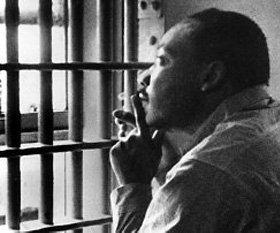

I am a college writing teacher and every semester, I assign my students the argument classic “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Dr. Martin Luther King, written in 1963 in response to Alabama clergymen who believed King’s visit to Birmingham under the auspices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference was unnecessary, unwanted, and illegal. In composition class, we discuss the letter in terms of his appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos. We examine both his rhetorical strategies and the larger context of the Civil Rights movement; and almost uniformly, students are gripped by his letter and deeply moved by the points he makes. Also, many of these young people comment that reading the letter is a history lesson for them, a glimpse into a long ago (to them) chapter of our national history, a chapter that feels cobwebbed and nearly ancient to those who grew up in the racially desegregated and diverse (though often still divided) South of the more recent few decades.

This semester, my mind has been on Ordain Women and the groundswell of support, contention, discussion, pushing back, pushing ahead, and the like that has accompanied the Mormon feminist movement(s) of 2013. So when I heard students making the expected comments about how much things have changed since 1963, I was struck by the realization that at least in our Mormon corner of the world, this letter is not merely a historical remnant of a brave leader and a powerful movement, but also a guide and a support and an articulate clarification of why action is sometimes needed, because Mormon feminists are still having to make their case for equality.

This semester, my mind has been on Ordain Women and the groundswell of support, contention, discussion, pushing back, pushing ahead, and the like that has accompanied the Mormon feminist movement(s) of 2013. So when I heard students making the expected comments about how much things have changed since 1963, I was struck by the realization that at least in our Mormon corner of the world, this letter is not merely a historical remnant of a brave leader and a powerful movement, but also a guide and a support and an articulate clarification of why action is sometimes needed, because Mormon feminists are still having to make their case for equality.

Let me be clear that I intend no disrespect to those who fought fearlessly and valiantly in the Civil Rights movement, nor do I mean to draw some kind of perfectly matched, criss-crossed analogy between then and now. Civil Rights advocates, both black and white, forged ground and prepared fields that later activists of all stripes have been able to plant in. And as such, the world of the Jim Crow south in 1963 is not the same world we live in today. Mormon feminists are mostly not having to fight for their temporal survival or for basic freedoms that had been guaranteed by the constitution but never observed.

However, despite the many privileges and cultural advancements that current Mormon feminists do enjoy, particularly, the ability to organize and communicate, there is still great ground to cover. In bald terms, our church is a place where women are often stifled and silenced, and though this closeting of women’s voices and views may not be intentional, the patriarchal structure as currently constituted is detrimental to both women and men and contrary to the path of discipleship taught by Jesus himself. Simply put, we have segregated women’s voices and power and insight.

In my opinion, that is. I don’t speak for anyone else but me. And sometimes not even that…

But back to why activists in 2013 should dust off a letter written fifty years ago. It seems to me that inside the strange and to-be-expected tangle of patriarchy, priesthood, and power in the church, we see some of the same tensions and tendencies that Dr. King so clearly identified in his world. And in our particular religious tradition, members exist in a kind of past-present state, living and worshiping in the 21st century world, but also living and worshiping in a kind of bubble of the past governed often by the mores and expectations of previous generations. As a deeply conservative (and not necessarily in the political sense) religion, we keep ourselves at arm’s length from today’s world, though we make sure not to lag much behind that length either. We are not the Amish, but neither are we the avant garde at the front of a movement. So for Mormons, and Mormon women in particular, it continues to feel like the 1960s in some ways.

Dr. King’s letter from the past can also serve as a reminder of the bright future that shines in front of brave visionaries who are not afraid to act. It also serves as a reminder of the response that awaits (and has already shown itself) to those visionaries. People are different now than they were in 1963. And they are also the same.

When the eight clergymen to whom he wrote his letter accused of him inserting himself into someone else’s business, Dr. King wrote, “But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town.”

When the eight clergymen to whom he wrote his letter accused of him inserting himself into someone else’s business, Dr. King wrote, “But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town.”

He continued, “Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states….Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea.”

Many Mormon feminists, especially under fire from other members, feel the same way, that we are all Latter-day Saints and should not be pitted against each other. The accusation that Ordain Women is somehow trying to tear apart the church by meddling where it doesn’t belong stings. There is great hope at the helm of Ordain Women, hope that just such “an inescapcable network of mutuality” could uplift both men and women of the church.

Dr. King famously laid out the steps necessary to foment change: “In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action….

“You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored.

“My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth…. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.”

In a church that so abhors contention as being of the devil that nearly any disagreement feels spiritually off, the idea that tension can be a positive force might itself feel off. And yet, as we study the wildly fascinating and remarkable history of our church, we can find instances of such positive tension scattered – like sunshine – throughout. Our contemporary church often feels like mostly monologue. Perhaps that is to be expected. But again, that perusal of our history reveals that many of the best and brightest moments of latter-day goodness were, in fact, dialogue.

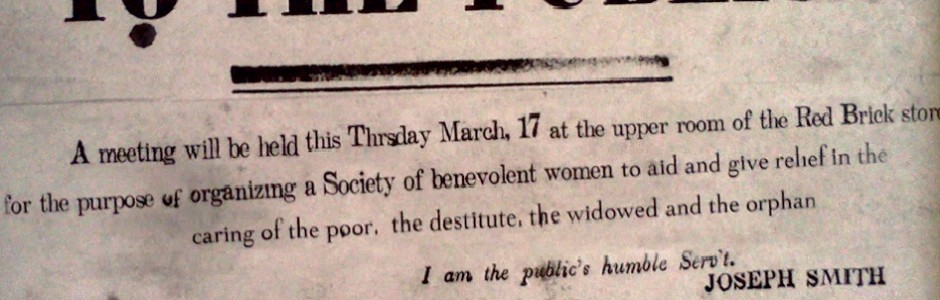

Later in his letter, King spoke a truth that I have carefully placed into my own personal canon. His words on the following subject are supported by Joseph Smith’s revelation in Doctrine & Covenants 121, also a beautifully poignant letter written by a disciple behind bars – “We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion. Hence many are called, but few are chosen.” From a similar vantage point as that forced on Joseph Smith in Liberty Jail, Dr. King recognized the damaging influence of power and concluded, “Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed….

“For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

The next part of his letter is especially heartrending. To directly connect what he describes as the horrible injustices known to all African-Americans of that generation (and before that and before that and…) to the painful experiences of Mormon feminists is an imprecise comparison and not one I am trying to make. Out of respect for the soul-crushing evils of Jim Crow laws, I want to speak carefully and avoid exaggeration. I will not claim that the world I was born into in 1972 or the life I was fortunate to be given with its educational opportunities, voting rights, and other advantages is anything like sad, trapped existences of those people for whom Dr. King rose up to lead.

But still, I am deeply moved by his words. And in his description of the twisted thinking of that era and the way such thinking crippled hearts, minds, and lives, I see a pattern that has persisted long past the Civil Rights movement heyday. It is a pattern that emerges whenever power is unequally distributed. And these resultant mind twists and the toxic side effects of such unequal power distributions are almost then – almost, though not quite – beyond the fault of those who hold the power because those power holders have been so deeply influenced by the power structure, they may no longer be able to see the world in any other way. And so it falls to others to stand up.

King attempted to lay plain the rotten fruits of the power structure with a personal example and wrote: “when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; …when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”–then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair.”

I hope it is not melodramatic to say that many Mormon women feel that “degenerating sense of ‘nobodiness'” in today’s church.

Not all women, no. Not all. But not none.

I am not necessarily pointing a finger of blame at the institutional church either. But our cultural church made up of the collective people and ideas and history seemingly has given all of the administrative power to men, sometimes in spite of doctrine, history, good sense, and scripture. And I do not think the current power distribution of the cultural church is in our best collective spiritual interests.

A few other moments from the highlight reel of this letter include Dr. King’s chastisement of those who may have considered themselves his allies, but who actually were greater obstacles in the march toward equality: “I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection….”

“I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that the present tension in the South is a necessary phase of the transition from an obnoxious negative peace, in which the Negro passively accepted his unjust plight, to a substantive and positive peace, in which all men will respect the dignity and worth of human personality. Actually, we who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.”

“I had also hoped that the white moderate would reject the myth concerning time in relation to the struggle for freedom. I have just received a letter from a white brother in Texas. He writes: “All Christians know that the colored people will receive equal rights eventually, but it is possible that you are in too great a religious hurry. It has taken Christianity almost two thousand years to accomplish what it has. The teachings of Christ take time to come to earth.” Such an attitude stems from a tragic misconception of time, from the strangely irrational notion that there is something in the very flow of time that will inevitably cure all ills. Actually, time itself is neutral; it can be used either destructively or constructively. More and more I feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than have the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation.”

Time itself is neutral? That was a mind-blowing thought for me when I first read this letter. And a thought that then blows out of the water the feeble platitude sometimes tossed at Mormon feminists that if they will just hold on, sit tight, and avoid rocking the pew, that things (unspecified but implied) will change.

It seems more accurate to say that if women just hold on, sit tight, and avoid rocking the boat, things stay the same.

One of the most beautiful aspects of Mormon theology to me is its ability to change and adapt, to progress and grow. And it seems in keeping with the peculiar character of our church for members to ask leaders to consider what’s next. I would not be surprised if some church leaders have deep hope that our members are readying themselves for more.

Dr. King explained to the Birmingham clergymen that while they thought his position radical and frightening, he actually eschewed violence; instead of violence, he promoted idea that “normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist. But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.”

Was not Jesus an extremist for love, indeed. This reminder infuses our collective resolve and clarifies our purpose.

Students of history know that the momentum of the Civil Rights movement was inextricably bound up in the power of the Southern church and the motivation of faith of many who sat-in or marched out. Still, there were those believers then who preferred the comfort of the status quo. I can relate mightily. To them, Dr. King said, “But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity…. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust....Is organized religion too inextricably bound to the status quo to save our nation and the world? Perhaps I must turn my faith to the inner spiritual church, the church within the church, as the true ekklesia and the hope of the world.”

While I actually believe that the organized part of our religious organization can be a lovely force for positive action, I am also roused by Dr. King’s reminder that it is our inner spiritual church – our inner compasses and consciences – that can lead us in the right direction. This might just be one of those times when we know the correct principle and now get to govern ourselves.

Regardless of a person’s stance on the ordination of women, I hope we can agree that honest examination of the status quo and a return to that sacrificial spirit of our early Saints who upended their worlds in pursuit of Zion will bring to us and us to hope as well.

;

Brilliant.

Thanks to you guys – Jennifer, Brett, and Marie! I’m glad it had an impact. I had quite an adventure getting this up… my first draft was lost and I had to think it all through again. But I am glad for an opportunity to really consider all of this. :)

What lucky students to have you as their professor, Erin!

I hope they think so! :) This comment mean a lot, Brett!

This is so impactful! Thank you for showing us all of these parallels.

Thank you for reading the essay – and sharing your response! :)

A lovely and thoughtful post. Thanks for writing it.

Thank you, Janell! :)

This is wonderful. I am printing it out and putting a copy in my journal. Thank you doesn’t quite cover it, but that’s what I have.

Thank you, Laura, for your kind words! I’m glad it was meaningful! :)

Wow! I love this comparison, Erin! This line in particular struck me:

“Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co workers with God,”

Progress looks inevitable in hindsight, I would guess, and that biases our vision of what it looks like when it has yet to happen. It feels so much less inevitable, so much less clear and obvious.

Great post.

I have thought about that same thing, Ziff – the appearance of progress on either side/end of it. Great point! So much of what people do requires a lot of faith…that the good thing worked for while come to pass. :)

Erin,

This was absolutely lovely and moving. You draw the parrallel compellingly and appropriately. Religion is one of the last major frontiers in the battle for equality for women (in the developped world). There are others, of course, but the structure of religious institution which so deeply affect the lives of so many is so important. May we grab onto our prophetic and utopian roots and be one of the religions to capture the vision of Zion in full. I hope this post because important in the ongoing public discussion within the church. It deserves to be. Thanks!

Thank you for your kind words. Yes, I love the idea of capturing that early vision of Zion! I think it is one of the most beautiful aspects of Mormonism, absolutely. :)

Erin, what a powerful essay. Your words (and Dr. King’s) and this comparison have inspired me. As I was reading, I felt such clarity in my mind and heart. Thank you. I’m going to share this, and I also like Laura’s idea of printing this off for my own personal records/notes.

I love that feeling of clarity! I am glad this essay felt meaningful to you. Thank you. :)

If we had female apostles, they would be advocating for gay marriage and other evil things.

Your comment is a complete non sequitur in my view.

This comment is a joke, right?

This is a very good essay. Thanks for taking the time to write it and to think about it. I hope lots of people read it.

What nice words! I am glad to be a part of the larger conversation. :)

Erin. I will be forever grateful to you for what you have written here. You are a talented writer, and this essay speaks truth to my very core.

You make the claim that what we as Mormon women have endured may not perfectly parallel the plights and struggles of those under who lived under the Jim Crow laws, but, I submit that it does. We have the luxury of perspective in our modern era where women may do just about anything but hold the priesthood to look back and say that we haven’t had it “as bad as they”. But, as women, if we dissect history into categories of “haves” and “have nots” women have invariably, until very recently, been lumped into the “have nots” of the world. I think the correlation and connection you have made between what Dr. King poetically and poignantly speaks of and what we as women deal with in our day (and days past) is absolutely parallel. It coincides completely.

For so long I have been a Mormon moderate. I believe in causes such as Ordain Women, but have been lukewarm in my approach and defense of it. That, as Dr. King states, is this cause’s (any cause’s) stumbling block.

Thank you, Erin. Thank you ever so much.

I am touched by your reponse! Thank you for sharing that with me here.

Oh thank you so much for this.

And thank you for sharing your response, Monica. I appreciate it. :)

That was very moving. And disconcerting. It really is shocking that his words can so easily be applied to the mormon feminist today. Thank you so much for sharing.

Disconcerting is a good word to use – I agree. Thanks for reading it!

I’m so glad you wrote this, Erin. Probably the most thoughtful and measured piece I’ve read on this issue to date. Well done, as usual!

Oh thank you, Laura! I am the first to admit this is a *big* question with all kinds of answers and opinions. I am glad this came across as measured – when/if I speak off the cuff, I almost always regret my answers. :)

Wow. I read your article. You are well versed in many pieces of literature. Being able to reason things out and use our intellectual faculties is important. However, when it takes greater importance than seeking knowledge from the spirit it becomes dangerous to the scholar.

I have never understood the desire or need for some Latter-Day Saint women to hold the priesthood. I personally feel equal to the men in the church without the priesthood powers in my hands. We believe in the LDS church that God bestowed the keys of the priesthood to Peter, James and John. Then Joseph Smith and so forth. God does His work with a certain order that He determines righteously.

I do not believe the more we are waiting for is at all connected to women holding the priesthood. The only “more” I have had in my mind was more scripture.

I do believe the writings in this article about Mormon feminism and Ordain Women is not many steps away from opposing the church and the Gospel all together. Reminds me of the flaxen cord analogy. Also of the frog in the pot of warm water put on the stove… I am saying that this falling away happens in small steps. Steps we may not often even see as steps.

May I say please be careful. The spirit is the speaker of truth. We can think ourselves away from the Gospel if we rely on our own intellect and not on the Lord Jesus Christ.

I appreciate the kind and careful response you shared, Julia! Thank you for reading the essay too. I definitely understand what a delicate issue this is. I also recognize that many wonderful people see things differently than I do. I have been sitting on this issue for awhile – and despite the hours I put into it, still think that some of the topic is best discussed in conversation. Thank you for sharing your thoughts with me. :)

Erin…Hugs! I felt impressed to share my thoughts with you, but wrestled with doing so. Thank you for making it a safe place for me to share.

Haha! Erin, no wonder you are a teacher of a persuasive essay class. We are not all the way on the same side of this issue, but this beautiful, thoughtful, insightful essay makes me wish we were. Thank you for challenging me to to re-examine my stance, my motives, my core beliefs. I admire you so much for your bravery. And your goodness.

So, I’m one of the feminist moderates that you seem to be making a plea to. I think that in the next life it’s a possibility women have the priesthood. I believe God the Father and God the Mother are co-creators, co-governors, and co-equal. But there are so many more things I want changed before we even face the priesthood issue. Truly a huge amount is out there to be done. I feel I have many reasoned, logical, persuasive arguments that have the chance of swaying ears, minds, and hearts. The problem is that I don’t have any opportunity to get to any of my ideas when having conversations because I spend so much time having to explain the difference between me and the ordain movement advocating for people to be tolerant of your opinions and not consider you apostates. I spend all my time convincing others I’m not ‘that kind of feminist’ before they’ll even listen to my ideas, and by then (after an hour) they’ve checked out and it falls on deaf ears. So I’m not for this ‘you moderates are hurting our cause’ argument. Because I surely feel the opposite way right back at ya. I’m on the front lines myself, every day looking for open hearts and minds willing to listen — and I am shut down every which way I look. I posted a blog post myself about this (andersontopia.blogspot.com) and this is my response to the topic (written in the comments of my post):

“..there are a few things at play that make advocating for social change withing Mormonism different. The most telling is 3 Nephi 11:29. The spirit of contention is not of God and leads men to anger and to contend one with each other. Peacefully walking to the conference center or around it is fine. But creating conflict and contention is not the Lord’s way. And when security is going to have to be called to remove women from the doors attempting to enter – yeah, that’s a spirit of conflict and contention.

My other argument is that social change happens when moderates are the face of the movement and the radicals are on the fringe. If Malcolm X had pushed too hard too far and co-opted and became the face of the movement; MLK Jr would have never been able to accomplish what he did. Malcolm X got attention and opened some minds, but was not the cause of change.

That is not the case with the Mormon feminist movement. The most extreme are the face of the movement and by mere self-identification others marginalize and dismiss everything I saw because I’m somewhat associated. The visceral reaction that most Mormons have to the label feminist is a barrier, and the ‘Malcolm Xs’ of our movement are building that barrier higher.

We’ll have to agree to disagree on this point. I see why you believe it, in theory it makes sense. But on the ground I think the context is different and in reality my experience has been the opposite.”

I know you want the conversation to continue and to create tension, but schnikeys can we start with the cub scout/activity days discrepancy? Because I can’t support you. It really does hurt the work I’m doing here on the front lines with all my friends and family.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QYlDLChzig