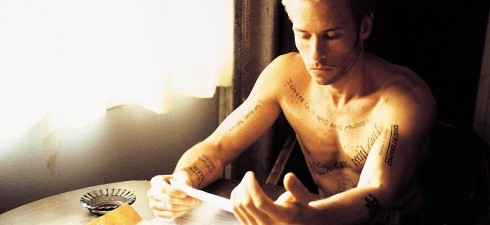

In the 2000 Christopher Nolan film Memento, the central character (Leonard) has a big problem with his memory. After an accident an indeterminable amount of time ago, he is unable to form new memories, and while he feels he has a good recollection of everything prior to his injury, short-term memories fade from his mind within minutes. Determined to avenge the rape and murder of his wife, he conceives of a system that will allow him to regain control and function within his almost impossible situation. By writing notes, taking Polaroid photos and annotating them with instructions for himself, and tattooing the most essential ‘facts’ onto his body, he wages war against his condition.

In a cafe, Leonard explains some of his rationale to Teddy, a suspicious man that keeps reappearing, with warnings and advice:

‘Memory can change the shape of a room; it can change the color of a car. And memories can be distorted. They’re just an interpretation, they’re not a record, and they’re irrelevant if you have the facts.’

One of the tattoos on Leonard’s arm extends this conviction: ‘Don’t Trust Your Weakness’. His system is a way of overcoming the unreliability of memory in relation to the material world: a prosthesis, to accomplish greater objective effectiveness. As the film progresses, it becomes clear that Leonard’s effectiveness beyond his subjectivity has made him a tool capable of accomplishing terrible and significant things. This rewiring of the frail, limited human subject into a killing machine reminds me of the projects of Nazism, in the extreme: it enabled the overcoming of the ‘weakness’ that made us human, to come close to destroying whole peoples, on someone else’s command.

On the other hand, medical science utilises the tools and abilities of brilliant minds, building on those generations before, to accomplish amazing good. The ability of the scientific method to comprehend and manipulate the material, observable world, has benefited all of us immeasurably. So here’s the challenge: we’re all faced with the invitation in life to understand and try to overcome our weaknesses, to change the world around us. But as we do, we need to make sure that we know who we’re working for. Our memory is short, and if our productive effectiveness exceeds our foundational understanding of the systems we use, we’re open to be manipulated ourselves. Whoever is providing the narrative worldview that we adopt, we can easily become a machine for their cause.

‘Facts’, it turns out, are messages left to us by another self. That self can be a former version of ourselves: though this may not be a better basis for our trust. As Dylan sang: ‘You’re gonna have to serve somebody’, and I want to know who that is, and what the moral implications are of the productive labour of my life. We’re all afflicted by a memory condition in life… so I’d like to hear from you, reader: do you see the limitations of human subjectivity as being a handicap? If so, what systems do you use to overcome your ‘weakness’? How do you gather your foundational ‘facts’? And how do you feel about your life’s work, and the ways in which we can, as a community, affect the world for the better?

;

First, great movie with a great review. Nolan is a genius–even his lesser films (Inception) leave me slack jawed.

Second, our limitations of understanding, whatever our system is (whether religion, political party, life philosophy, judicial procedure) should make us wary of thinking we can undertake judgments on the human condition that result in taking life. Circumstantial evidence in murder trials, for instance, is no better than Leonard’s system. We can convince ourselves we’re right, but time and again we find out we’re wrong.

I trust no system, only human frailty.

Ed, I agree about Nolan. I love his thematic interests… and with Inception, that was certainly what captivated me: not the narrative arc, which I found dull and frustrating. Even the plot of Memento, I found less interesting that its concept and quotable moments.

On taking life, you’re right – we can trust no system, and must be skeptical in the extreme. What about more widely, though? Is there a point where we need to let go of the active performance of skepticism a little in order to construct something with this life? I liked a description of James Wood’s recent book, by himself: he said that he ‘ask[ed] questions like a critic, and [gave] answers like a writer’. I wonder if we need to do this if we want to build?

I guess another way to put it is, pick any system you want (ie, the writer side), so long as you can articulate its limitations (the critic side). Or, we should understand skepticism as a kind of narrative/expression of life, not some kind of meta-narrative. Skepticism itself should always be subject to even greater skepticism.

I trust Logic, I think.. although it’s been a while since I studied that stuff properly.. but the thing is that most of the stuff we come to conclusions about in life are based on a premise being true that we don’t actually know is true and from this ‘maybe truth’ we infer lots of other things.. but if the premise isn’t true, and maybe our use of inference is wobbly too, then no wonder we get really mixed up.

I remember my favorie scene in the movie: Leonard is running through a parking lot after forgetting what just happened to him for the last 15 mins or so. He sees some guy running several car aisles away at about the same speed, and he wonders “hmmm, am I chasing him or is he chasing me?” Then the guy takes a pistol shot at Leonard. “Okay, he’s chasing me.” This kind of sums up most of the decision trees we erect in our brains.

This reminds me of a story from Pema Chodron that a friend recently shared with me:

And this, from Maria Lugone, who describes playfulness as a way to truly consider and explore the experiences of others: