You’ve probably had the pleasure of being sucked into a really beautiful magazine, a National Geographic, for example, or The Smithsonian. You may have felt the inertia of a story winding down as you simultaneously tire of the style of storytelling and pictures. You come to the end of that column, only to turn the page and begin to immerse yourself in something refreshingly different. Matthea Harvey‘s new book, If the Tabloids Are True What Are You? reads like that, like a beautiful magazine with somewhat disparate pieces stitched together.

You’ve probably had the pleasure of being sucked into a really beautiful magazine, a National Geographic, for example, or The Smithsonian. You may have felt the inertia of a story winding down as you simultaneously tire of the style of storytelling and pictures. You come to the end of that column, only to turn the page and begin to immerse yourself in something refreshingly different. Matthea Harvey‘s new book, If the Tabloids Are True What Are You? reads like that, like a beautiful magazine with somewhat disparate pieces stitched together.

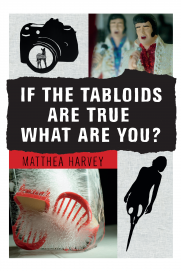

Tabloids was released in 2014 by Graywolf Press, and because there are so many stunning color prints, it’s a little pricier than your average book of poems. (I purchased my copy at a local bookstore for $25.00.) If you struggle with reading a straight up book of poetry sans visuals, or if your attention span can get you through a chapbook but not normally a full-length collection, I recommend Harvey’s book.

Harvey is not only a poet, but a graphic artist. The book includes an impressive range of multimedia art: cross-stitched images, tiny figurines in ice cubes, bobbles of colorful glass, pictures of waxy-looking TVs with pictures on them. I don’t have the words to describe all of what she does in this book-I’m not a graphic artist-but each piece offers intrigue, and pairs well, most of the time, with its accompanying text.

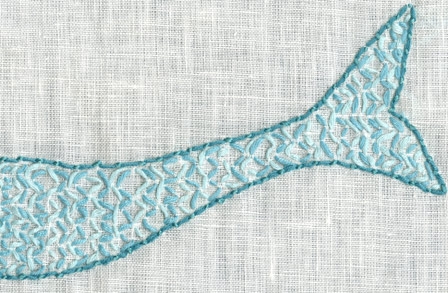

The book opens with black cutouts of mermaids, shadow images, but there is something unusual about them. The top halves look normal enough, but the women’s torsos are spliced with unusual fins: scissors, a saw, a Swiss army knife, a revolver.

The poems that accompany the images are also unique: “The Straightforward Mermaid” who “starts all her sentences with ‘Look . . .'” (3). “The Tired Mermaid” who takes a bite of an electric eel for a jolt of caffeine (11). “The Backyard Mermaid” who wriggles “under fence after fence to reach the house four down which has an aquarium in the back window” (15).

The poems, just like the images, are blends; mer-lore meets struggling, modern-day woman. And just when you might start to grow tired of the subtle feminist critique lurking like an underwater creature in these poems, Harvey shifts to something completely different, a erasure of Ray Bradbury’s “R is for Rocket.”

My favorite part of the book, entitled “Telettrofono,” comes at the very end. It’s a series of delicate cross-stitched pieces and loosely narrative poems about the original inventor of the telephone, Antonio Meucci, and his costume-designer wife, Esterre. I’d never heard of Meucci, only the famous Alexander Graham Bell; these poems elucidate why. Harvey takes creative license, transforming Esterre into a mermaid in love with sound, so in love that she leaves the silent sea. She becomes Meucci’s muse for whom he continually churns out invention after invention, including a loudly-fizzing (not loud enough for Esterre) soft drink dispenser. The series is part fairytale love story, part heartbreaking history of unrecognized genius.

My favorite part of the book, entitled “Telettrofono,” comes at the very end. It’s a series of delicate cross-stitched pieces and loosely narrative poems about the original inventor of the telephone, Antonio Meucci, and his costume-designer wife, Esterre. I’d never heard of Meucci, only the famous Alexander Graham Bell; these poems elucidate why. Harvey takes creative license, transforming Esterre into a mermaid in love with sound, so in love that she leaves the silent sea. She becomes Meucci’s muse for whom he continually churns out invention after invention, including a loudly-fizzing (not loud enough for Esterre) soft drink dispenser. The series is part fairytale love story, part heartbreaking history of unrecognized genius.

The danger of Harvey’s recent book is that it can feel disjointed, like a summation of individual chapbooks or projects that have been lumped into a monograph. And that is precisely what it is. Glancing over the “Acknowledgements” and “Collaborations” pages reveals this. The fact that the mermaid theme from the beginning reappears at the end lends the collection as a whole a kind of circularity, illusory though it may be. However, as the title of the work suggests, the book is meant to be tabloid-like, a conglomeration of unusual creatures, disharmonious under one ocean.