Welcome to the first installment of our summer book club reviews. See the rest of our reading list here.

Carrying the Fire

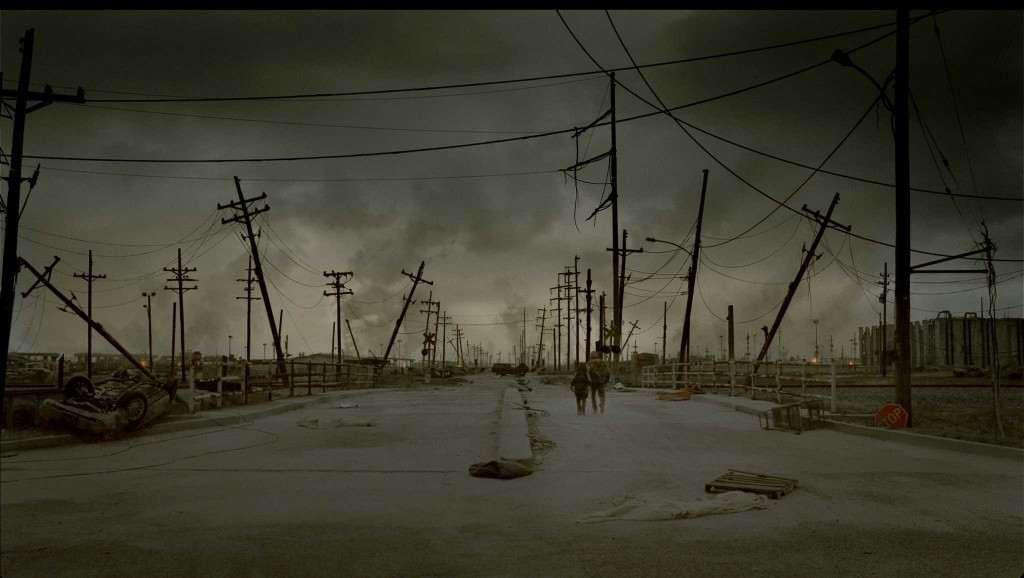

Cormac McCarthy’s The Road begins in the woods at night. An unnamed man awakens from a troubling dream and reaches to touch his young son, to feel the rise and fall of ”each precious breath.” The man knows they will not survive another winter in the north and so they are heading south, pushing a grocery cart full of meager supplies through a ”cauterized terrain” of charred trees and ash covered snow. The tenderness between father and son is instantly, keenly felt despite the surrounding nightmare, which gradually appears in chilling, offhand glimpses, as though McCarthy knows there is only so much we can bear to see. Houses and stores have been ransacked and left to rot; shriveled bodies lie like mummies, unburied, in bedrooms or in the middle of the road; gangs of cannibals in gas masks roam the countryside looking for fresh meat. The man and the boy face constant death from exposure, starvation, or murder. McCarthy never specifies what happened, beyond a single, flashback that suggests a nuclear disaster: Years ago, days before the boy’s birth, the clocks stopped with ”a long shear of light and then a series of low concussions.”

;

“No lists of things to be done. The day providential to itself. The hour. There is no later. This is later. All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one’s heart have a common provenance in pain. Their birth is grief and ashes. So, he whispered to the sleeping boy. I have you.”

Jared

I pleaded with God not to destroy us after reading The Road. The fire and brimstone of hell has nothing on the constant hunger and fatigue described in the book. I lay in my bed early in morning and prayed. It was a heartfelt prayer and I meant it. I’m not an alarmist, but as a kid I grew up hearing people predicting nuclear holocaust and all kinds of “in the last days” apocalyptic stuff. Nowadays, this anxiety isn’t so tied to an impending nuclear war, but hasn’t completely gone away either. We worry about global warming, asteroids, diseases, and, even more scary, we have real examples or failed nation states and atrocities in Rwanda and Cambodia, even hurricane Katrina. The one thing I take from the road is a relatable, real fear. I can see myself in that situation, and I can relate to the physiological detachment that would be necessary to survive, in this situation. Knowing that to survive your children would have to deal with constant soul-crushing realities. However, the good side to human nature is that as much as we know others are out to get us, we also know we can’t survive without each other.

I think people have noticed that the further and more advanced we are, the more dependent we become on civilization to stay alive, and the fear lies in what would happen if something pressed civilization to breaking. I think that the subconscious recognition of the fragility of civilization bubbles up in films, be it zombie movies, viruses run amuck, asteroids hitting the planet, or whatever. In the back of all our minds we fear what it would be like if… No book or film has described my underlying pathological fear about what would happen in situations like this quite as honestly as The Road. It’s not important exactly why the earth is hammered, it’s just how some people would refuse to give up and survive.

I felt compelled to read the book in two sittings. The first sitting was 10 pages, the next day I sat down and read it straight through. The landscape in the book had the feel of a western and I imagined myself trudging on a interstate. In my mind’s eye, the whole world looked like a cross between Mad Max Beyond Thunder Dome and Tooele, Utah, but hella cold. I was shocked with how much anxiety the book produced in me. I had to check on the kids and would find myself dazed. What is genius about the book is that though you get close to jumping of the cliff to end it all, you stay invested because you have genuine invested feeling about the characters in the book. You hope something will save them, though you know it’s not probable. Read The Road only if you can handle the bittersweetness of life. Read The Road only if you can bear to carry the torch.

;

I read this book in 1 sitting, early into the morning. I hate to admit this, but I took it back to the store the next day and asked for my money back. I can’t deny McCarthy’s skill as an author, but the future he laid out was so horrible that I didn’t think anyone should profit from it.

Perhaps because I was newly a father at the time I read it, I was haunted by the hopelessness of the man and his son’s journey. Preparedness whackos don’t seem so crazy to me now.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot since reading the book. On the one hand, the boy and the man are able to survive because of the preparedness whakos — they are able to scavenge from forgotten pockets of supplies here and there. But, the food storage hasn’t saved the people who stored the food. The man and the boy come upon a very old man on the road and he and the man have a brief disjointed conversation and the man asks the old man if he tried to get ready for it (disaster) and the old man says, “No. What would you do? … Even if you knew what to do you wouldnt know what to do. You wouldnt know if you wanted to do it or not.”

I haven’t read The Road, but I have read about a half-dozen of McCarthy’s other novels (Suttree, All the Pretty Horses, Outer Dark, Blood Meridian and The Orchard Keeper I think, maybe one other), and they’re all absolutely fantastic. I am admittedly leery about tackling The Road though, because I am a father of young children and I know how intense McCarthy’s writing can be, and I think I might not want to deal with being gut-punched in that particular way, if that makes sense. Other gut-punches–even severe ones–I can take, but gut-punching a father’s feelings for his young son? I’ll pass.

Kullervo, I was leery too and only tackled it after the recommendations of several good friends (also parents of young children). It is, admittedly, brutal, but it’s not only brutal, it really is beautiful. Also, the way that McCarthy writes — the short bursts of dialogue and descriptions — makes it easier to take. But, I completely understand your reservations.

(I posted this on the wrong thread, reposting it here).

The relationship between the father and son WAS the book for me (everything else faded into the background). The second time through I highlighted every exchange between the father and the son and I tried to figure out how–literally, what words were used, what punctation was used, etc.–the author had created the relationship. Some things that I thought were significant: the lack of names, the way the mother is introduced, the disagreement between the mother and the father about what would be best for the son, the way the mother’s decision to exit their lives is introduced (and how it is treated), the way the father and son interact with the outside world (their fear of it, etc.), the father’s attempt to straddle both worlds (and his realization that the boy doesn’t have the capacity to do the same), the way the father sacrifices for the boy (in a way, his life is over, and he knows it, so continuing the struggle is a sacrifice–a gift–he is giving his son), the ways the father protects the son in a physicial sense, the way the boys accepts (or doesn’t accept) the father’s sacrifice (he refused to let the father short his own rations), etc. For me, the relationship between the father and son was such a beautiful thing that under the author’s decision to put the relationship in the context of a dreary hellscape because that effectively put a spotlight on it. There isn’t anything in the book (names, other characters, plot, etc.) to detract from it. One of the first words that Heather used to describe the book after she read it (and I’m not being critical, H) was “dark”–that word didn’t even occur to me while reading it. Just the opposite.

Lame–guess I shouldn’t follow Brent’s lead.

Here’s my comment on the right post:

“And for me, the fact that McCarthy omitted names created too much distance between me and the characters. Also, the lack of context. I wanted to know their names. I wanted to know who they were, what their back story was, what had happened to get them to that point, etc., etc., etc. I know those omissions were intentional on his part, but it just left me wanting. The characters felt like cardboard cut-outs to me.

FWIW, I feel the same way when I read short stories (which is why I almost never read them anymore). I get to the end and I feel cheated. I feel like, “Wait! What about this?” and “But now what’s gonna happen??” etc. etc.”

Heather, their lack of names worked for me — they’ve been stripped down to the bone and when civilization goes, name and identity, such as you knew it before, no longer exists. Only the relationship (and the fight for survival) exists. I felt that McCarthy is giving the reader a lot of space in the story, a lot of space to come in and imagine the unimaginable. But, FWIW, I like stories that capture moments, details, how ephemeral life can be — so I like short stories and McCarthy, so — might just be down to taste. :)

Gar! Feeling like I should read it again . . .

Agreed. The bit from the text that I quoted above — “All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one’s heart have a common provenance in pain. Their birth is grief and ashes.” — gets at this idea. Joy exists because of suffering and the great suffering of the boy and the man put the “grace and beauty” of their relationship in sharp relief.

I also felt that the juxtaposition of the tenderness between the man and boy and the “hellscape” gets right at the heart of the existential dilemma of human existence. It is not enough to survive, the hollowed out cannibals, the old man — they have survived — but their humanity is no longer recognizable. It is the love between the man and the boy that preserves the fire.

I’ve only seen the movie, and I think it was enough for me. Beautiful yes, and maybe it’ll be easier when my kids are older. Right now they’re too fragile and I personalize this type of story much too much. I prefer to be just a little bit more oblivious.