Another illustration of a way to measure (in)equality in the Mormon church (for other measurements, see here, here, and here).

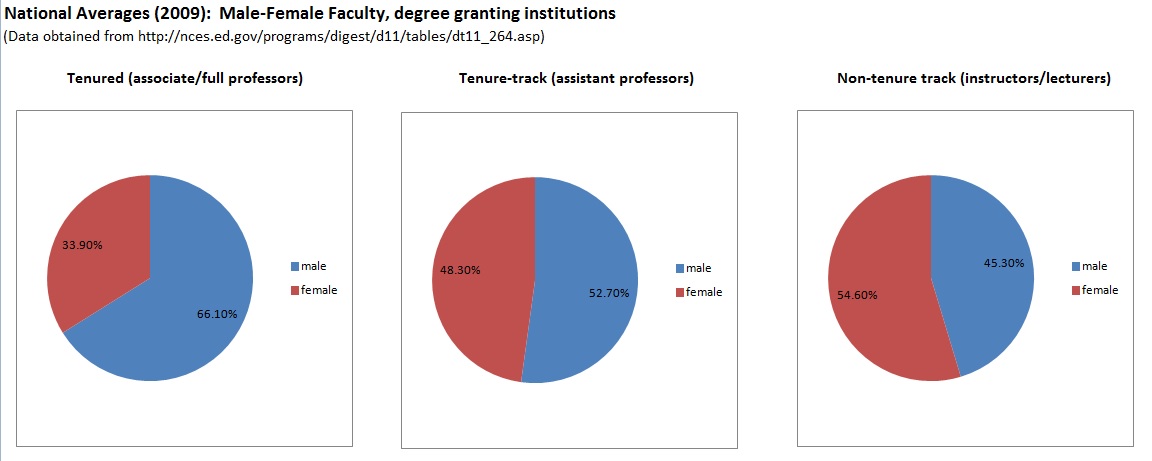

Today we’re looking at male-female faculty representation in higher education in general (degree-granting institutions, in the U.S.) versus male-female faculty representation at BYU. Now before I get too excited, I should say–right out of the gate–that higher ed is not the bastion of gender equality that it would like to claim itself to be. So the numbers in both charts are sobering, in my opinion–especially when you realize that more than 50% of college degrees are granted to female students. In 2013, 56.7% of all bachelor’s degrees, 59.9% of all master’s degrees, and 51.6% of all doctoral degrees are earned by women (click here for more info).

So something is happening between graduation and employment and between getting a job and promotion or else these numbers would look really different than they do now. Also, of course, we have to take into account that these are current figures, so we should expect to see a change in the future.

With that caveat, here’s the male-female breakdown, nationally:

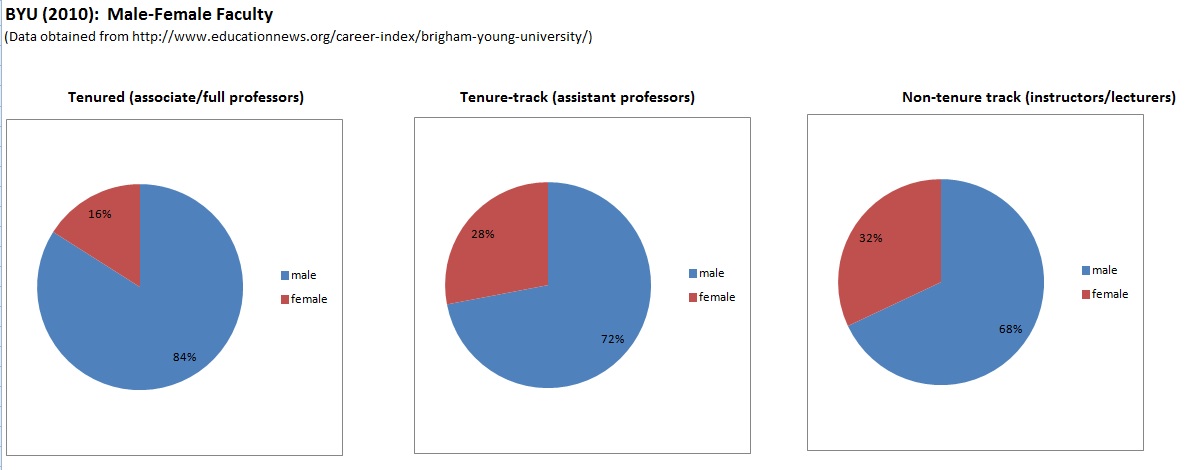

And here’s the male-female breakdown for BYU:

So BYU is about 18 percentage points behind the curve in terms of tenured professors, 20 percentage points behind in terms of tenure-track/assistant professors, and the opposite of the national average in terms of the breakdown of instructors/lecturers. I’m not sure to what to attribute that . Why are there so many more male instructors/lecturers at BYU?

Now, I know that BYU professor ranks do not equal priesthood. Of course not. But I think it’s safe ground to look at BYU–a church-funded institution run by general authorities–and say that this gender breakdown is related to church doctrine and culture with regard to men’s and women’s roles in life. I don’t think that’s a stretch at all.

As someone with a daughter about a year away from choosing a college, these numbers sure give me pause.

[For more Equality is not a Feeling posts, see the archive here.]

I didn’t go to BYU. My experiences with my stake cohort during high school, did not give me any reason to want to date LDS guys in general, and so I never seriously considered BYU. I’m the only one in my family, (siblings and step-siblings) who didn’t attend a BYU school, and all but one sister and one step-brother graduated with at least a BA degree from BYU or Ricks/BYU-I. All of my brother-in-laws are BYU graduates, as is one sister-in-law. I am the only sister or sister-in-law who has worked full-time, after having children. I see my sisters using their degrees tangentially, as an occasionally subject when blogging, tutoring, home schooling, or as foster parents. Both sisters that graduated before their husbands worked full-time through most of their first pregnancy, or adoption. From the outside, watching the choices and how they are talked about, it seems that the culture at BYU had a default to stopping work/school when a wife has the family’s first child. Choices about both working and graduate schools, seem to be more about family planning, and whether a woman is married. I know women who have chosen not to go to graduate school, worried that it would make it harder to find a husband.

I worry that with the decision in 2000, to not hire non-Mormons for tenure track positions at church schools, that the trend at BYU will get more disparate, not less. I am friends with one of the last two non-LDS women hired, before the policy was put in place. She teaches upper division and graduate economics and Business Finance, and more than half of the women professors in her area, are not LDS. As those women have retired, or taken other jobs, they are almost always replaced with male faculty members. She also has kept the data on both male and female students, who she considers excellent candidates to become tenure track professors, (meaning they have the intellectual gifts, the skills at not just comprehending, but also the ability to teach and explain concepts to others, and who are motivated students) and has been disappointed at how many of them turn down acceptance to graduate school.

When she became alarmed by how few women were choosing to continue, she started doing exit interviewing with all the students she oversees, as their advisor or professor in a 400 level class, a month before graduation. During those interviews she not only encourages them to continue, but in the cases of students who didn’t/don’t plan to apply to graduate school, or don’t accept an offered admission to a graduate program, more than 70% (sometimes higher depending on the particular school year) are women. As she has explored their choices, there are several things that are most likely to be true, of women who are choosing not to continue.

For those women who don’t apply to graduate school, most of them are married (whether they have children already doesn’t make as much difference as I would have expected) have been members of the Mormon church since birth, who had mothers who did not go to school or work after they had children, and grew up in a community where Mormons make up more than 50% of the population.

For those who applied, and were accepted, but did not choose to go to any of the graduate schools that accepted them, whether they would have to pay for going to graduate school, (so basically whether they were given a full tuition scholarship or more in financial aid) does not seem to significantly impact the choice to go to graduate school. The most common things that are true of this group are; they are married, they have children or plan to have children before they would finish graduate school, their husband is still finishing his degree at BYU or has been accepted into graduate school at a school the woman wasn’t accepted to, they were raised by a mother who did not work after having children, they were raised by a mother who did not complete a degree, and they generally do not know women who are LDS and work in the field that they would be getting their graduate degree in.

As a side note: My friend and one of the non-LDS sociology professors submitted a proposal to do a peer-reviewed, cross-discipline study of all science, math and engineering department graduates from BYU, expanding the questions and looking at post-BYU outcomes for those students as they further their academic careers post-BYU. They had the proposal denied, and both were reminded. By their chairs that as some of the only nonmember women in their departments, they needed to stop pursuing research into “faith related issues” of the BYU students.

To me this seems more like a cultural issue than a doctrinal one. I’m sure the percentages used could be equally applied to the general business population of Utah Valley. It is simply a fact that most women in Utah are not employed full-time. You can “blame” the church for this if you want, but the fact remains that the numbers shown for BYU are the norm in the surrounding community, not an abberation.

. . . which is why I said BYU faculty does not equal priesthood. But clearly, what we see at BYU is a reflection of larger church doctrine/culture . . . It’s largely subsidized by tithing dollars, after all, so I don’t think that’s too much of a stretch.

Great stuff, Heather! So I know it’s easy for me to just throw this out without considering how much work it might be, but have you considered looking at BYU-Idaho? I wonder if the faculty there isn’t even more dominated by men.

Aren’t there more data to tease out about the whys and wherefores of this gender imbalance? How many qualified candidates of each gender are there? If they have to be LDS (I never went to BYU — I went to the “other” school), then the pool of female candidates may shrink. As Nameless points out, daughters of women who didn’t go to school may not pursue further education, but the same can be said of the males. In a local tribe I’ve worked with, where few of the parents went past 7th grade, it is simply difficult to get the kids to think about going past their parents. Utah and the Intermountain West have largely rural components, but I’m only be guessing at what the true demographics of the BYU student body are, since I’m less familiar with that area and school. Not to recently, an engineering department had to battle the administration at a UC campus because the administration and higher-ups insisted on a sub-par female candidate to the exclusion of better-qualified male candidates simply for gender-balance. This effort only cheats students, and who would want a sub-par education for their child, especially at UC tuition rates? Fortunately for the school, the engineering faculty prevailed, but it was close. I don’t care so much about the gender of an instructor or professor, as long as they’re qualified and reasonably human (negative examples of behavior at the tenure-track level are unacceptable to me).

Many brilliant, well-schooled and accomplished women choose to become full-time moms. There is no dishonor in this, as raising the next generation is really, really important, and it’s an individual choice. If the Lord is mindful of all his children, and his children remember him, their talents won’t be wasted.

What’s curious is why a cocked gender imbalance is something you see would be a reason for your daughter to not go to BYU, or any particular school. The important thing about school for an LDS kid is two-fold — get the education (and possible training), and hang onto and develop a testimony as they mature into an adult. The quality of the school one’s child attends is important, as cost is, too, and BYU has improved quite a bit over the years. I used to think about BYU rather negatively until I spent some time on campus for another reason in my college days, and then I realized it was no crazier than so many other campuses across the country, and has fewer alcohol-related problems (and had a pretty good art program). Prayerful consideration would seem to be more important than arbitrary PC criteria, wouldn’t it? The idiocy that passes for enlightenment on many campuses these days is wearying, and the lucky/wise students ignore the PC trash and concentrate on their studies, unless the instructor or professor is so hide-bound in his or her ideology that common sense had departed them some time previously.

Observer, I don’t consider gender equality an example of “PC trash.”

Why couldn’t including information about the school–like how likely a woman is to find female role models among the faculty there–in one’s prayerful consideration? I don’t think the point is to be blind and expect God to strike you with a bolt of lightning. And having role models you can identify with *is* important, if you want your kids to take school seriously, graduate, etc. It’s not, as Heather points out, “PC trash.”

I’ve reread my post and am hard-pressed to find where I had said that, Heather. Regarding PC trash — I was speaking generally, not specifically, so I’m sorry if you thought otherwise. Ziff, neither did I say to be blind in the direction. While if that (role-model availability) is important to a student, he/she can consider it, but isn’t it more important to follow and learn from the Lord’s counsel in directions for folks to influence them? The Lord seems to post individuals in our lives regardless of our location and direction, if we have eyes to see and ears to hear, as a formative time for young adults, learning to live and internalize the Gospel on one’s own is important. Answers to prayers, understanding and becoming acquainted with the Spirit as well as everything else.

As far as role models and school, I spent some time reflecting on role models and who of all my mine were (I had a lot of time while I was driving). Role models are where you find them (a terse summation of all I’ve heard on them, and in my experience), and most of the ones I found were in the work environment. Whether that’s a reflection on academia or not, I don’t know. Memorable faculty at school were few, surprisingly, in my review — I’d never considered it before, so thanks for the motivation to review that time in my life. There was a chemistry professor I never had a class from, but whom I’d met and he was a remarkable find: gracious, humble, kind, and brilliant and of international renown, I saw in him how the human factor should never be forgotten. Other individuals in my student ward and stake leadership — there were kids of the apostles there (both genders), though I hadn’t recognized it at the time, and they reflected well on their own independence, and their parents. Academia is a tough environment, where talented and accomplished individuals compete for limited resources, and the political atmosphere fraught with battles of words. Expecting to find role models there seems curious isolated goal. Hopefully a child’s parents and others in his or her earlier life will have already been posted as models. At a funeral for a cousin’s mom I’ve just returned from, she was never “more” than the receptionist at the local institute of religion, but at her death, her kids were inundated with letters and phone calls from students whose lives she’d touched. She was a remarkable role model: kind, intelligent, uplifting and encouraging. Role models are where you find them, and character counts.

If you think that “role model” only means “people who show me how to be a decent human being” then yes, your comments make sense. But a female student aspiring to academia can’t ask a receptionist how she managed to make international research opportunities work within her marriage. She can’t ask a male professor how he managed to navigate pregnancy while in grad school or on tenure track research. She can’t ask a male professor about how he endured when he was the odd woman out in an all-boys club. She can’t ask a male professor how he overcame institutionalized sexism (which is shown to exist in very recent studies) to get to where he is today. And so on. Female students need a female role model to look to for these kinds of concerns; receptionists and male professors simply do not fit the bill.

Pleiades, they don’t need a role-model so much as someone who knows how to tread through those mazes you’ve described. A role model would be great, but someone who knows the ropes, too. You might be underestimating the power of kind receptionists (who might have important connections to get things done) and male professors (who have wives who know more about those particular challenges, and who may have daughters they value). The down side of academia is the sort of institutionalized bitterness among so many, and it takes a remarkable person to work past those and be a good academician, and remain a human with a heart. The embittered academicians, female as well as male, will they pass on their bitterness, or encourage the development of it?

I’m really late to this party but feel compelled to respond.

First (as you’ve said) correlation and causation are different. I 100% think this is a Mormon culture thing and not a BYU thing.

I have several female LDS acquaintances with PhDs and BYU has kept very close tabs on all of them. BYU recognizes females are underrepresented in faculty positions and has courted these women with PhDs, although none have gone to teach at BYU at this time.

I believe it would be useful to combat the Mormon cultural bias against mothers working outside the home, and that would hopefully improve this statistic.

For this post to be more valuable, I’d propose research into the following.

– Data on the percentage of LDS women compared to the percentage of LDS men receiving PhDs, which is arguably a valuable qualifier for teaching and a good measure of whether the faculty is representative of the pool of qualified applicants.

– Current hiring practices, to see if current practices are in line with national averages.

– Gender breakdown compared to years worked at BYU. This would show how things have been progressing, and if there is an “Old Guard” of men with tenure from a time period when LDS women were less inclined to be a part of the workforce.

– Percentage of LDS women working outside the home compared to national averages. If the ratio of professors to general workers is same for both LDS women and national women, I’d would again point to the bias of women not working.

All-in-all, I think this is a very interesting post which, to me, illustrates the need to combat the bias against women working outside the home.