I’m not a movie critic, but I do see lots of movies. I’m not picky. I’ll see a “chick flick” that’s full of clichés and predictable plots. I don’t need movies to be realistic. That always seems like such an absurd criticism: “Oh, that movie was so unrealistic.” Umm, yeah: why would I want to see a realistic movie? No one’s coming over to my house to make a movie of my very realistic life.

But The Visitor (2007) stuck with me long after I’d seen it. To quickly recap, The Visitor is about widower Walter Vale (played by Richard Jenkins, in an Oscar-nominated role for best actor) who is lonely, disconnected and bored with his job, people, and life in general. We see him struggling to get through each day, firing his fifth piano teacher, and being obtuse and rude in his interactions with students and co-workers. Walter travels to Manhattan to present a paper and finds some squatters living in his apartment- immigrant couple Tarek (Haaz Sleiman) from Syria and Zainab (Danai Gurira) from Senegal. In a move that seems to take even Walter by surprise, he invites them to continue living in his apartment temporarily. I don’t want to include any plot-spoilers, in case you haven’t seen it, so I’ll just say that Walter becomes intimately entangled in Tarek and Zainab’s immigration troubles and steps out of his comfort zone to try to help them.

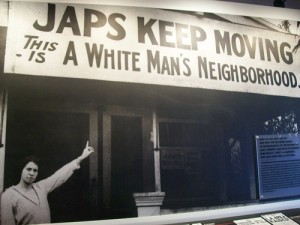

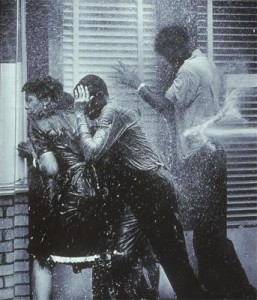

Some might see this movie as a critique of U.S. immigration policy. For me, this movie was more about what to do or think when institutions in which we have placed our trust fail us. For me, this movie tells a story about a way in which the United States government, as an institution, fails people like Tarek and Zainab (and Walter). I guess I grew up lapping up tales of American exceptionalism in school. I grew up placing my hand over my heart and singing “My country ’tis of thee,” followed by the pledge of allegiance in which we state “with liberty and justice for all.” But as I got older, I began to learn that in many ways, we haven’t delivered on that promise of liberty and justice for all. I slowly started learning about the many ways in which our country has failed and continues to fail marginalized groups. And now, as a parent, I’ve been able to watch my own children butt up against the gap between what we say we believe in and what we actually do. I’ve seen the genuine disappointment and confusion in my kids’ faces after learning about the Trail of Tears, the Japanese internment camps, the tragedy of the passengers of the transatlantic liner the St. Louis, the terrible abuse suffered by black activists during the Civil Rights Movement: I could go on.

My college students sometimes criticize me for being “too negative” about our country. I usually tell them that I think we get a lot of things right, but we blow a lot of things, too. The reason why I am so critical of things that institutions-like schools, governments, and churches-do is because those institutions are important to me, because they are powerful, and because they have the potential to do so much more than they often do.

I think there’s a fine line between teaching children (including my college students) to be grateful for the good things that institutions do and being honest and forthright about their failings. Several of my Black students have confided in me that they don’t recite the pledge of allegiance because they don’t believe the U.S. government lives up to what it promises. Many devout Catholics undoubtedly struggle to reconcile the sex abuse scandal with an institution that they otherwise love. I’ve read many blog posts written by Mormons who are similarly disappointed when they discover that the version of church history they have been taught is sanitized and selective.

So what to do? Do you trust institutions? Do you teach your children to trust institutions? Can you navigate prickly subjects and stories in a way that allows you to retain a love and respect for institutions while at the same time accepting their unfortunate and sometimes ugly actions?

Those are some of the questions that stuck with me long after ‘The Visitor’ was over. Beyond this, though, I loved the soundtrack. I loved watching Walter try to learn how to play the African drums. I loved learning the word “habibi”: an Arabic word that means “beloved one” (think “darling” or “baby”). I laughed when Tarek says they are running on “Arab time.” It reminded me of “Latin time” and the more obscure MST (“Mormon Standard Time”)-which is a lame excuse some Mormons invoke when they are unaccountably late. I love watching the unlikely relationship that begins to develop between Walter and Mouna (Tarek’s mother, played by Hiam Abbass, a beautiful Palestinian actress).

I read a movie review that said The Visitor was both heartwarming and heartbreaking, which aptly describes my feelings towards some of the institutions that I simultaneously hold dear and want to shame into living up to my expectations.

NEXT WEEK: We explore Truffaut’s vision of dystopian future in ‘Farenheit 451′ (1966). For a more extended schedule, check in here.

I’ve been meaning to watch this! Great review — some of the points you raised illustrate why movies, music and books are so important to me and why I see them as more than just entertainment. It is a way for me to grow in compassion and work through different sides of difficult issues.

The Visitor is a touching, thought-provoking film. I’m glad it motivated this post.

As modern humans, we do tend to place too much trust in institutions–and institutions always fail to live up to our idealistic expectations. Maybe it would help Mormons to quit bearing testimony that they know the church is true. Institutions can be efficient, they can be beneficial, but they cannot be true.

@Course Correction: I agree re: institutions being “true” or not. Talk about a sweeping claim.

But is some level of trust necessary with institutions with which we engage? Seems like it won’t work if we’re totally skeptical of them, either. Do we have to believe in their power/potential in order to help make good come about?

Love these reviews. And I LOVED this movie!

To answer your last question, I can. It takes work. But institutions are just a bigger system than a stake, or a family or a person. We, at every level, are imperfect.

Rachel, what did you love about it? I’m curious!

Well, your last line about heartwarming/heartbreaking is apt. I just enjoyed the story, and Jenkins is fabulous in this role. It is an opportunity to think about what you would do in a similar situation. We want to think we’d do the “right” thing, but the “right” thing is different things to different folks. This is set in New York in a post 9/11 world. Perhaps if you’d had loved ones die that day, immigration policy might seem reasonable. I don’t know. Absolutes are so hard.

I’m sure that probably isn’t a good enough answer for the professor, but it’s all I’ve got time to do for now–my children are clamoring for chicken curry for dinner. :D