[A few weeks ago, Heather wrote a lovely piece explaining how and why she has held on to Mormonism. Here, in a belated response, I explain why I have not.]

Let me tell you about the Mormonism of my youth.

I was born in the early 1980s, to a house steeped in the science fiction of the 60s and 70s. The Alan Parsons Project spun on the turntable, Frank Herbert sat on the bookshelf, and Star Trek and the Twilight Zone played on the television. As an early teen I watched The Next Generation with my father. We compared and contrasted the quasi-gods of the Q continuum with the naturalistic, contingent God of Mormonism. Our conversations would frequently devolve into gleeful riffs on the cosmic truths dispensed by Joseph Smith. Could a damned intelligence be reorganized into new spirit bodies, as Brigham Young and John Witdsoe conjectured, or were sons of perdition consigned to eternal separation from God? More frivolously: Could a celestial sword cut off the arm of a resurrected body?

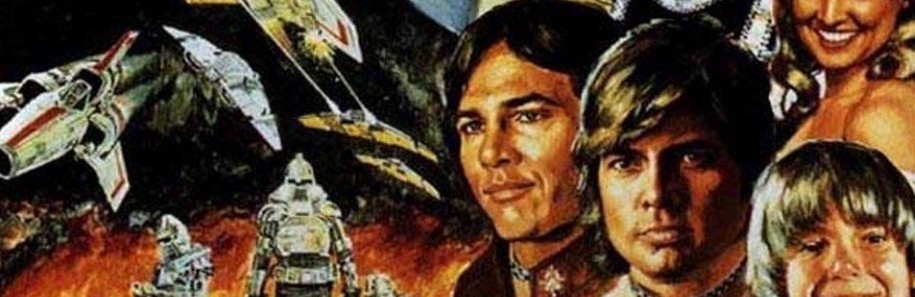

My Mormonism, then, was a Mormonism of ideas. Big, cosmic, even (quasi-)scientific ideas. It was a Mormonism that inspired Parley Pratt’s speculative fiction, Battlestar Galactica, and the novels of Orson Scott Card. A Mormonism that propounded rough outlines of a cosmogony and a metaphysical dynamics, that decreed laws so unbreakable that God himself couldn’t break them. It was a Mormonism that taught me about the universe and what it means to exist — as an uncreated and independent agent — in it.

My Mormonism, then, was a Mormonism of ideas. Big, cosmic, even (quasi-)scientific ideas. It was a Mormonism that inspired Parley Pratt’s speculative fiction, Battlestar Galactica, and the novels of Orson Scott Card. A Mormonism that propounded rough outlines of a cosmogony and a metaphysical dynamics, that decreed laws so unbreakable that God himself couldn’t break them. It was a Mormonism that taught me about the universe and what it means to exist — as an uncreated and independent agent — in it.

But it was also a Mormonism of knowledge. Our speculations on intelligences and agents weren’t enjoyable merely as an intellectual exercise, but as an exploration of the logical consequences of a few eternal truths. They were satisfying because they were founded on ideas we knew to be true. My Mormonism was strong on Moroni’s promise: One could know with certainty the truth of its precepts. And one had better know; Mormonism was too outrageous merely to be hoped for or taken on faith. I spent my late teen years, including the first few months of my mission, chasing that certainty, seeking and finding the sureness that made my Mormonism worthwhile.

So when I lost that sureness, there wasn’t much left to hang on to.

We could have a long conversation about the specifics, but you’ve probably heard it all before. We could go the rounds on Mesoamerican and Biblical archaeology, textual criticism, funerary papyri, doctored revelations, and suppressed historical inconveniences. We could debate the merits and reliability of spiritual sense experience as an indicator of objective reality. The short version is that I no longer trust my spiritual senses, and I judge that the evidence — in the usual sense — rules out Mormonism as I believed in it.

Of course, there’s nothing intrinsic about Mormonism as I believed in it. There are as many Mormonisms as there are (former) Mormons. And I see among them Mormonisms capable of weathering the storm that shattered my faith.

I see the historian’s Mormonism — the Mormonism of Leonard Arrington or Armand Mauss. It admits outright that the stories we heard in Seminary or read in our lesson manuals and official histories are false or oversimplified. It’s a Mormonism that did not unfold according to a tidy, obviously-miraculous narrative, but in a messy, human process — so human, in fact, that the hand of God is barely discernable. The Book of Mormon may be riddled with 19th century artifacts, this Mormonism admits, but somewhere in there is a kernel of historicity. The church may progress in a manner nearly indistinguishable from any other human organization, but somewhere in there is God leading His church.

But I can’t believe in that Mormonism. Again we could bicker about the details. We could talk of null hypotheses and burdens of proof, of positivism and falsifiability, of probability and plausibility. But ultimately this is a Mormonism for which its being true is indistinguishable, with respect to the evidence, from its being false. It’s a Mormonism that makes few observable predictions, in other words, and I can’t believe in something so far-reaching without positive evidentiary support. I admit that this position is fraught — there are countless other approaches to knowledge as well-founded as mine — but I have to hang my epistemological hat somewhere. I need a Mormonism I can know, not merely hope for.

I also see the theologian’s Mormonism — the Mormonism of Dan Wotherspoon or Jana Riess. This Mormonism isn’t terribly concerned with the facticity of the truth claims. It doesn’t matter whether the Book of Mormon is a historical record, or whether Joseph restored ancient ordinances in revealing the Endowment. What matters is that the theology point to larger, pluralistic truths that transcend culture and creed. The divine — interpreted broadly — uses this Mormonism alongside other religious traditions to teach humanity of our commonality and connectedness.

I also see the theologian’s Mormonism — the Mormonism of Dan Wotherspoon or Jana Riess. This Mormonism isn’t terribly concerned with the facticity of the truth claims. It doesn’t matter whether the Book of Mormon is a historical record, or whether Joseph restored ancient ordinances in revealing the Endowment. What matters is that the theology point to larger, pluralistic truths that transcend culture and creed. The divine — interpreted broadly — uses this Mormonism alongside other religious traditions to teach humanity of our commonality and connectedness.

But I can’t give myself to this Mormonism. One last time, we could argue. We could discuss Fowler’s Stages of Faith or Campbell’s The Power of Myth. You might cite William James’s pragmatism, reminding me that “truth is what works.” But it wouldn’t change the fact that this Mormonism doesn’t scratch the soulful itch of my old Mormonism. Its ideas are universal, and they are worthwhile, but they are also nebulous. Following them might make me a better person, but they don’t convey tangible truths about the universe or about myself — at least, no truths I couldn’t learn somewhere else.

I see the Mormonisms you are building, and I admire them. They are ambitious and thoughtful. But they are also foreign to me. They no more speak to my soul than does Lutheranism or Buddhism, and I can no more convert to them than I can to any other faith. It’s not that I’m immature or captive to black-and-white thinking. I see the complexity; I see the nuance. But I do not find it compelling.

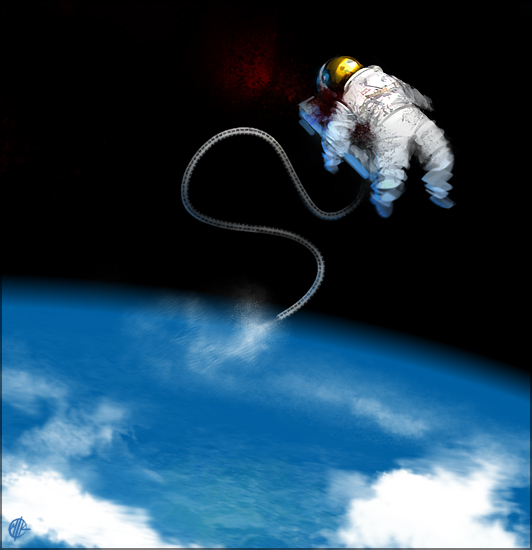

So I’ve let go. Yes, I entered free fall. But it was not a terrestrial fall, hurtling me to the earth at terminal velocity. It was the weightless fall of outer space — as cosmic as the Mormonism I once believed in — drifting me gently, comfortably toward no destination at all.

Matthew…thank you so much for these words. I find myself in the middle of defining what Mormonism is to me. At this point I have not let go completely, but I’m hanging on by a thread

Excellent post. I identify with a lot of it.

Matthew,

I appreciate this essay, for its honesty and mere existence. I get tired of hearing the trite predictions of apostasy through sin. No one who separates themselves from the church that I have personally known has fit that negative, narrow causality and we as a people need to stop vilifying those who separate; nothing assures the permanence or hurt of those who leave, than concerted prejudice.

I suppose I fit somewhere into the ideas above, but what tethers me to the church is that the God I believe in will always remove evidentiary proofs which would “box” us into beliefs/performances by a process that may be used upon/against another person. In fact, I think that the real faith experiences are always personal – that which converts us will convert only us. I’ve thought that this is a protection of the “designer” of our mortal experience, a safety put in place so that those that believe cannot present externally-validated truths as a lever to force unbelievers into compliance. It is the Free Agency Assurance Program. “)

Great comment. I would love to hear more of your thoughts on this concept.

Matthew, thank you for articulating this so poignantly. Like Garrett, I am still defining my Mormonism but I can identify with the various types you outlined in your post. Thank you again for sharing.

This is great.

Well said Matthew. It seems like another type of Mormonism that many people understandably cling to after losing orthodox faith is cultural Mormonism. Whether if it is the green jello, the opportunities to serve, the communal framework, or accepting the Church for its beneficial teachings, many people hold to the pragmatic goodness within the Church and make that their Mormonism. Of course the big questions are, first, whether or not one can access the pragmatic goodness of the Church when one does not fully subscribe to the religious narrative (which seems to be the umpf that keeps the pragmatic goodness going), and second, if the harm done by the Church outweighs its pragmatic goodness.

Right, and cultural Mormonism was a complete non-starter for me. In general I was *opposed* to Mormon culture. I was so wrapped up in the ideas that jello and FHE and reverent meetings were at best boring distractions from the real stuff.

But I don’t quibble with anyone for whom the cultural aspects are enough reason to stay. I’m willing to accept that religion is primarily about meeting people’s needs, and I’m willing to trust (most) people’s ability to work out the consequentialist arithmetic for themselves. I’ve had people tell me I’ll care more about the cultural component when I’m older — I’m 30, married, with no kids — and they may turn out to be exactly right.

Yeah, I totally get that, now more than ever. However before adulthood, at least for me, LDS culture was everything. I know LDS culture is simplistic, corny, and shallow, but dammit, so was I and I loved it. As someone with few friends in high school, my social network was based in mutual and church. I loved going to seminary and hearing the teacher speak in a hushed voice some secret truth. I loved watching God’s Army and the Singles Ward over and over again and seeing my future self healing people and knocking on doors all while having some good clean fun. I loved the monthly camp-outs and the awkward stake dances. I loved the feeling that I was chosen and that I was the actor in some big epic narrative. I loved the interactions I had with adult leaders with their cool confidence and genuine concern. I loved looking forward to a mission and I loved my mission. I loved the simplicity of it all. I knew what I needed to do and there was no question about it. Sure, there was the sexual shame that did cause some unnecessary psychological pain and I always felt guilty for not having that “burning in the bosom” experience, but man, I just loved the correlated cultural Mormonism that I grew up with.

Now, the foundations of the narrative have crumbled. What was once meaningful is now offensive and boring. What use to be valued friendships have been exposed to run only as deep as my ability to toe the party line. It has been years since I have found that same meaning in the Church and I find myself running on the fumes of nostalgia of what once was. I am trying so hard to access those benefits, but without the shared acceptance of the narrative, I’m not sure if that will ever be possible.

JohnE,

Wow! Your comment really struck home with me. I completely identify with what you said.

Matt,

Brilliant. Thanks for sharing.

Good. Stuff.

Bullseye

Matt,

I like your discussion of the different ways to believe without actually believing. And I can totally relate to the Mormonism you grew up with. In my family, the eternal truths were regarded as just as important, and reliable, as scientific principles, and I always thought they existed in harmony, side by side.

Bravo!

Matthew,

Really wonderful essay. Thank you! I also appreciate the shout out (and to be in the company of Jana Riess) regarding a theological Mormonism!

Hope it’s okay to say that I don’t find myself all that well articulated in what I think you are saying about my position. I relate to the first bit more than the second: This Mormonism isn’t terribly concerned with the facticity of the truth claims. It doesn’t matter whether the Book of Mormon is a historical record, or whether Joseph restored ancient ordinances in revealing the Endowment. What matters is that the theology point to larger, pluralistic truths that transcend culture and creed. The divine – interpreted broadly – uses this Mormonism alongside other religious traditions to teach humanity of our commonality and connectedness.

Up until the end of the Endowment sentence, I can live with. But I actually don’t consider myself a pluralist in the sense you speak of. What transcends culture and creed for me are not “pluralistic truths” in the sense of specific ideas or claims (sure, I kind of like the perrennial philosphy and maps about causal, subtle, material, etc.) but those are all secondary sorts of things. Rather what matters to me is Mormonism’s ability, like that of other traditions, to point toward experiences and embodiment of connecting/expanding energies. In the famous Buddhist statement about not mistaking the finger that points toward the moon as the moon itself has next to nothing to do with “truth” (the moon isn’t something primarily to be thought about) but rather “experience.” When in the areas where religions and spiritual practices play (or at least value, since some are pretty pathetic), words/ideas will always fail. Even experience is never fully unmediated, but they ARE powerful and transformative.

So where do ideas and things religions like Mormonism fit in? For me, practices and sets of ideas that lie at the core of religions can help us both desire and achieve experiential knowing, but once that immersion in causal and unitive and “full” realms is tasted and has begun to be known/affect one’s core sense of the universe, these ideas and rituals naturally fade and are seen for what they are: better or worse “pointers.”

I personally think Mormon scripture has wonderful pointers and wonderful examples of people who chose to actually dive and seek for themselves. It encourages us to meet God ourselves/become Gods ourselves. It has ideas about the eternal nature of human beings–uncreated, actual entities that are identical/continuous with the “cosmic stuff”–that are exciting to me and have made me want to take the dive. So I have, and I’m glad for it. From these dives, I feel grounded and oriented in something real far beyond any teaching or concept. I’m far from done, but most of the time I feel a sense of something good happening “in” me, and I want to keep going…

You continue:

But I can’t give myself to this Mormonism. One last time, we could argue. We could discuss Fowler’s Stages of Faith or Campbell’s The Power of Myth. You might cite William James’s pragmatism, reminding me that “truth is what works.” But it wouldn’t change the fact that this Mormonism doesn’t scratch the soulful itch of my old Mormonism. Its ideas are universal, and they are worthwhile, but they are also nebulous. Following them might make me a better person, but they don’t convey tangible truths about the universe or about myself – at least, no truths I couldn’t learn somewhere else.

I reply: You CAN learn these kinds of truths elsewhere. You can also learn them in Mormonism. But no one will ever learn them focusing still in ideas and worrying about whether this or that person ever lived or if this myth at some point loses its way or if this teacher eventually shows just too much humanness. To truly learn a truth, it must be experienced. I don’t break through often, but when I have and do (and even when I have the more regular kind of break throughs in seeing a person and their beauty and learning to love them despite the fact that they are speaking and acting more from fear than faith) it never feels nebulous. These are the most concrete, partciluar experiences of my life for they have become part of me–the best parts of me.

Sorry for the ramble. Excited for a discussion if you want to have one.

Dan, you know I’m always happy to engage. And I’m sorry if I’ve mischaracterized you. Hopefully you’ll trust me when I say it’s not intentional, and it’s *certainly* not to denigrate or weaken your position. I am, however, having a little trouble pinpointing your objection. I certainly didn’t have space to give your approach justice, but I’m not sure where the little taste I’ve given contradicts what you’ve said.

It seems what you don’t like is the phrase “pluralistic truths”. I don’t mean these truths to be yet another set of factual claims, but to be truths “bigger” than any group’s fact claims. When I read your comments about “connecting/expanding energies,” I see exactly the kinds of truths I had in mind. Perhaps you’d feel it more accurate if I said that the theology points towards experiences rather than deeper truths? Maybe this is mostly a semantical disagreement.

You write:

I don’t disagree with anything you’ve written here. But the question remains: Is it better for one who has lost faith in the usual instantiation of the truth claims to learn these higher truths (or have these higher experiences) within Mormonism, or is it better for him/her to do so elsewhere? Surely the answer depends on the individual. Maybe I’m too recently burned my my lost faith, or maybe I’m too young, or maybe even I’m still too hung up on the factual, but for me and for now, I’m more comfortable seeking them outside the institution, and by and large outside the faith tradition. I’m happy to encourage those who have had different paths or who have different priorities to decide otherwise, of course; I don’t believe in a one-size-fits all path.

Matthew, I really enjoyed your post. Really captured much of my own experience. I relate to the notion of not having “a place to hang my epistemological hat.”

My Mormonism went through all kinds of phases, and was often a struggle, and there was value in the struggle. As time went on, I think I developed a faith more akin to a Bushman, Arrington, Barlow, and the like. All pretty nuanced, but comfortable. It’s not supposed to be easy, right? You’re supposed to have to wrestle with it, right? The truth hurts sometimes, right?

At a point during my study of post-Joseph Smith Mormon history and church leadership, I had an unpleasant realization: “Hey, these guys (the prophets/leaders) are terrible stewards of the doctrine! How can I trust my spiritual sensibilities, when I see such fallibility in theirs?”

At about that same time, I began to believe that Mormonism was not so different from just about every other religion, and no longer credible enough to be compelling to me. Couldn’t give myself too it any longer.

Great essay. Thanks for sharing your evolution. It resonates with me. I must add however, that I’ve let go, but part of it is still there. I let go, but mormonism is where I started my moral foundation so it still accompanies me in my free fall through space. I am no longer mormon, but my view of morality, and my view of the universe, and my view of spirituality is still hugely impacted by that foundation. I let the (mormon) chaff blow away with the wind, but I definitely kept some wheat. Perhaps the wheat I kept is the part of mormonism that is universal (not specifically mormon), but I aquired it via that mormon experience.

This gave a powerful voice to how I feel about the Mormonism I thought I used to have. I was raised with a testimony of ideas and knowledge, theology and practice. Mormons have been gifted with revelation, the gift of the whole truth, the gift of additional scriptures, the gift of authoritative leadership that has access to knowledge directly from the divine. Those poor Protestants and confused Catholics were wandering out in the darkness away from the straightness and firmness of the Iron Rod. They didn’t even know they were lost, but I did. I was given the gift of being raised in God’s church.

Mine was not the religion of a personal relationship with Jesus. Jesus was not my buddy, and God was not my dad. Jesus was my leader, and God was my father. It was not an emotional and experiential process that formed the cornerstone of Mormonism for me. Those selfless pioneers didn’t trek across the horror of land burdened with winter so I could maintenance a transformative feeling or live through life seeking embodied knowledge through some experiential process.

No! That stuff is for Pentacostals and like-minded charistmatic evangelicals. Joseph Smith specifically squashed the speaking of tongues and widespread personal revelation because it led to disorder and confusion. Charismatics had to go. They disrupt the work, the order, and the clarity of existence. God was here to organize again what man (with the help of Satan) had messed up in laziness, ignorance, and selfishness.

Joseph Smith was the Moses that liberated 19th-century Protestantism from the wilderness wanderings of the corrupted liturgy of the high church (infant baptism anyone?) and the chaotic meandering of the low church congregationalism (gotta have real authority). He pointed out the pharoah (the Roman Catholic Church) that polluted the traditions of Abraham (the primitive church) with pagan worship, and he brought us to the promised land: Zion, Kirtland, Independence, the great Navuoo, and the great Salt Lake City. Zion is a place as real as the wife I would marry, as real as the children I would bear, and as real as the ground under my feet.

We were building Zion one baptism at a time, one Sunday lesson at a time, one childbirth at a time, and one priesthood ordinance at a time. We were not living for experience and feeling. We were living as an instrument in the hands of God. We were doing his work. We were out in the field: the battle field. We were his army. We were constructing his kingdom, not nurturing a divine relationship. God was already in our midst. God doesn’t need sappy children. He needs worker bees to keep up and grow the beehive.

This Mormonism motivated me. It gave me purpose and direction that I could explain on the chalkboard of a whitewashed cinderblock church building. The feelings and experiences were the fruits and evidences of my labors, my devotion, and my increased understanding. These emotional experiences were not the source of truth or the source of testimony. I didn’t go to church to feel the truth. I went to live and learn the truth.

This Mormon neo-orthodoxy is a fascinating movement that seems totally alien to me. It is totally uncomfortable to me. It is the very wandering and confused movement of Protestantism that Joseph Smith by the hand of God clearly intended to replace with his One True Church. Now we need to nuture an emotional testimony based on experince or by bearing it over and over again? Now we are saved by Grace “despite” what we do? Now we grow Zion in our hearts and our minds instead of building a real Zion where our hearts and minds can take up residence?

Now our prophets don’t bring us prophesies and revelations. They bring us proclamations, policy changes, and talk about the minutiae of pierced ears, too much time on facebook, and disrupting the congregation to have them follow along in their scriptures. Now Jesus won’t becoming until after I’m a grandpa (thanks for the heads-up President Packer). They site scientific studies and court cases (I’m talking about you, Oaks) instead of talking as though they communed with God in the temple last week.

In Mormonism, body and spirit were the same. The temporal and spiritual were the same. The physical and the spiritual were united. Now, we have lost this unity. All that is left is a ghost of a determined and motivated movement. The spirit remains, but the body is limp. The ward buildings are hollow carcuses of a church turned into a religious institution. A religious institution that is so financially sucessful that it hardly needs its members. The corporation has its intellectual property, its trademarks, and its businesses to sustain it. The head has said it has no need of the rest of the body. All that is left of the religion I loved and lived is a memory. I don’t recognize most of what I see today as what I grew up with. It is something else. It is something that I can’t and don’t believe in anymore.

I needed a new conversion to stick with this new religion. And it hasn’t come yet. I like the old way of seeking things I know are true. Call me old-fashioned, and call me stubborn. All this new fuzzy wishy-washy stuff doesn’t seem worth my time when there is so much other stuff that seems so much closer and so much more real to me.

Wow, what a beautiful and powerful comment. Sure you don’t want to write the posts from now on? :)

This reminds me of Joanna Brooks’ article, Why is Huntsman’s Mormonism “Tough to Define”?:

This aspect of Mormonism (that there may be more than one Mormonism) seems to be in a bit of flux across the Church lately, and while any change may bring new individuals into the Church’s arms that were previously excluded, it is bound to push others out.

Great, thought-provoking piece. Thanks, Matt.

Hi Matt,

Sorry didn’t reply more quickly. We recorded a new Mormon Matters last night and I was too beat afterward to do anything.

I guess your post about your own experiences and journey and then description of my approach felt a little too “heady” to me and not as fully embodied as where I think real “knowing” is grounded (especially as transcendent kinds of knowings are ineffable). So, in that way, it doesn’t feel like semantic differences to me, but quite substantively different. I read your post as focusing most on animating ideas and how when the intriguing and motivating parts started to fall apart and no longer match well some of the literalness or historicity of scripture or the cleanness of trusting prophets and revelatory processes (including your own) things began to shake loose and Mormonism became less compelling. And, of course, all those things happened to me, as well. I LOVED, as both you and Jacob wax wonderfully about, having the “answers” and fitting it all into a story, and having a way of fitting all of my spiritual experiences and sensory experiences and intellectual experiences into “Reality” itself. All of that crashed and burned for me, as well, and perhaps it’s just fortunate that I was formally studying religion full time and that previous to all of this I’d had some really bottom-dropping-out, blow my paradigms away kind of spiritual/mystical experiences in my background, so when this loss of certainty in ideas being the “moon” came along, I kind of “got it” perhaps more easily than most that the heart of religion is the experiences of transcendence (transcending our bodies and minds, not so fully identifying with what we see/encounter via our senses or make sense of primarily through intellectual processes) and not the ideas or words or messengers with special powers. Then, over the course of the next ten years or so, I grew more and more confidence in the things I had touched and was occasionally feeling/experiencing even during this time of upheaval and sorting, and soon these became my grounding and the poles around which I oriented. And then, certainly during to some part as well, I could easily see that these things I felt confidence in were deeply embedded in Mormonism–that, indeed, it spoke very well to them, and certain parts superlatively well–and life as a Mormon became roomy and very satisfying to me again. But, again, the key is it wasn’t primarily a “head” journey for me, but an experiential one.

The last part of your response goes: “Is it better for one who has lost faith in the usual instantiation of the truth claims to learn these higher truths (or have these higher experiences) within Mormonism, or is it better for him/her to do so elsewhere? Surely the answer depends on the individual. Maybe I’m too recently burned my my lost faith, or maybe I’m too young, or maybe even I’m still too hung up on the factual, but for me and for now, I’m more comfortable seeking them outside the institution, and by and large outside the faith tradition. I’m happy to encourage those who have had different paths or who have different priorities to decide otherwise, of course; I don’t believe in a one-size-fits all path.”

I think it’s fine to seek whereever–as long as that search is not just intellectual (wrong tools, if the only ones being used, for getting at the genuine heart of religion). My strong sense is that most of us would prefer to seek within the religion in which we were raised, that is our spiritual language, etc., so for those reasons I think it’s generally more fruitful to urge people to look deeper within their own tradition, see what the Robertses, Browns, Hankses, Bennions, Englands, and others who fully engage heads and spirits and practice religion (rituals as well as service and all the things that lead to us confronting mirrors we’d often rather not face) and have discovered within the tradition rather than seeking outside it. Mormon resources are rich and wonderful (Jacob’s and you posts, again, were fantastic), and I find that they are easy to spot when we have gained our own spiritual confidence and can judge when interacting with the church what’s profound and what’s a few levels away from the real fire, what has the ring of prophetic truth versus what is administrative bluster and panic. So, if nothing else, I guess I’m just a voice for really taking seriously the calls of our scripture and key figures and coming to know things for ourselves rather than thinking that the kind of Mormonism that was all about words and teachings and correspondence match-ups.

Hi Dan, sorry for the delayed response. I’m trying to get my PhD thesis fully drafted this month, and I really should probably spend as much time away from the blogs as possible!

I’m also just not entirely sure how to respond, since I feel like we’re talking to each other across a great gulf, or speaking different languages. Despite lots of (I hope!) mutual respect, I don’t think either of us quite gets what makes the other tick.

Nevertheless, every time we interact I’m encouraged to take another step back from my epistemology-centered grounding, reevaluate my priorities, and explore giving more weight to the experiential. Am I ready to do that within the framework of Mormonism or religion in general? Mostly not, although of course my efforts are informed by Mormonism and its theological resources. And perhaps I never will be. I’m pretty passionate about knowing stuff, and I may never have an epistemological-experiential alignment that leads me back to my religious tradition. But even though I don’t/can’t/refuse/etc. to take on your approach carte blanche, don’t think you aren’t having an effect on my worldview. Because you are.

Dude, get that dissertation done! Congrats on being so close!

Back at you on your influence on me. Love our deep dives when we get together, and even when not able to go hard at it face to face, there’s always “Matthew Nokelby” as an imaginary interlocutor in the back of my mind as I write and speak. Admire you a ton.

I don’t know that anyone that is an “Internet Mormon” has not come away from the Bloggernacle, Mormon Matters, Mormon Stories and FAIR scenes without having their Mormonism transformed, sometimes in fundamental ways. I think that you however have made a choice to not trust the spirit. I don’t mean to sound better than anyone else, but throughout this whole thing where I have been transformed, I didn’t come out of this knowing that my Mormonism from my youth was not true. I came out of it knowing that it was only an approximation of truth in the first place, and that the Holy Ghost was there for me to slowly come to a knowledge of the truth through personal growth. Through pragmatic experience, I know experientially that the Church was never true in the sense of conveying to me what I will call deep or technical truth. It was only meant to be a vehicle to get me to conversion. The Church only gets Institutional Revelation to do what it has to do. The deep and technical truths come here a little and there a little, being themselves only approximations at any particular point in time. So, to be blunt, by not trusting the spirit and your spiritual faculties, you have thrown away your anchor, and thereby your ability to truly mature in the faith. Your mistake is to misinterpret the testimony of your youth as something that transmitted absolute truth to you, rather than being inspiration to get you on the path of true enlightenment. This is what I know experientially and pragmatically after my experiences with Internet Mormonism, rather than having it taught to me by anyone, especially not by New Order Mormons or Post Mormons or even Apologists trying to get me to explain away facts. The answer is not in apologetics, theology, or New Order Mormonism or any other Mormonisms that have been constructed, or even in facts at all as we perceive them even by science, not to dispense with that knowledge, but to put it in its proper order of priority. It is simply the Gift of the Holy Ghost and clinging to it, and having simple faith in it, sacrificing your whole soul to give yourself entirely over to that, in spite of all else, the simple trust that that power can and will still can guide us.

Ed, thanks for your response. I imagine that we’re simply coming from orthogonal paradigms, so it’s unlikely that we’re going to manage much mutual understanding, but let me respond as briefly and clearly as I can to your main point.

“I think that you however have made a choice to not trust the spirit.”

I’d put it a little differently: I’ve come to the conclusion that what I previously took to be the spirit is likely nothing more — and nothing less! — than a product of my subconscious. The “nothing less” is significant; I value and seek after the transcendental, and the products of my subconscious can be valuable and even vital. But I don’t see any evidence that my transcendental experiences say much about Mormonism, and I see quite a lot of evidence to the contrary. I realize that there are lots of smart people who see this differently than I do, and you seem to be among them. I respect and validate their (and your) pursuit of what they believe and know and experience, and for all I know they’ve got it right and I’m way off. But I can only do the best *I* know how in pursuing belief and knowledge and experience. And, right here and right now, this is the best I know how.

Matthew, yes, precisely. You have chosen to interpret the spirit and explain it away in such a way that you are no longer self-sacrificing your whole soul over to it and accepting it for what it is, and by not having that that faith and living as if it is so, you have closed the door by which it operates on you and transforms you. It is the indicator, or signpost of the way, not the proof. It is like the North Star The proof is an eventual Second Comforter experience, and it opens up to you through no other way than that which you are unwilling to open yourself back up to. The best way you know how is to trust what you knew from your youth, not the wisdom you think you know now. A three year old in primary has more wisdom in this matter than Dawkins does any day. I would rather sing Book of Mormon stories with my kids than sit there and listen to sour puss Dawkins attack Brandon Flowers for giving himself over to the Holy Ghost. You want the proof? Do what the Brother of Jared did, and you will have it in its natural course of events, but only as you are found being constant, not setting any time limits on it yourself, until the day comes when the Son of God opens the veil to you. You seem to be a man in search of evidence. Its odd that you wouldn’t follow the sign-post leading to it.

It’s adorable to see strangers on the internet assume to know how much faith I have or haven’t exercised.

Carry on, oh internet; carry on.

Clever!

My friend, it is *you* that have said you no longer have faith in Mormonism. I don’t have to *assume* anything about your faith. You have “let go” and no longer have faith. That’s your word.

Ed, isn’t that just begging the question? One must believe to believe? As Matt stated, you really have no idea about the faith he has exercised on his path to his current frame of mind.

This converted TO (instead of WITH or BY) the spirit business is a part of the Mormon neo-orthodoxy that I am uncomfortable with. The spirit for me as a Mormon was one of many evidences that something was true. Now it seems to have evolved into the fulcrum of truth and faith in LDS teaching.

For someone who is serious about defining a personal functional epistemology, this near wholly dependence on the spirit is defensible only in the sense that it is non-falsifiable. If your personal experince and relationship with the spirit is the cornerstone of your conviction for your beliefs and knowledge, then there is nothing anyone or anything can do to denigrate, reform, or inform your position. Your justification is completely internalized because each person has their own experiences with the spirit. A survey of the world will show that these experiences are not consistent, and they often do not correspond with a shared external reality.

In short, leaning on the spirit for your worldview is no different than what billions of other people out there in the world also do, and they don’t even come near to the same conclusions that LDS members do. What percentage of the world population is LDS or will ever be LDS? The LDS epistomology that is based primarily on the spirit is therefore unreliable. If Ed Goble’s comment about Dawkins approach being inferior compared to the three-year-old child has any value, it is to point out a serious predicament for three-year-olds. If we all just stuck with what we knew as youth, we would all just stick with the religion and worldview given to us by our parental guardians. This is perfect if you are Mormon, but it would not work out well for those who were not born in the church that God personal setup on the Earth. My faith is that there is a better way for us to know the truth.

I’m totally not saying that you cannot construct a reliable and consistent model of truth within the framework of the contemporary LDS faith. I just think that the over-dependence on the argument from spiritual experiences is an excuse that has grown out of a missionary-driven organization that has become impatient and weary of defending itself on the same plane as contemporary thought. And, I think it is mostly a modern phenomenon in the LDS faith. LDS apologetics has largely moved to a position of defending the tradition from a completely different perspective than what modern thought operates on. It is a safer place. Whereas Mormonism of the past was trying to stay right up there with the best of growing human knowledge about world history, geography, astronomy, linguistics, athropology, etc. It seems to have given up on that mostly. I think Dan Peterson being let go is a sign of this transition.

My personal feeling is that I wish I had learned about epistemology before I went on a mission.

Good points, Jacob. My reply would aim mostly at the consistent use of “the” in front of “spirit” in your post, and then your seeming to indicate a focus elsewhere, as well, on LDS views of spirit rather than engaging the idea of different, wider connections with Spirit , which leads one to recognize confluences with core sensibilities of other traditions while still not going where some in this thread have that it all of these encounters with Spirit are essentially “the same.” If ask, I am happy to post some charts, etc., where mystics and students of such things note a dozen or more “types” of experience. LDS notions (at least as typically discussed) about the Holy Ghost, Light of Christ, Spirit of God, etc., all have some resonance with at least some of what’s been described by others, but come nowhere close to exhausting the range. Plus categories themselves break down (if not completely at least in terms of recognizing that nothing that can be described can capture the experience) in the midst of encounters with Spirit.

And, of course, the problem of private interpretation is a perennial one (one of the major areas of philosophy of religion), with no theories really ever able to fully satisfy–and how could on, anyway? Impossible task. In the end, all one can do is share about them and tell stories about the practices or states of being that preceded them (maybe articulated in terms of spiritual disciplines), and invite others to try the experiments for themselves. Sometimes what one says will feel familiar or resonate with another who has experienced something similar. We then hear their stories and about their practices, perhaps try them, and occasionally in doing so we’ll capture new aspects/flavors and become even more convinced about Spirit and ourselves. On and on when it yields good fruit. (Starting to sound a lot like Alma 32, so I’ll quit before you throw your computer across the room!)

In Adam Miller’s Rube Goldberg Machines he has an essay called The Gospel as an Earthen Vessel where he says

Hi Carey, can you provide a link? I wasn’t able to find the original.

Matthew, thank you so much for this essay. It describes perfectly how I feel about the other Mormonisms that various people subscribe to (my wife is one of those people). I respect and at times envy those who can make Mormonism work within their new nuanced worldviews, but reading the comments from Dan Wotherspoon makes it clear to me that on a fundamental level, I just don’t grok those ways of thinking about it. I never had anything remotely approaching “really bottom-dropping-out, blow my paradigms away kind of spiritual/mystical experiences.” I did have answers to prayers in the form of feelings of peace, goosebumps and burnings in the bosom. And that was enough for me, because that was all that I was taught to expect. If God wanted to give me more I was always open to it, but I never sought after more powerful experiences because that would be sign-seeking, and thus sinful.