As a girl, I spent a few winters rehearsing and performing in small roles in our local professional theater’s production of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. I can still quote large portions of the monologues (and many lines of dialogue as well) from memory. I loved everything about my experience there: the costumes, the other actors and actresses, the forbidden access to backstage areas and dusty nooks and crannies of the old theater, the excitement of opening night (which one year fell on my 13th birthday!) The story fit into (or contributed to ?) my somewhat nostalgic frame of mind quite well.

As a girl, I spent a few winters rehearsing and performing in small roles in our local professional theater’s production of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. I can still quote large portions of the monologues (and many lines of dialogue as well) from memory. I loved everything about my experience there: the costumes, the other actors and actresses, the forbidden access to backstage areas and dusty nooks and crannies of the old theater, the excitement of opening night (which one year fell on my 13th birthday!) The story fit into (or contributed to ?) my somewhat nostalgic frame of mind quite well.

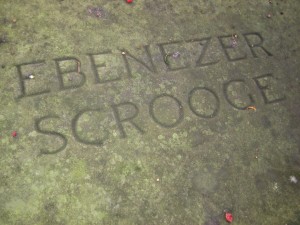

However, as an adult, I’m struck by the heavier themes in the story. I recently read the first chapter with my 6th grader who is studying the novel in her Language Arts class. We are introduced to Ebenezer Scrooge, a “tight-fisted hand at the grindstone,” who is visited by the ghost of his deceased business partner, Jacob Marley. Marley is ‘captive, bound, and double-ironed” in heavy chains he ‘forged in life’ by caring only about his wallet and the bottom line rather than serving his fellow man and using his resources to relieving suffering (yes, those quotes are from memory). It is Jacob Marley who has arranged for Scrooge to have the visitations from the three spirits that make up the bulk of the narrative and cause a the change of heart we are all familiar with.

As I was reading to Juliet, I was particularly struck by a paragraph I hadn’t noticed it before. As Marley disappears in a ghostly manner out the window, Scrooge looks out the window as he goes to close it.

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley’s Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to his ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below upon a doorstep. The misery of them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.

A particularly hideous and gut wrenching version of Hell.

or maybe he’s describing how we all feel. We see the pain surrounding us and its immensity shackles us because we don’t believe we have the power to interfere for good.

I like this interpretation, Mel. Sometimes I feel paralyzed by not knowing how to help, or knowing that whatever help I give will just be a drop in the bucket.

Cool insight, Mel. I just realized my post might sound a tad bit judgmental or off-putting. It wasn’t intended that way at all. I just wanted to share an insight I had. I think sometimes we become so familiar with something we don’t continue to see any new insights into it (until all of a sudden we do).

Claire:

Thanks for your insight. Your example reminded me of times I’ve read a familiar passage with or to someone else–or with commentary from someone else–and mined new meanings from the text.

Somewhere I’ve read that A Christmas Carol was written as response to the apparent pending demise of the yule-tide holiday. As such it’s something of a propaganda piece. I always loved seeing the musical as a kid but have not read the book. The musical (and now how many films?) certainly paints a dark picture of those who care for the world. I’d always been under the impression that this means to condemn avarice and other forms of “worldliness,” but Claire, this quote from the book really makes clear the Christian indictment against “arm of the flesh.”

As a born-again secularist I’m appalled anytime I see even humanity’s best attempts at doing good portrayed as futile and sinful — even hellish.