Sparring with Dictée

Over a decade ago, when I was a young whippersnapper of 21, I left my home and family to be a missionary for the LDS church. The place I was assigned to by the Church Presidency was the Canada Montreal Mission, which encompasses all of Quebec and half of Ontario. The language I was assigned was French. Although I’d had a smattering of French classes in high school and college, I was nowhere near speaking proficiency. Not even close.

I arrived in Trois Rivières on January 1st, 2002, on a bitterly cold winter day. I remember getting out of a car with my missionary companion, Sister Iwasa, for a few hours of porte-à -porte. The sun was shining on the bright snow, and in the back of someone’s yard was a statue of the Virgin Mary blanketed in white. My heart pounded as we approached my first door. I’d been taught what to say. I’d memorized chunks of French I could use like tools from a toolkit. My companion knocked. She began to introduce us in French, and within a couple seconds the man at the door released a torrent, floodtide of unintelligible garble, before slamming the door.

We went to the next door. Sister Iwasa instructed that it was my turn. I knocked, my tongue dry as an old wasp nest. The door opened. A man with a large belly looked us over. I began telling him who we were: “Bonjour. Je m’appelle Soeur Kidd et voici mon ami Soeur Iwasa. Nous sommes missionaires de l’Eglise-” Before I could finish, he unleashed a barrage of syllables and consonants, only one word of which I thought I grasped: peau, (pronounced POE, as in Edgar Allen), which means skin. That seemed wildly inappropriate.

As we walked away, I asked my comp why he would bring up skin. She shook her head and laughed. “He was saying ‘pas,’ as in,” here she slowed down and enunciated like you would for a preschooler: “Ça ne m’interesse pas.” That doesn’t interest me.

Unlike English, French requires a double negative, the “ne” and “pas” surrounds the verb like a fence, a wall. In this case, it enclosed the verb “interesser,” to be interested. The gentleman who’d turned us away had put extra emphasis on his “pas,” an exclamation point for his rejection of us, our message.

After that, I heard the phrase repeated many thousands of times, and each “pas” was a little punch to my gut. I was in a very different place spiritually than I am in now, but I still remember the pain of rejection, the giant hurdle of speech in another language, the burning to be heard.

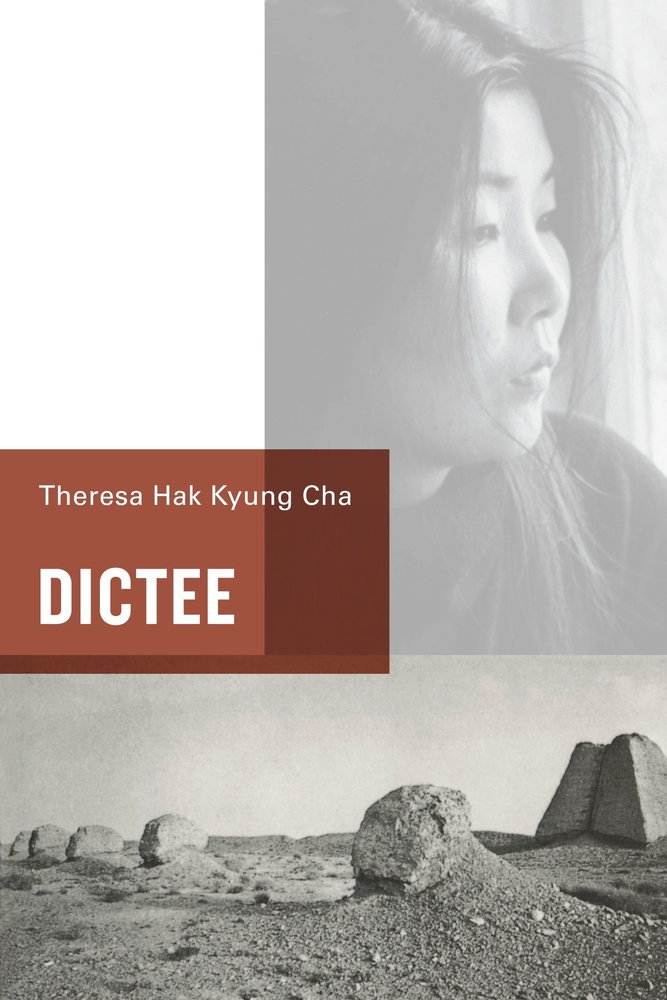

These memories swirled around in my head as I read Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée for the first time. Her book is difficult and dense. At first I thought I could relate to the (anti)diseuse, the “she” described in the process of trying to speak: “She mimicks the speaking. That might resemble speech. (Anything at all.) Bared noise, groan, bits torn from words. Since she hesitates to measure the accuracy, she resorts to mimicking gestures with the mouth” (3). Since I didn’t speak French well when I arrived in Quebec, I resorted to memorization, mimicking the best I could the foreign sounds that surrounded me. I felt I could commiserate with Cha’s words, “It murmurs inside. It murmurs. Inside is the pain of speech the pain to say” (3).

These memories swirled around in my head as I read Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée for the first time. Her book is difficult and dense. At first I thought I could relate to the (anti)diseuse, the “she” described in the process of trying to speak: “She mimicks the speaking. That might resemble speech. (Anything at all.) Bared noise, groan, bits torn from words. Since she hesitates to measure the accuracy, she resorts to mimicking gestures with the mouth” (3). Since I didn’t speak French well when I arrived in Quebec, I resorted to memorization, mimicking the best I could the foreign sounds that surrounded me. I felt I could commiserate with Cha’s words, “It murmurs inside. It murmurs. Inside is the pain of speech the pain to say” (3).

As I got further along in the book, however, Cha’s text began to feel more and more like the man at the door, pushing me away, rejecting me. And I recognized that in vital ways my experience was nothing like what I was reading. Cha doesn’t just describe the difficulty of speaking another language, but the pain of colonization, of having one’s homeland ripped away, of being forced to speak a language against one’s will, of having one’s native language barred. I was in Canada by choice (although I gladly would’ve returned home after my first day of going door to door, if it weren’t for the cultural shame and stigma I would’ve had to endure). I was excited about learning French better, a language I’d always thought of as sonorous and beautiful. If anything, I was more like a colonizer, working to assimilate others into the religion I felt was True (as in Plato’s True).

Ironically, Cha incorporates a lot of French into her text, which for me was a way in, although I don’t think it is meant to be a way in for most readers. I think Cha meant for the large chunks of French to further alienate her readers, perhaps forcing them to feel on some level how a colonial subject or refugee might feel. Even when she translates, her translations reveal the impossibility of translation and how languages do different things. In the Urania/Astronomy section, for example, cygnes/signes are homophonous in French, but in English they are not: swans/signs (70). The difference allows the French poem to play with language in a way that the English version cannot. Conversely, Cha plays with the English version in ways that wouldn’t work in French. She creates enjambment from the verb “Dim / inish” and separates “Re membered,” drawing attention to the meanings embedded in the words themselves (69).

But there is no getting around it. Cha’s is an unwelcoming text. It shoves back, sometimes with short, chopped up sentences, and other times with opaque references and images. It shuts the door and clearly says, “PAS.” Cha’s book is one that I will return to, for the French, for the elegant structure, for its mystery. But not for awhile. Not till I’m in ready to be punching bag.