The epigraph to Monica Ong’s book, Silent Anatomies, reads:

The epigraph to Monica Ong’s book, Silent Anatomies, reads:

“I wish I could tenderly lift from the dark side of history, voices that are anonymous, slighted-inarticulate” (Susan Howe).

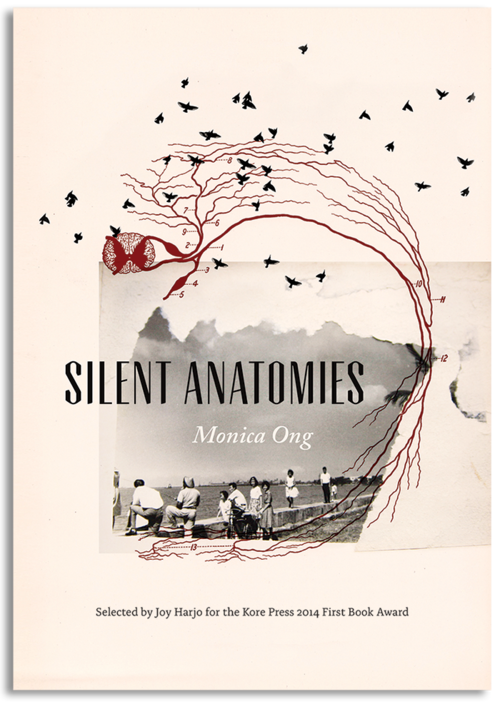

And this is exactly what Ong accomplishes: her work gives voice to a slighted, less often heard side of history. Ong creates a speaker in the book who traces her ancestry from China to the Philippines to the United States, complicating the narrative of Chinese diasporic experience. It echoes, in many ways, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, but it is a far more inviting read. There are endnotes that give additional details both about the text and the illustrations, which help to open up these poetic compositions for the reader.

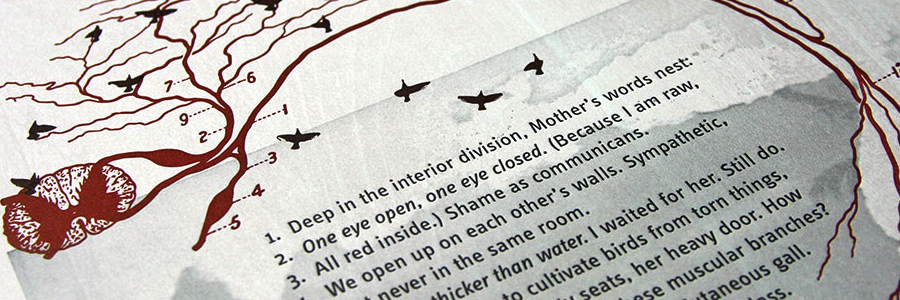

Ong’s book was selected by Kore Press for their 2014 First Book Award. Joy Harjo, the judge, calls the book “highly experimental and exciting.” And it’s no wonder why. Monica Ong is not only a poet, but a visual artist. She received her MFA in Digital Media at the Rhode Island School of Design, and her expertise is apparent in this collection. The speaker tells the stories of her ancestors through poems accompanied by photographs, recipes, brain scans, bone x-rays, and beautifully manipulated anatomical sketches. The speaker also connects to future generations by including sonograms overlaid with poetic text and image.

One example of Ong bringing together both visual art and poetry is her series of medicine bottles, many of which are included in this collection. The medicine bottles include satirically biting labels as “Yeong Mae’s Whitening Solution,” which promises to lighten skin and “Yeong Mae’s Oral Whitening rinse,” with an equally absurd guarantee to help you “lose your accent in 30 days” (21). The bottles are physical objects, vintage glass bottles Ong acquired and made new labels for. Some of the bottles are filled with round, white pills. Others appear to be full of liquid. The bottles began as an art installation, and were photographed for this collection. Ong’s work with these medicine bottles is more than a poem on a page. They marry the visual and poetic to form an embodied composition with a life beyond the page.

Ong uses these compositions as vehicles for feminist critique. It is one of the threads that run throughout the collection. In the second poem and image composition, entitled “Bo Suerte,” there is a digitally-manipulated photograph of a young woman and seven children, four girls and three boys. We learn from the poem that the young woman is the nanny, and that one of the boys is actually a girl, the speaker’s mother. To find out why the parents would dress her as a boy, the reader must sift through the clues in the poem:

He didn’t want people shaking their heads, their tongues clicking

. . .

This terror of asymmetry. This shortage of sons. (3)

In another composition, a medicine bottle called “Fortune Babies,” the directions read: “If you have difficulty conceiving, adopt a little boy so / that spirits fill your home with blessings for many sons” (7). Yet another medicine bottle shows a picture of a baby boy in a shirt but no breeches. In the endnotes, Ong writes that this is a found image of newborn sent to her grandparents, a kind of baby announcement as undisputable photographic evidence of maleness. The medicine/poem is called “Perfect Baby Formula” to be used for fetal “gender correction treatment” (15).

In a later poem, ” Etymology of an Untranslated Cervix,” we learn that there is no word for cervix in some languages. The speaker struggles to explain to someone she cares for that this person has cervical cancer, but since there is no word for cervix, the danger feels more monstrous, “taller and hungrier than the monster itself” (40). Language fails both the speaker and the spoken to, creating an absence that is “unable to make real / her body, written in silence” (40). The image Ong pairs with the poem is a pelvic bone scan overlaid with a photograph of tall, dark fir trees and the silhouette of small helicopter above them. The white flaring of bone above trees look like flames, and echo the poem’s line “What is the point of wailing horns, of fighting / a fire with no address?” (40). Ong’s compositions underscore the reality that misogyny runs deep-from cultural shaming over daughter to son ratios, to fatal absences in language.

In a later poem, ” Etymology of an Untranslated Cervix,” we learn that there is no word for cervix in some languages. The speaker struggles to explain to someone she cares for that this person has cervical cancer, but since there is no word for cervix, the danger feels more monstrous, “taller and hungrier than the monster itself” (40). Language fails both the speaker and the spoken to, creating an absence that is “unable to make real / her body, written in silence” (40). The image Ong pairs with the poem is a pelvic bone scan overlaid with a photograph of tall, dark fir trees and the silhouette of small helicopter above them. The white flaring of bone above trees look like flames, and echo the poem’s line “What is the point of wailing horns, of fighting / a fire with no address?” (40). Ong’s compositions underscore the reality that misogyny runs deep-from cultural shaming over daughter to son ratios, to fatal absences in language.

I echo Harjo in saying that Ong’s work is highly experimental and exciting. She elevates poetry to a new level, creating compositions that open up the genre and respond to the visual expediency of a digital era.