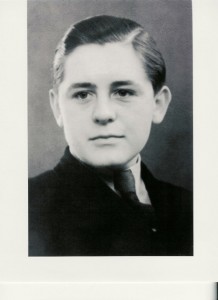

[A guest post from our friend Mark B]: This week we mark the anniversary of the death of Helmuth Gunther Huebener, a Latter-day Saint young man who was executed by the Nazi regime for treason on October 27, 1942, at the young age of 17. He is one of my favorite Mormons.

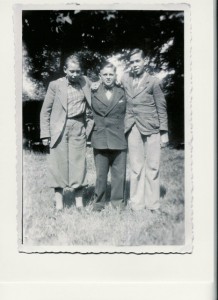

Helmuth was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1925 where he and his mother attended the Sankt Georg branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He was a personable and responsible young man who was well-liked by both his peers and adults. [On a personal note, I served a mission in Hamburg. While there, I met a few of the old-timers who remembered him and who first told me his story.] He and his close friends in the church, Rudolph (Rudi) Wobbe and Karl-Heinz Schnibbe participated in church activities and the Boy Scouts. As Nazis did away with the Boy Scout program, these boys were soon required to join the Hitler Youth. Helmuth participated in Kristallnacht, where the homes and businesses of Jewish Germans were vandalized, and it was at this time he started to question his loyalty to the Third Reich. Helmuth’s friend, Karl-Heinz, was even more rebellious, and was expelled from the Hitler Youth for punching his leader in the face. This act earns him a virtual high-five from me, across the decades, as well as a sic semper tyrannis.

In 1941, the boys gained access to a short wave radio and began listening to BBC broadcasts about the war. (At this point even the possession of a short wave radio was considered an act of treason.) They realized that the BBC reporting was different from the reports coming from the Nazi government, in particular the news about the progress of the war and the number of German casualties. These young men became official enemies of the State and genuine Nazi resistance fighters when they began transcribing the BBC broadcasts into German, printing them as leaflets, and distributing them around Hamburg, putting them in mailboxes and posting them in public places. One of Helmuth’s co-workers reported him to the SS and he was immediately arrested.

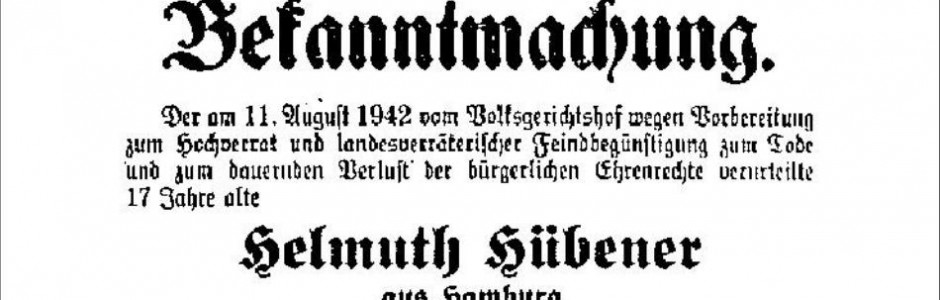

The boys understood the danger they were in and had already agreed that if one of them were caught, he would claim to have been acting alone, thus deflecting guilt from the other two. For two days after his arrest, Helmuth shielded his friends, but after intense questioning (we in the United States today might call it enhanced interrogation techniques), his questioners learned the names of his associates. Helmuth was 16 at the time, and reasoned, incorrectly it turned out, that the death penalty would not apply to him as a minor. However, he feared for his friend, Karl-Heinz, who was 17, so he told his interrogators that Schnibbe was only marginally involved. This falsehood undoubtedly saved saved Schnibbe’s life. Although his mother and local church members appealed for clemency, the Volksgericht, knows as the Blood Tribunal, sentenced this young man to death, and the sentence was carried out on October 27, 1942, in the prison at Berlin-Ploetzensee. Both Rudi and Karl-Heinz served prison sentences, and Karl-Heinz was later also imprisoned by the Soviets.

The boys understood the danger they were in and had already agreed that if one of them were caught, he would claim to have been acting alone, thus deflecting guilt from the other two. For two days after his arrest, Helmuth shielded his friends, but after intense questioning (we in the United States today might call it enhanced interrogation techniques), his questioners learned the names of his associates. Helmuth was 16 at the time, and reasoned, incorrectly it turned out, that the death penalty would not apply to him as a minor. However, he feared for his friend, Karl-Heinz, who was 17, so he told his interrogators that Schnibbe was only marginally involved. This falsehood undoubtedly saved saved Schnibbe’s life. Although his mother and local church members appealed for clemency, the Volksgericht, knows as the Blood Tribunal, sentenced this young man to death, and the sentence was carried out on October 27, 1942, in the prison at Berlin-Ploetzensee. Both Rudi and Karl-Heinz served prison sentences, and Karl-Heinz was later also imprisoned by the Soviets.

It is very painful to know that the Sankt Georg branch president was a party member who had placed a sign on the door of the meetinghouse saying “No Jews Allowed”. Although there is no record of a church court, this branch president wrote “Excommunicated” on Helmuth’s membership record. His membership was posthumously restored and his membership record was amended to say “Excommunicated by mistake”. It really hurts to know that at the time when he most needed his church community, we failed him. However, he kept his faith to the very end.

On the morning of his death, he wrote a letter to a friend in the local LDS branch which included these words: “”My Father in heaven knows that I have done nothing wrong. I know that God lives and He will be the proper judge of this matter. I look forward to seeing you in a better place.”

If I were king of the church, I would issue a decree that the story of Helmuth, Rudi, and Karl-Heinz would be studied every year, in every youth and seminary class. We talk glibly about the tension between conscience and obedience, but these young men lived it. We should also give some credit to his mother, who raised him essentially as a single parent. It must have been terribly difficult, especially in wartime, and we can only guess at her pain when her son was taken from her in such a cruelly awful way. But she clearly succeeded in teaching him bravery and loyalty. Most importantly, at a time when the majority of the adults couldn’t tell right from wrong, she somehow managed to endow him with a moral compass which pointed true north.

The story of Helmuth Huebener is better known in Germany that it is among his co-religionists. Streets and youth centers in Germany bear his name, and Gunther Grass celebrated Huebener in his novel Local Anesthesia. Newberry-award winning author Susan Campbell Bartoletti has written about Huebener twice, in her 2005 book Growing Up in Hitler’s Shadow, and in her 2008 Huebener, The Boy Who Dared.

Imagine if we studied his story at church.

I find it sad when religions fails its people but churches in Germany allowed good people to turn a blind eye.

The churches not just the lds church did not stand up to evil.

It is very sad.

WWII was an extremely difficult time for everyone. Communication between LDS Church headquarters and local wards and branches in Nazi occupied countries were almost completely severed, if not utterly. It was difficult for general leadership to maintain its method of “check and balances” on local leadership because of this. Mormons are not immune to weakness and so it is no surprise that some members supported Hitler in the beginning and got caught up in the anti-Semitism that was ravaging the minds of the populace. Obviously, while that helps us to understand why and how things happened, it does not lend a shred of excuse for anyone behaving in such a deplorable way. I can’t even comprehend the oppressive fear that everyone lived under. For those who were able to have that much decency, humanity, courage, and selflessness, to not give in to Hitler’s regime we undoubtedly applaud and give highest honor. I read about Helmuth and his friends in “Three Against Hitler” as a teenager and was deeply touched. I decided that you haven’t lost if you’ve maintained your honor til the end, even if you have to die for it.

I think our boys would gain a lot of knowledge by hearing this heroic story. I don’t care who you are and what you get “caught” up in, there is a moral compass inside us that tells us what is right and wrong, whether we are religious or not. The church has been very quiet about these stories and I would like to hear more of them but perhaps they’re afraid of what church leaders/members did back during that time.

Well done, Mark B. What an important reminder of real integrity. Heubner’s story wrenches my heart every time I hear about it. Has anyone read Bartoletti’s books? Or Grass’s book?

It’s difficult to judge someone who decided to survive Hitler’s Germany by being quiet, protecting themselves and their family. I don’t. A parent with small children has an obligation to protect them. Someone who actively perpetrated heinous acts under the guise of patriotism, however, is different situation. Most LDS in WWII Germany seemed like the quiet survivor type. And celebrating Huebner’s heroism does not place judgment on those who chose that path. There is Book of Mormon precedent for a situation like this, when Mormon, leader of his people’s army, refused to support them when their cause became unjust:

“And it came to pass that I, Mormon, did utterly refuse from this time forth to be a commander and a leader of this people, because of their wickedness and abomination (Mormon 3:11).”

I love Helmuth Huebener! I was flabbergasted and honored to learn of his life and death when I was a student at Heidelberg Universitat, my junior year study abroad. That same year my 85-year old Tante Lydia told me, while watching the New Year’s Eve fireworks in Schwabish Gmund, that she had indeed voted for Hitler. Such a complicated national history. I would vote for you for king of the church, just so that we could implement your idea to honor Helmuth, his 2 friends and his mother. Thank heavens that the church reinstated his membership. May we all live fearlessly like Helmuth.

I first learned about Helmuth Huebener when I was 13 and read the fictionalized account of his life, “Brothers In Valor”. I had wanted to read it because it was a WWII story, but had no idea he was LDS. His story shocked and touched me, and since then he and his comrades have been an example I strove to model my life after. He was a truly great young man.