On almost every page, this book is a gut punch. It is the haunting song of an Arab American in the wake of 9/11 and the “War on Terror.” It exposes the reader to a few of the harrowing details of the Abu Ghraib torture scandal. It tours the darkest, most abhorrent circles of hell, yet manages to allow for a doorwedge of light.

On almost every page, this book is a gut punch. It is the haunting song of an Arab American in the wake of 9/11 and the “War on Terror.” It exposes the reader to a few of the harrowing details of the Abu Ghraib torture scandal. It tours the darkest, most abhorrent circles of hell, yet manages to allow for a doorwedge of light.

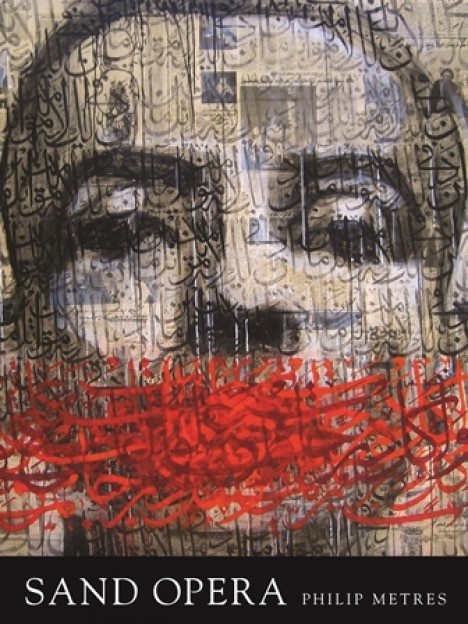

Sand Opera was released in 2015 by Alice James Books. Poet Philip Metres has written several books and chapbooks, including A Concordance of Leaves (Diode 2013), abu ghraib arias (Flying Guillotine, 2011), and To See the Earth (Cleveland State, 2008).

Metres organized Sand Opera using the structure of an opera as a loose frame. After an introductory poem about the flaying of St Bartholomew (the overture), which sets the tone for the poems to come, there are five sections: I. abu ghraib arias, II. first recitative, III. hung lyres, IV. second recitative, and V. homefront/removes. The book closes with a prayer poem, a delicately balanced finale piece that resonates long after the curtains close.

While an operatic aria is usually a melodic solo piece, Metres’s arias move between dialogic weavings of torture victims, to persona poems from the perspective of the soldiers at Abu Ghraib. Metres draws upon a number of sources in the first section, including the testimonies of torture victims, making this section one of the most emotionally difficult to read.

The recitative sections include poems from a variety of perspectives-a drone operator who goes home to his kids at night; an Iraqi curator delivering a powerpoint about art that has gone missing or has been vandalized; a widow who crawls into the tank in which her partner drowned to see the scratch marks he left. These poetic voices add to the opera’s multivocal quality.

The impact of Metres’s work is memorable not just because of the poems’ content, but what Metres leaves out. He works variously with erasure and redactive blackout. (The book’s title is a blacked out form of “Standard Operating Procedure.”) A few pages are printed on opaque vellum and overlay text and image. Sometimes this erasure looks like a lot of white space on the page. Sometimes it takes the form of gray versus black text. And sometimes it looks as if someone has taken a chisel-tip black marker to the page as a form of censorship, except here Metres is the one censoring. The text speaks fathoms deep through the poet’s selective omissions. We are left as readers wondering what a particular torture victim saw, what horrendous, unnameable thing. The imagination is free to paint monstrosity.

One aspect of this collection that is particularly resonant for me is Metres’s own wrestling with the how of raising children in a violent world. He writes in his endnotes: “I continue to ask myself what it means to be a human being-and what it means to rear vulnerable creatures-in a world where humans seem hell-bent on violence, using ‘defence’ and ‘security’ as alibis for domination and revenge” (101).

As the mother of two vulnerable creatures, I have struggled to answer their questions on more than one occasion. What is a Nazi? Why do we have Martin Luther King, Jr. Day? Why would someone crash a plane into a building? Metres folds some of his own daughters’ questions into his poems: “what does it mean, amputee?” and “is there such a thing as ‘orphan’?” (54). He dwells on the image of the ear in a series of poems entitled “@,” exploring how children pick up heavy words before they are able to lift. “Cover your ears,” the speaker says, “your cartilage is not yet hard-/ it’s too soon to know to hear is to bend” (54). I, too, have felt the impulse to shelter, to cover ears, to shield my children from a mutilated world.

Metres’s poems that sound his concern over the vulnerability of his children help to leaven a dark load. The last poem of the collection, “Compline,” also invites a measure of hope. A compline is a kind of prayer usually said before going to bed, and the poem lends a kind of nighttime closure. Metres combines war and parenting imagery side by side, ending with an invocation: “We lift the blinds, look out into ink / For light. My God, my God, open the spine binding our sight” (97). Whether or not you’re a believer, after reading these poems, you’ll be praying these words in your own way.