The second journey on this Highway. Let’s drive.

Part 1

Eraserhead is the experience of stripping away our received mythologies. The chicken on the table isn’t dead. The baby is perhaps a cow fetus. And Henry has to raise it – as far as he possibly can — and to the limits of his sanity. You recognise the cries: they are the same as a human child.

It is a projection of a face onto a world: the perplexed image of humanity onto an asteroid-bombarded and desolate planet. It is the visual projection of an unknown creature that comes out of the mouth.

Eraserhead takes its own set of surreal symbols and turns them into a new mythic landscape: where the industrial whistles and clanging of factories have become agents of relentless torment and alienation experienced by Henry’s body.

It is staring at an elevator for so long that it scares us. It won’t close its doors. It won’t go up.

Eraserhead creates a helpless creature resembling the brain and the spinal cord, or a sperm: and puts it on stage. The most essential parts of our biology: hundreds of millions of years back into our evolution. We are still, under our skin, controlled by these spongy bundles of nerves: fragile, helpless, temporary.

Finally, as an escape from all this into a kind of dream (within a dream): Eraserhead is the horrible revelation of heaven. The ‘lady in the radiator’ and her song are more frightening and haunting than the cold world Henry leaves behind, crushing underfoot the creatures that lie in the path of her trite dance.

Part 2

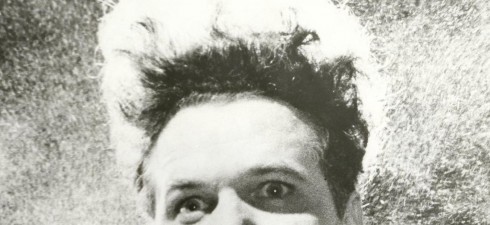

David Lynch took five years to make Eraserhead, due to the shortage of funding for the project. Family and friends helped, as well as a grant from the American Film Institute: still, filming was intermittent and Jack Nance ages visibly between scenes. However, Lynch made him retain the requisite amount of hair for Henry’s bizarre ‘do from 1971-76, promising him that the look would catch on someday.

In some details, Lynch has been happy to speak about the production of the film and its inspiration. He was open about the geographical basis for the urban landscape: it is modelled on the Philadelphia that Lynch lived in as a young man. Other aspects have become closely guarded secrets with strange speculation from fans growing up around them: as with the uncanny and horrific ‘child’ that Henry is left to care for alone. Viewers have been so disturbed and affected by those scenes that they wondered whether it could be a machine — or a distorted object from nature. The mystery has been preserved by Lynch and his team. He said that Eraserhead was his ‘most spiritual movie’, and the stories, silences and miracles of its production must be part of that.

Part 3

I helped teach a course on American Independent cinema last year, in which we looked at Eraserhead as part of a focus on Lynch’s contribution to the tradition that descends from Maya Deren and Luis Buñuel. Although the students had seen a range of innovative and challenging films that term, some of them couldn’t sit through the full 89 minutes. The film hits the viewer on a primal level, its effect bypassing the complex poetries and artistry that engages with higher thought. This film goes deeper: it grips you, and makes you want to look away. The class reported the tension felt in the group that reveals itself through laughter at the most disturbing scenes. Is Eraserhead, to any extent, a funny film? If it is, then it shows something of capacity to defuse the discomfort of perversity through laughter.

I remember watching the film again on my own, and being especially aware of the horror of the soundtrack. The long scene at the beginning of the film with the man in the planet, whose face turns very slowly towards the camera. I didn’t want him to look at me. The rushing I could hear contained trains, wind, water in pipes: and the sound of my own blood, pumping through the heart, the brain, the lungs. Later, the sound of the radiator, whistling louder and louder, attacked me: reminded me of the hallucinations I’ve sometimes had during bouts of high fever. Like in those fevered half-dreams, objects seem to take on the volume and intensity felt in the overheated brain. Inside the metal radiator, there’s a stage with a spotlight. Shining on nobody.

Eraserhead is a projection: in many senses. (Watch it in a cinema for another). Yet this is no criticism: it is entirely appropriate for the depiction of the troubled, post-industrial psyche. The mind invents itself through the overlayering of myth upon myth, to make our own fantasy of the world: the glasses through which we see everything. Yet behind all that lies something basic. Some things that are common to us all: the facts of our bodies.

NEXT WEEK: The final week of David Lynch, bring things up to date with Inland Empire (2006). For our schedule, check in here.

Drive indeed. Lynch is the master of lost highways, in’t he? BTW, thanks for including links to key clips.

I thought sperm as well, or a cross between sperm and fetus. I’m like, what the … And you’re right, I think, this is about what’s inside and our ancient selves. I came upon the same idea in the comments to my Scapegoats post. So many layers of evolution piled on top of that primitive element. And each of us experiencese the entire show in a lifetime, with the ancient appropriately lost in our ealiest experiences.

And that’s it really. What coud be more “spiritual?”

Well, that’s an interesting point you raise at the end there, Matt: where does ‘spirituality’ reside? I think I’d agree that the term refers to something pre-conscious… yet I’m not sure about the relationship between the primal level and the ‘spirituality’ that – even if it is preconscious – seems to answer some valency, some need that the primal level has. I do think that connection with the primal elements of ourselves is a very spiritual experience: because I think it’s only when we uncover the ancient self that we can feel these spiritual movements in their purity, divorced from all the higher-though, rationality-obsessed religion that so often obscures things.

Sometimes all it takes is a chance to bark at the moon. :D

Over thirty years ago, when I was very young, I rode my bicycle to a local college for a midnight showing of Eraserhead, and afterwards had to peddle the ten mile journey alone in darkness back home. I was not prepared, and remain forever changed.