“Novelists, poets and playwrights make literature; screenwriters make changes.”

So jokes Scott Burns in a recent column titled “From Script to Screen with ‘Contagion,'” appearing in the 9-10-11 Wall Street Journal. But, in spiteof Burns, do any of you read screenplays as if they were any other form of literature? I do. And here are some of my favorites.

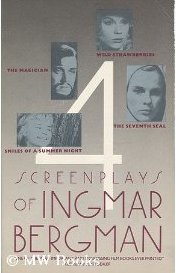

I find Ingmar Bergman’s scripts read exceptionally well as literature, standing independently from their film incarnations. I own and have read several collections of his screenwriting, each movie script as enjoyable as reading a play by Ibsen or Chekhov. In particular, I recommend the volume Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman that includes English translations of “Smiles of a Summer Night,” “The Seventh Seal,” “Wild Strawberries” and “The Magician.” Even though I have already read the subtitles while watching each of these movies, I find the act of reading Bergman’s scripts on paper a very different aesthetic experience, uncovering nuances invisible on the screen, a glimpse behind the veil at the pre-existent spirits inhabiting each movie.

The screenwriting of Bergman’s most devoted disciple, Woody Allen, also bears reading as a literary work, especially the output from his “serious” period. The publication Four Films of Woody Allen includes several of these screenplays: “Annie Hall,” “Interiors,” “Manhattan” and “Stardust Memories,” each comparable to the work of playwrights writing for Broadway at the time.

If you are serious about reading movie scripts, Faber and Faber Limited, a UK publishing house (most notable perhaps for its former editor, T. S. Eliot), is a frequent publisher of screenplays and worth browsing on Amazon.

For instance, Faber published the screenplay for one of my favorite movies, “Sex, Lies and Videotape,” by Steven Soderbergh. Anecdotally written on a legal pad during an 8 day cross country trip, SLV is a rich verbal exploration and chronicle of loneliness, sex, love and disgust.

Of course, many novelists have tried their hand at screenwriting, seemingly transferring their literary gifts to the collaborative process of script writing. Unfortunately, many of them wrote screenplays as a last resort to make ends meet. William Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald are the most prominent examples, their resultant efforts largely revealing their less than inspired cause.

Faulkner’s best scripting effort was likely working with the team that adapted Raymond Chandler’s novel, The Big Sleep, for the big screen. At one point, Faulkner was forced to call Chandler when the team was unable to determine the identity of a certain killer in the novel. Chandler, upon reflection, responded that neither could he. This clever screenplay, formatted as a shooting script, can be found here.

“The Third Man,” one of several screenplays by novelist Graham Greene, is also a personal favorite. Since Greene first wrote it first as a novella, it’s tempting to view this work derivatively, but the novella was in reality written by Greene as “cross-training” preparation for composing the screenplay, the novella being published after the movie was released.

Admittedly, most of my examples above are exceptions to the rule that scripts today are written by collaborating teams of writers, and then revised by actors and directors (and studios) on the fly. This process seems to eliminate in large part traditional notions of authorship typically equated with understanding a work as literature. For many, this alone suggests that screenwriting is not a literary endeavor, perhaps not even the activity of writing itself, but simply a part of the process of movie making, as if the writing of a screenplay were the equivalent of merely typing letters on a screen. But I find this as irrelevant to determining the literary value of a script as I find theories about multiple authorship in determining the literary worth of Homer’s poetry or the Books of Moses in the Hebrew Bible. There is only one way to test any production with claims toward literature: read it.

What screenplays have you read?

;

;

I’m actually fascinated by the idea of collaboration itself. I think we tend to idealize the lone wolf artist (Jonathan Franzen hacking away for years in his office without internet or other distractions), but I’m very interested in the messy, chaotic, but often so brilliant results of a team. Maybe this is from doing so much theater growing up, or being in bands or working on Doves, but I feel like my work is always better when it bumps up against the advice and guidance of other writers.

To answer your question though, the only screenplay I’ve read is Pulp Fiction .

Heidi, good points. “Auteurism” isn’t dead, despite Roland Barthe. And, who hasn’t produced something without the help of others? TS Eliot himself had his Ezra Pound, and, as Eliot pointed out, the individual talent cannot be understoond or explained without the long, long line of tradition upon which it inescapably draws.

Understoned, understood, same difference.

I belong to a screenwriters group in Salt Lake City so I read screenplays all the time. However, they’re usually early drafts that have yet to be produced. :-) You can find it on Facebook under “Utah Film Writers”.

Joe, I’m sure you read final (and produced) screenplays as examplars of your craft. Do you have a favorite screenplay, and why? Do you consider them literature?

I think screenplay is a new genre of literature .if drama is literature why not screenplay?after making of film screenplay not only a byproduct,if screenplay writer rewrite as reading style,it will must be literature.

Good points. Good writing will always find its way into becoming a part of our “literary” definition. Some of the best literary criticism itself is literature worthy of appreciation and interpretation. And, what of the several historical writings that are now valued more as literature than “accurate” history (Gibbon, etc)?

I will go to research about screenplay as literature or screenplay is a new genre of literature on the based Bengali literature and Bengali screen plays.please send any information or any documents.

Many of film director thinks screenplay is not a literature.they written for only cinema.after making cinema their have no necessary for director.but i think if script writer rewrite screenplay for reader it had great literary value.screen play writer change from original but we think the change had aesthetic so it will be a new genre of literature.

Thanks Manabendranath for your continued interest in this topic.

I’m about to watch Alfred Hitchcock’s “Saboteur” with my daughter (who is a Hitchcock fiend) and one of the many reasons I like this film is because Dorothy Parker contributed to the screenplay. So, much of the snappy dialogue in the movie must come from her pen, but it’s probably impossible to tease her words out of the final product. It’s odd to me that in fiction, many critics think the author is dead, but in film studies, many subscribe to “auteur theory” that says the director is the “author” of a film, François Truffaut being the critic who popularized this idea. So, Hitchcock, among others, gets the benefit of “authorship” over the final product.