I have a new hobby: reading while I walk on the treadmill. A certain amount of attentiveness is required so I don’t fall off, but happily I have no accidents-as yet-to report.

I have a new hobby: reading while I walk on the treadmill. A certain amount of attentiveness is required so I don’t fall off, but happily I have no accidents-as yet-to report.

If you have a treadmill, and like to read, I highly recommend it. Lost in a book, the minutes will race by. It’s like entering a time warp. Before you know it you’ve walked several miles, all while nourishing your mind with the reading material you’ve selected.

And because you’re exercising while reading, blood is pumping to your brain, allowing you to absorb what you read more thoroughly. The exercise and the reading complement each other neatly.

I have only one fail to report since I picked up this hobby, and it’s name is LoterÃa Cards and Fortune Poems. I hopped on the treadmill last week, the pleasing weight of this small hardback in my hands, looking forward to an hour of walking and intellectual stimulation. Commence time warp!

Alas, it was not to be. Every couple of minutes, I found myself checking and rechecking the big red numbers on the digital timer just above the book’s horizon. Geez! It’s only been ten minutes!? How is this happening?

I will tell you. While the book contains splendidly intricate and intriguing linocuts on every other page, the poems are more or less forgettable. Artemio Rodriguez made the linocuts first, and then Juan Felipe Herrera wrote poems to accompany each image.

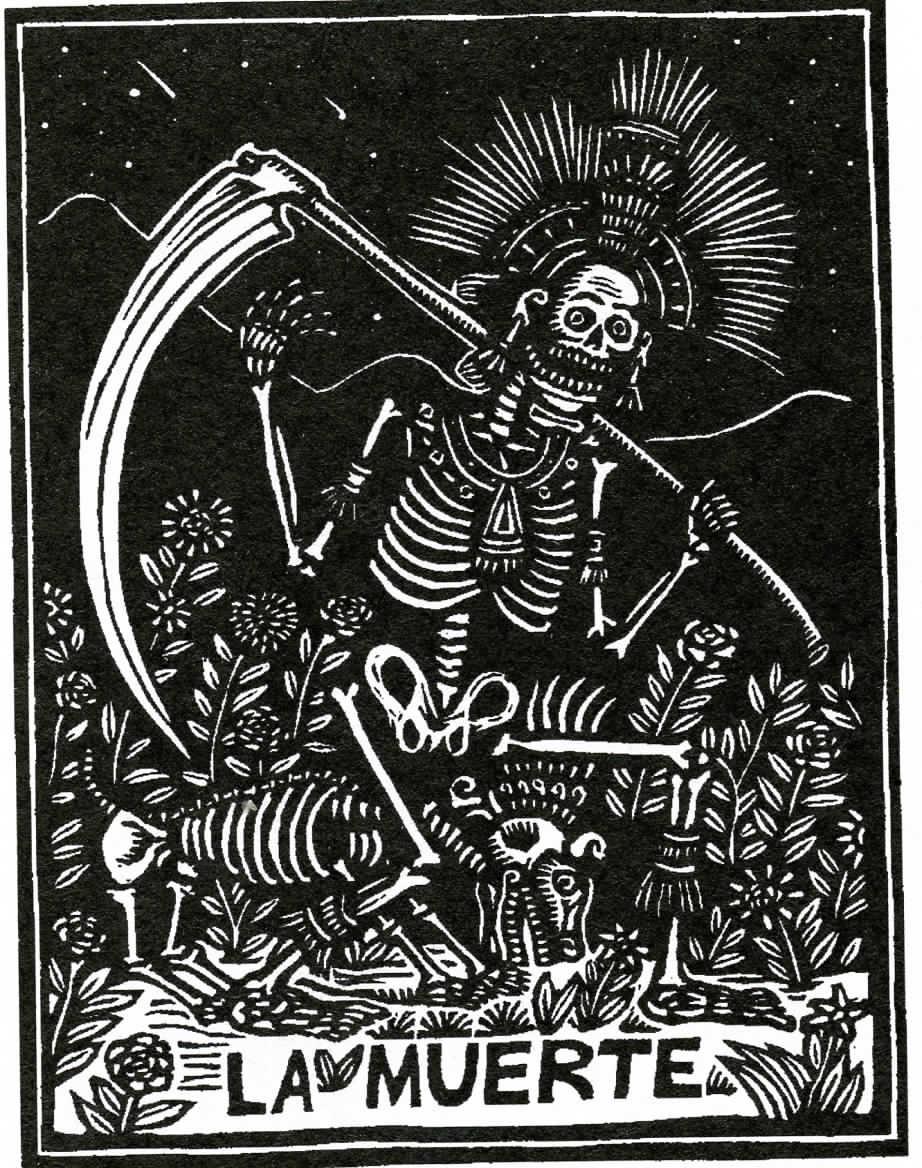

The images are really lovely and remind me of the work of renowned Mexican artist José-Guadalupe Posada. I found myself rushing through the poems, but lingering over the art. Some of my favorites are “La Muerte” (9), “La Mano” (47), and “El Diablo” (123). Artemio Rodriguez’s work will be what draws me back to this book again in the future.

The poems, however, fall short. Perhaps they appear pale compared to Rodriguez’s work, and maybe that is what Herrera wanted. Who knows? While the poems themselves didn’t pull me in the way I wanted them to, certain phrases here and there did. In the poem, “La Muerte,” for example, I was refreshed by Death saying, “it is in my nature to be generous” (8). That’s one way to think of death, giving, constantly reminding us how precious life is.

The poems and images seem to work in tandem best when Herrera’s words don’t resist sense too much, but instead create a narrative to support the image. The two that work best, in my mind, are “La Mano,” and “El Arcangel.” Rodriguez’s image depicts an over-sized hand that seems to be a large puppet. Two feet protrude at the opening by the wrist. The fingers of the hand hold a pencil that is drawing the sun in the sky, only  partially designed. Herrera’s poem tells the story of a “left-handed angel” that was “punished,” her braids turned to wings (46). Rodriguez’s image opens up to us in a compelling way through Herrera’s imagined narrative.

partially designed. Herrera’s poem tells the story of a “left-handed angel” that was “punished,” her braids turned to wings (46). Rodriguez’s image opens up to us in a compelling way through Herrera’s imagined narrative.

In “El Arcangel,” a fierce-looking angel is impaling a poor villager. The villager is reaching up towards the angel as if, moments before, he was supplicating him for aid. Herrera evolves the tale with a persona poem in which the angel hears the prayers of the villager:

So I arrived-you called,

you said candles and honey.

Your bed, your little water

jar of holiness . . . . (30)

The archangel, however, decides to answer these prayers in an unexpected way, by killing the man, and in this way partly responding to what the villager asked for:

you said,

too many years, lives

have gone down. So I said,

why not? I said, let’s

change up

the literature of the world. (30)

The archangel interprets the villager’s prayer in a way the villager did not intend. In this poem/image juxtaposition, Herrera manages to create an interesting dynamic and dialogue between the two.

Given the success of the images over the efficacy of the poems, I suggest ingesting LoterÃa as a kind of cautionary tale: be careful when incorporating images with poems. A delicate balance should be the goal, so that image doesn’t overwhelm text.

Also, choose treadmill reading with care, or you may end up with eyeball whiplash from frequent clock-watching.