Today’s guest post comes to us from Brad Jones.

Heather’s post the other day on the allocation of time between men and women is a stark portrayal of one form of gender inequality in the Church. Without question, women speak less frequently then men in General Conference. Given the status quo (an all-male priesthood), it is difficult for me to imagine a world where women and men have equal time at the general conference pulpit, but it is at least possible that the gender inequality isn’t as bad as it first appears.

One of the reasons for worrying about the gender imbalance in the speakers in conference is because we are worried that men cannot adequately address the concerns of women. (Greatly simplifying a complex issue) in democratic theory, scholars who think about representation distinguish between descriptive representation (does the person who represents me in politics look like me in terms of gender, race, sexual orientation, religion, or some other demographic characteristic that is important to me) and substantive representation (does the person who represents me in politics look after my interests regardless of the congruence between our identities). One of the big questions for political scientists and others is determining what consequences descriptive representation (or a lack of it) has on substantive representation. [1]

For a lot of reasons, the analogy between representative political institutions and religious institutions is strained, but I think it is worth at least considering the idea that even pre-dominantly male speakers could represent the substantive interests of women (and other groups) in their General Conference addresses while they provide an exceedingly poor reflection of their audience. Surely a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for this kind of substantive representation is references to the stories and experiences of women in their talks.

The data

I downloaded all of the General Conference addresses available from www.lds.org (extending back to 1971). For more on the data, you can see this post. [2]

As a (very) rough measure of the references to men and women in their talks, I searched the text of each talk for words associated with men and women (“he”, “she”, “man”, “woman”, “boy”, “girl”, etc.). I then summed up all references to women and divided them by the sum of all references to women. We would expect to see this figure hovering around one if there were perfect equality in the references between men and women. A zero would mean no references to women, and a number greater than one would mean more references to women than men.

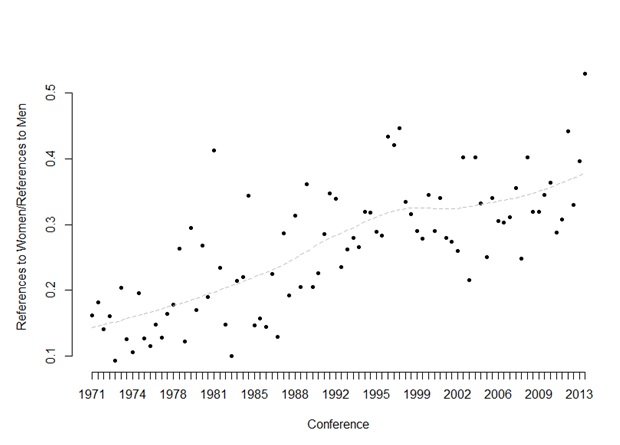

The plot below shows the ratio of female-to-male references over the last four decades of General Conferences.

The plot above shows the results by conference. The x-axis plots the date of the conference, and the y-axis shows the ratio of references to women and men. In the early 1970s there were more than 10 references to men for every reference to a woman. In recent years this ratio has become much more equal. The latest conference is the most equal conference for those that I have data, but there are still two references to men for every reference to a woman.

What I’ve presented so far is a very crude measure indeed. It tells us nothing about how general conference speakers talk about men and women, but it does seem to suggest that they are talking about women relatively more frequently in recent years.

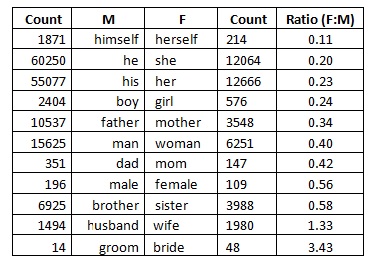

One (still crude) way to get at the sticky question of “how?” is to examine which gendered words are most often used. The table below reports the overall counts and ratios for the root forms of the gendered words I used in my search. For example, the first row shows the word “himself” compared to usage of the word “herself.” This word shows the most inequity with a male to female ratio of nearly nine. For every one use of “herself,” “himself” is used 8.7 times.

Interestingly the only female words that are used more frequently than their corresponding male words are “wife” and “bride.”

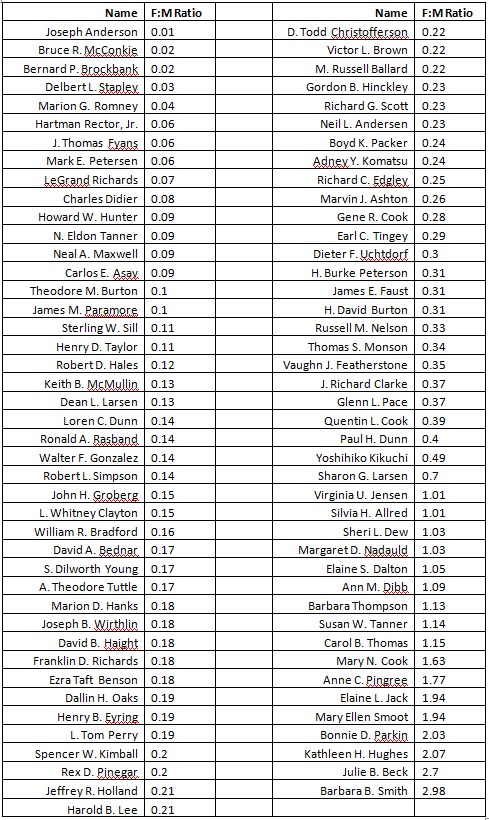

Finally, we can look at the ratio of female to male words for individual speakers. For each speaker who has given at least 10 talks in general conference, I calculated a ratio of the number of female to male words. The table shows the scores (values closer to 1 are roughly equal, less than 1 means relatively more male words, greater than 1 means relatively more female words).

The gap between male and female speakers is quite striking.

This is Heather speaking now, although I certainly did not collect or organize all this data:

So, Doves and Serpents readers, what do you make of all this data? Do the data suggest positive trends towards more inclusion of more female-centric content or more efforts to include the experiences of women in General Conference content? What do the data say about substantive versus descriptive representation? Which is more important in a religious institution: substantive or descriptive representation? In my opinion, Mormon women are lacking in both types.

To what might we attribute these trends?

Not surprisingly, I have some ideas about all of the above, but I’ll let you sift through the data and offer up your suggestions.

[1] If you are interested in this sort of thing, David Canon’s Race, Redistricting, and Representation makes a compelling argument that descriptive representation leads to substantive representation by looking at “majority-minority” districts in the United States.

[2] One point does bear some discussion here. In recent years, the Conference issue of the Ensign has printed the report of the General Young Women’s meeting in the May issue and the General Relief Society meeting in the November issue. This has not always been the case. I’m moving forward with this analysis under the assumption that what is printed in the conference edition of the Ensign is a reflection of what the Church would like to publicize about General Conference. A part of the trend we will see relates to the inclusion of these sessions directed at women. Unfortunately, it isn’t straightforward to tag the texts with the session of Conference it was delivered in. Ideally, we could control in some measure for the intended audience of the speaker.

The use of the words “wife” and “bride” being used more often seems to me to reflect a view that women are most consequential in their relationship to men….. I’m sure things are getting better, but we really do have a long way to go, don’t we? :(

ldslara — I had the same thought when I saw the results.

ldslara, Brad,

As men are most consequential in their relationship to women. We can’t forget that it’s only married men that are priesthood leaders (bishops and on), and that a certain unity is expected (ref. Pres. Eyring’s Sun a.m. talk in the Oct 2013 conference).

While the data is very interesting, and denotes a rather male-centric focus (which is hardly surprising to anyone who grew up in the church) it doesn’t reflect the context of when the words are used. The indication from the use of wife/bride as dominant over husband/groom reflects that idea, but it also reflects ideas about common english usage.

(They are most often announced as man and wife- not husband and wife. This not only indicates that women lose all status of their own and are now an addendum to him, fitting the historical understanding of marriage, but also that an unmarried man is not a man at all, but a boy.)

It would be interesting to do a data search on which words are used to describe certain genders, and what the general message is. There are instances such as the talk that President Monson gave on charity in RS conference last year (or two years ago?). I loved the message of that talk, and it was at a woman’s conference, so it is fitting that the characters in the stories were women. But in the story of “judging through your own dirty windows”, it was the woman who was busy judging the other woman, and the put upon husband that had to listen to it and then point out the error. I think this fits into a meme about women and feeds the stereotypes about women and their ability to show good judgement. I know it is nit picking, and not necessarily the intent of the talk, but it does feed into that preconception that people use as an argument against women’s leadership, a preconception that I think is demonstrably false. It seems folksy and charming, and I don’t believe there was any ill intent involved. It just seems like an instance of the culture reinforcing its stereotypes. Those subtle references can be the most damaging and it would be interesting to see if there is a way to visually represent that. maybe a pie chart…

Rachel – thanks for your feedback. I’m thinking through ways to systematically get at the context. I absolutely agree that the bare-bones count up the words approach is less than ideal. Your idea about looking into how men and women are described is really interesting. I’ll have to think about how to do it. Thanks again!

“I then summed up all references to women and divided them by the sum of all references to women.” I think one of the uses of “women” here must have been meant to be “men.” Which one?

Thanks

You are right, Jeanmarie. I should have said “I then summed up all references to women and divided them by the sum of all references to men”

Very interesting! I’m just curious – did you include the Priesthood and Relief Society Sessions in the analysis?

Yes… when available. RS sessions haven’t always been printed in the Conference edition of the Ensign (see the 2nd footnote).

One thing that’s missing in this is usage analysis is accounting for how English is used and has been used, and the changes in usage over the years. Because English, even though its nouns generally lack gender, lacks a non-specific pronoun for an individual, so linguistically, the third-person singular pronoun “he”, in traditional English, can either mean a male or a person of either gender, and the meaning is generally derived from context. Similarly, the word “man” could mean a man, or an adult human of either gender, or the human race itself. Starting in the 70s (or so) attention was paid to this, and some language forms and usage shifted, but back then (and considering that speakers were raised during the time of “traditional” usage of these words), this traditional form was simple considered good English usage. So, counting “he” or “him” and “man” will show a skew of “gender bias” in a modern view, but back then, it was simply following good English usage. Accounting for this usage will require more work than a simple count of specific words, but an examination of context. I’m not sure if it would change things much in the tables, but I think this needs to be pointed out, since that older English usage is less likely to be considered these days. Other languages have different problems — for instance, in French where all nouns have gender, the word for “person” is a feminine noun, but the person it refers to could be a person of either gender.

Ah, but in the past 20 years, most public speakers have found ways to include women in references through various means: swapping male/female pronouns; creating plural rather than singular references; and, when reading quotes, include “(or she/her)”

Even editors at the Ensign do this when they use old conference talks to create new First Presidency messages. Look at what ET Benson or GB Hinckley said in the early 1970s and then read the re-edited versions that showed up in their messages 20-30 years later.

It would be interesting to see how many of the times someone used “mother” or “wife” were times when the speakers were merely referencing their own “angel mothers” or “wonderful supportive wives” in passing (rather than addressing something specifically about women).

It would also be interesting to figure out which of those feminine pronouns were in reference to Zion or Wisdom (which are usually feminine).

And, finally, I’d like to see how many of the male references are scripture quotations and/or references to godhead members.

LRC, I understand that completely. Since the table includes items dating back to 1971 (where the first Ensign is carried on the church’s Web site), that usage would include the older forms as well. I would hazard a guess that when “universal” principles are discussed by general authorities, that’s where the he/him/his/man would have the inclusive (both gender) meaning. Your point about Zion and Wisdom is apropos.

Great suggestions, LRC! I’ll have to look more into that.

Observer — I did do a little check of this, and you can see a similar trend in the Google Books corpus (https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=he%2Cshe&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Che%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cshe%3B%2Cc0).

You are right to note that there is a general trend in the wider (American) culture that might just be being reflected in conference talks.