Driving home from work, I turn to my husband and ask, “Isn’t everyone, to some extent, a sociopath?”

“Yes,” he answered. “We have to be to survive.”

A sociopath, according to Dictionary.com, is someone “who lacks a sense of moral responsibility or social conscience.”

So many paralyzingly awful things happen in the world, that in order to function, we necessarily filter how much we allow those things to affect us emotionally. We may numb our social conscience to some degree so that we can get out of bed in the morning, get dressed, go to work, earn money, eat, and ultimately survive. So that we do not fall prey to depression and lassitude, we paint over our consciences, many layers of paint, allowing thick coats of it to harden over our tender spots. Protective layering against the elements.

“Isn’t everyone, to some extent, a sociopath?”

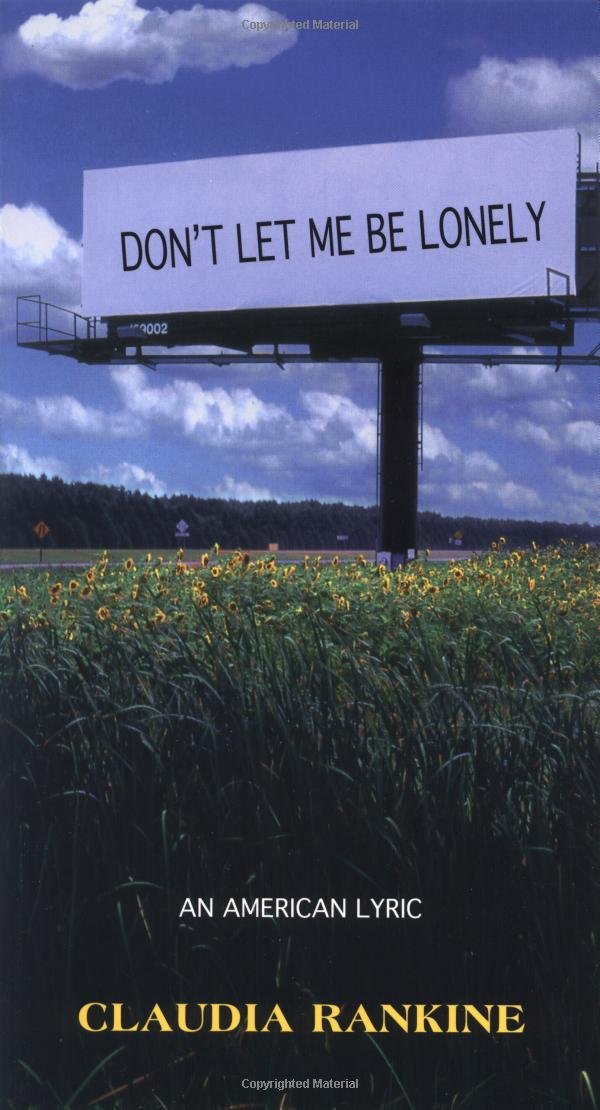

What has got me thinking about this question is Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (Graywolf Press, 2004). This book strings together pieces that straddle the genres of short, lyric essay and prose poem, lying somewhere in between. “An American Lyric” is the subtitle, and I learn from the back ocover that it is categorized as “Lyric Essay/Poetry.” The short paragraph form is inviting, as is the casual voice of the speaker.

But while the tone and form entices and lulls, the content is like solvent. Be warned: those protective layers you’ve carefully built up may be in danger of dissolution.

Rankine’s lyric begins in personal tragedy, the cancer and death of a friend, the car accident that kills her sister’s family; then moves gradually to larger scale tragedies, violent acts of racism, 9/11; and culminates with global tragedy: the invasion of Iraq, the rampant spread of fear.

Throughout the book, the speaker persistently inquires into the nature of loneliness and the value of life:

Define loneliness?

Yes.

It’s what we can’t do for each other.

What do we mean to each other?

What does a life mean?

Why are we here if not for each other? (62)

And the speaker seems to answer that ultimately we experience our griefs alone, and that the value of life, is doing what we can for each other. The value of poetry is in transcribing that grief and experience and offering it as a kind of bridge. Rankine writes:

Sometimes I think it is sentimental, or excessive, cer-

Sometimes I think it is sentimental, or excessive, cer-

tainly not intellectual, or perhaps too naive, to self-

wounded to value each life like that, to feel loss to the

point of being bent over each time. There is no innovat-

ing loss. It was never invented, it happened as some-

thing physical, something physically experienced. It

is not something an ‘I’ discusses socially. Though

Myung Mi Kim did say that the poem is really a re-

sponsibility to everyone in a social space. She did say

it was okay to cramp, to clog, to fold over at the gut, to

have to put hand to flesh, to have to hold the pain, and

then to translate it here. She did say, in so many words,

that what alerts, alters. (57)

So not only is Rankine’s work, then, a kind of solvent. She advocates Kim’s position that poetry should be a kind of paint thinner, helping to strip the distance between us.

Rankine’s text may leave readers emotionally raw, but not without hope. Her lyric ends citing Paul Celan. “I cannot see any difference between a handshake and a poem” (130). The offered poem connects the giver and receiver in a shared acknowledgement, an affirmation of each other’s presence. And this affirmation “has everything to do with being alive” (130). We acknowledge each other’s humanity in the deepest sense, collapsing our loneliness through the work of a poem.