do? To some, a hard, cold distance is the result – a protection against the too-raw reality. As an idealist who has been exposed to much of life’s pain and violence, Marcello is colder than most.

Never seen The Conformist, but have long wanted to. I’ve seen Last Tango twice, and was underwhelmed both times. Paulene Kael loved Tango though, which makes me feel like I’m missing something. The Last Emperor hasn’t really endured, but I’ve always been fond of it. I loved The Dreamers, Bertolucci’s last film.

Ditto for me on The Last Emperor and The Dreamers. I also have an irrational fondness for Stealing Beauty (something to do with my fascination with bohemian communities and the tender realism of the sex scene at the end). I’ve only seen Last Tango once and I wasn’t wowed by it either, but I’ve been thinking I should try again — it has been years.

Matt, part of the joy of Last Tango for me was seeing Marlon Brando, up close and ad-libbing his way into what looks like some kind of window to his personality. It’s well known that the filming of that movie was made more difficult by the presence of Brando’s file card prompts all over the set… :)

Plus, it’s visually, so strong – like The Conformist. There’s that amazing scene where Brando’s character speaks to the body of his dead wife, in a dark room, the only lights on his face, and the body, surrounded by hundreds of purple flowers. Powerful.

As for the power to shock the audience, I think it still has it.

Really enjoyed this read, Andy. And great comments from everyone. Seems like a strongly humanist message in the meta. If Hinged is right about the turn to God, I’d be disappointed. I’ve not seen the film so this is from ignorance, but my suspicion is that it’s about doing what works, or at least exploring … much more than doing what’s right or objectively true.

@ Andy. I didn’t even realize Anna played the prostitute and woman on the table. You’re so observant! I totally missed that one. I’m thinking according to the time-line of the film they couldn’t have been the same person, but why not symbolically? I realize that I often look at films as a critique of how well they were done–as if I can say. I like how you allow them to stand and wander within the work not outside it. If I let it stand as a piece of art maybe Marcello was looking for the antithesis of his wife. If I think about it that way, I can better understand or believe his attraction.

Cowardice is also a great theme. Was he more of a coward in not assassinating his professor and Anna? His fellow spy compared cowards to Jews and Homosexuals. Or was he more of a coward in blaming his actions on the chauffeur and outing his friend? I still wonder.

@ Matt. Don’t be disappointed. He was simply teaching his daughter the Lord’s prayer. He was also living with his wife and all of her family during this time of government unrest. Your comment has made me pause. I wonder if we see him urging his daughter to pray in order to seek after the normal. Perhaps he thinks this will give his offspring a more normal life.

Great movie pick!