Elder Jeffrey R. Holland gave an unusual talk–entitled “Lord, I Believe”–this past conference. I use the word “unusual” because it was compassionate, thoughtful (and thought-provoking), and faith-promoting. . . literally, it promoted “faith”–as in “belief” rather than “knowledge”, as in “I believe” rather than the more common Mormon assertion of “I know”)–as an acceptable spiritual stance.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland gave an unusual talk–entitled “Lord, I Believe”–this past conference. I use the word “unusual” because it was compassionate, thoughtful (and thought-provoking), and faith-promoting. . . literally, it promoted “faith”–as in “belief” rather than “knowledge”, as in “I believe” rather than the more common Mormon assertion of “I know”)–as an acceptable spiritual stance.

The talk was heartfelt, funny at times, and moving in places. The chatter in the Bloggernacle seemed almost uniformly positive. I chuckled at the comparison of dwelling on spiritual deficiences as a way to increase faith to stuffing a turkey through the beak . Here’s a YouTube link. Here’s a link to the conference page on the church website (Holland’s talk was in the Sunday Afternoon Session).

A lot of church members are uncomfortable with the emphasis Mormons place on spiritual certaintly. Many of these members, in my experience, seem to sense that their personal spiritual experiences–if they’re honest with themselves–aren’t enough to endow them with the same level of spiritual knowledge and unshakable religious conviction they perceive–often inaccurately–in other members (and church leaders). For many of these members, Holland’s talk, I suspect, felt like a warm hug. . . (like the hug Holland wanted to give to the young man that confessed that–if he were honest with himself–could only say “I believe” instead of “I know”).

[Quick aside: About half way through the talk Holland explicitly states this: “Let me be clear on this point. I am not asking you to pretend to faith that you do not have. I AM asking you to be true to the faith you do have.” This is a repudiation of Packer’s position–outlined in his infamous talk, “The Candle of the Lord“–that you SHOULD pretend to faith that you do not have, and that claiming to know something that you do not know is an act of faith that will be rewarded. Packer’s talk is on my list of The WORST Talks Ever. I was glad to see Holland taking a more sensible position.]

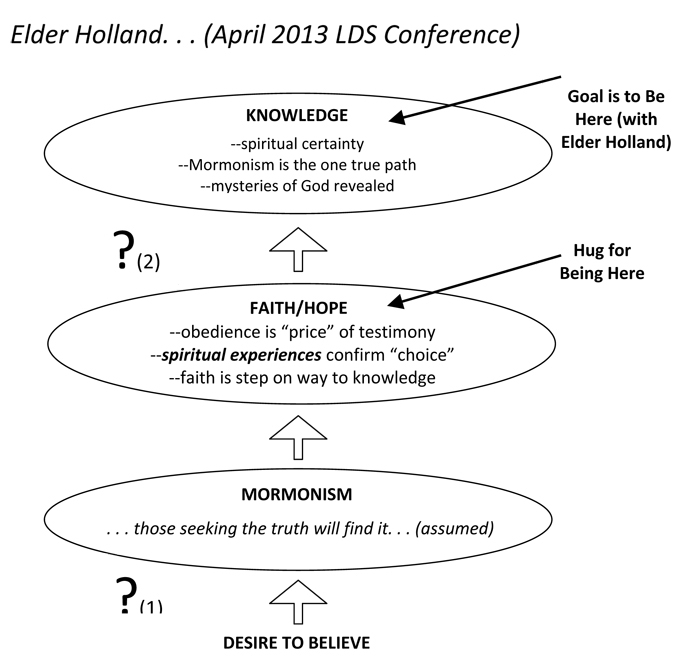

But (you knew a “but” was coming), even thought I appreciated the talk, there are at least two problems with it. In the first diagram (in the upper left), there are two question marks. The first question mark is next to the arrow that leads from a “A Desire to Believe” to Mormonism. Stop for second and consider this step. How does one get from a spiritual yearning to Mormonism? Think about the diversity of world religions. Think about culture and the way it is transmitted. Ponder the power of familial ties, socialization, the influence of parents, relatives, friends and family. Considered in this larger context, exercising a “desire to believe” will only lead to Mormonism if one is born into a Mormon context. The vast majority of the time, it will lead to other faiths. As Desmond Tutu put it:

“My first point seems overwhelmingly simple: that the accidents of birth and geography determine to a very large extent to what faith we belong. The chances are very great that if you were born in Pakistan you are a Muslim, or a Hindu if you happened to be born in India, or a Shintoist if it is Japan, and a Christian if you were born in Italy. I don’t know what significant fact can be drawn from this — perhaps that we should not succumb too easily to the temptation to exclusiveness and dogmatic claims to a monopoly of the truth of our particular faith. You could so easily have been an adherent of the faith that you are now denigrating, but for the fact that you were born here rather than there.”

Leaving out this complexity is the first problem with Holland’s talk. It’s a relatively minor sin of omission. The second problem is more serious.

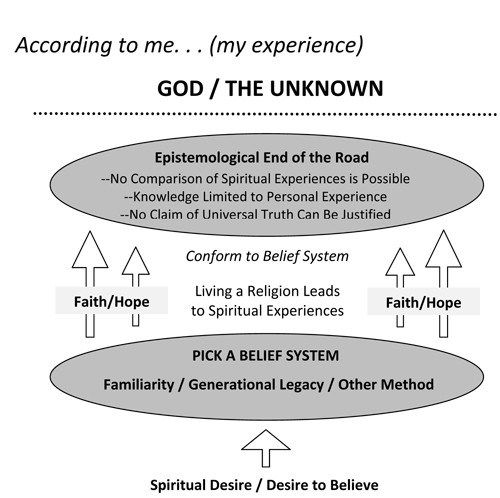

What happens when individuals–as an act of faith–choose to accept and live a religion? As Mormons, we know what happens inside Mormonism. Living the religion often leads to spiritual experiences, a sense of belonging and purpose, and sense of communion with fellow members. These are positive things. For many members, these outcomes confirm the validity of their choice–their act of faith–to live the Mormon faith.

This brings us to the second question mark in the diagram in the upper left (and the second problem with Hollands talk). What do the positive experiences of living the Mormon faith mean? What conclusions should a devout Mormon who has personally experienced the positive results of Mormonism–spiritual experiences, sense of belonging and purpose, and a sense of communion–reach based on these outcomes? A good way to answer this question is to ask what happens to the 99.9% of other human beings on the planet who choose to exercise their faith–their desire to believe–and choose to accept and live other religions (e.g. Lutheranism, Adventism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, etc.)? As it turns out, adherents of other faiths experience the same things Mormons do (spiritual experiences, purpose, communion). What should the hundreds of millions of adherents of other faiths conclude from their experiences?

Although Holland spoke compassionately about belief, he was clear what the “real” goal is–it is spiritual certainty (and he held himself up one who has successfully reached that place of certainty). There is a wide chasm, however, between choosing to live a religion and claiming to have absolute knowledge that one’s religion is the only “true” or “valid” path to God–and this chasm can’t be crossed based solely on one’s own experiences. Because individuals can’t directly compare spiritual experiences, and therefore have no reliable method for determining if one religion (or religious experience) is “more true” than another, faith is the last subway stop. The train doesn’t go any further.

I liked the story about the 14-year-old boy that hesitantly admitted to Elder Holland that he couldn’t say–yet–that he “knew the church was true” (but that he believed it was). Holland’s response was profound: “I told him with all the fervor of my soul that belief is a precious word, and an even more precious act, and he need never apologize for ‘only believing.’ I told him that Christ himself said ‘be not afraid, only believe.'”

I wish Elder Holland would have stopped there.

Or, if he felt he had to say more, I wish he would have said this: “Don’t let anyone tell you that belief isn’t enough. Belief is not a consolation prize. It’s not a stepping stone to certainty or knowledge. Belief, by itself, is beautiful and complete. Belief, my son [putting a hand on the boy’s shoulder for emphasis], is all there is.”

In an early A Mormon in the Cheap Seats post, I asked these questions: “Can a religion be built on faith? Just plain faith? Faith that isn’t looking for a promotion, or a pay raise, or that isn’t on its way to becoming something else?” I don’t know the answer to that question. I do know that the underlying epistemology of Holland’s talk isn’t the way I experience religion (see the second image below).

Well reasoned. Two points: isn’t it possible for one person to compare her own experiences with different faith traditions — spiritual experiences included — to make an individualized assessment of their relative merits? While we’re generally trapped in our own context, the context itself need not be (cannot be, at a micro level) static, right?

Second point is a nit: last sentence of area graph 4 “Ballard” should be “Holland,” right?

Thanks for catching that nit.

Can one person compare their own experiences with different faith traditions? Absolutely. It’s pretty common in the church to hear someone say “I’ve looked around, I’ve looked at other faiths, and that’s why I know Mormonism is true.” That’s a variant of the more common “I wanted to know for myself, so I prayed, and now I have my own testimony.” Two problems with the what I call the “individual search” claim: a) in order to do an effective search, one would have to really immerse oneself in different religions, live them for a period of time, study the religious texts, etc. and that would take years for each religion, so the search is going to be narrow by definition, and b) individuals are biased, they bring all their experiences to the table (e.g. someone who was raised Mormon that has “tried” other religions is like someone who’s grown up eating their grandma’s apple pie for 20 years, and then decides to go out and sample a few other pies, and then, surprisingly, discovers that their grandma’s pie is the best). So in the end, the individual is left with their individual experiences (and all they can say is that in their experience, this faith tradition is more valuable to them, etc.).

This is all well and good (Holland’s talk) and I find this relevant to my own journey. The problem is this, to me it reduces religion to nothing more than a cultural phenomena and life style choice that has little or nothing to do with claims of guidance and direct intervention by a God that has a special relationship with and personal interest in one’s religion. When I converted, I did so based on the testimony of others and I came in with the understanding that I would discover that it is the true and everlasting church restored to the earth through Joseph Smith. And that for one to achieve the highest degree of glory required the adherence to and the successful implementation in one’s life the laws and ordinances (full obedience) as defined by the Mormonan church. Based on what I have discovered about its origins and truth claims I am now skeptical as to the veracity of the church. If it is nothing more than a culture than the immutable demands and ideologies of the church seem archaic. Why should I continue to give my energy and resources to an organization that is self delusional, regardless of the good it does while ignoring the bad.

Bill, I agree, the church routinely makes truth claims that cannot be defended in my opinion. . . belief is one thing (and people–and communities–can believe whatever they want, of course) it’s the claims of absolute knowledge that are the problem. . . but, as I wonder aloud at the end, it may be that those truth claims are critical to motivating people to donate resources (money, time, etc.) and have therefore contributed to making the church as successful as it is (as a institution and as a collection of corporations with $30 billion in assets)

Brent from my perspective the truth claims and resulting authority and power paradigm created by those truth claims are absolutely essential to the financial success of the church and the commitment members exhibit towards it. That is why for me the veracity of the truth claims is not a negotiable point. I will not subject myself to authoritative control built on a fraudulent claim. To do so is to buy into the notion of the means justifies the end. As is so often argued, look at all the good and how it has helped you in your life. This notion has lead to some of the greatest atrocities in human history.

Brent, thank you for your MCS posts. I have read every one, and they really resonate with me. I hope you’ll keep writing, even though you were only going to do 50 posts. :)

Brent,

You are my favorite blogging. Please keep writing.

I appreciate your thoughtful analysis of Holland’s address. I found his remarks a bit less smug than most conference talks, but didn’t carefully analyze the problem.

Two problems with the what I call the “individual search” claim: a) in order to do an effective search, one would have to really immerse oneself in different religions, live them for a period of time, study the religious texts, etc. and that would take years for each religion, so the search is going to be narrow by definition…

Yup, I agree that a meaningful understanding of something as broad (and hopefully, deep) as a worldview or religious perspective requires both dedication and attention sustained for years.

…and b) individuals are biased, they bring all their experiences to the table (e.g. someone who was raised Mormon that has “tried” other religions is like someone who’s grown up eating their grandma’s apple pie for 20 years, and then decides to go out and sample a few other pies, and then, surprisingly, discovers that their grandma’s pie is the best). So in the end, the individual is left with their individual experiences (and all they can say is that in their experience, this faith tradition is more valuable to them, etc.).

This I find less persuasive because it proves too much. It is a good reason to be skeptical of every conclusion of every kind, including itself. Do I agree that our views are affected by our past and present conditioning/experience? Yes. Does that mean that I ought not draw conclusions because of the those effects? No, not to my way of thinking. The lesson I draw is not that the comparisons and conclusions are not worth making, but only that I should hold them lightly and provisionally, checking and rechecking them against the data available to me at any given point in time.

Disagree?

Sean, I appreciate your points, and I think we are in agreement. I should clarify that I’m not suggesting the individuals shouldn’t reach conclusions–and I like that way you put it “lightly and provisionally.” Individuals can (and probably should) reach all sorts of conclusions, for example, this religion is better for me, or I feel more spiritually connected when I do this or that, or based on the spiritual experiences I’ve had, I believe this, etc. By arguing that individuals are trapped by their own experience, I’m only questioning the justification of standing up and saying, “because I’ve had this experience, I know that everyone else’s spiritual experiences are less valid than mine, because I have the truth.” It’s the “universal” claims that lack justification. . .

Great post, Brent.

I think the problem may also lie in what Holland asked us to “believe.” In the Church, that belief tends to be doctine/dogma driven. I believe in God. I believe that Joseph Smith saw God. I believe the Book of Mormon was given to Joseph Smith by Moroni, and that the former translated it.

Recently, I wrote down my current beliefs, a self-examination of where I am religiously as I have distanced myself from the literal claims of the Church. My quick-sentence beliefs consisted of statements like…I believe in respecting others’ beliefs. I believe that it’s okay not to “know.” I believe in finding my life purpose. I believe in helping others and leaving the world better than I found it.

I’ve wondered why I didn’t LOVE Holland’s talk (I definitely liked it), and now I’m seeing why. The belief (vs. knowing) that he asked for still centers itself on LDS theology that doesn’t resonate with me even from an “I hope” perspective.

Often religion asks us to believe in its version of god (commandments/doctrine/obedience), and then hopes the byproduct to be an improvement in how we interact with humankind.

Why can’t religion ask us, more often, to believe in treating humankind more ethically and tolerantly, and hope that THAT leads us to God?

God is the author of our religion. We don’t have to hope to be led to Him. He has laid out the path. You just have to follow it.

Thatcher: “the” path? I think you missed the point of the post?

Such a great comment, Blake.

I love this question: “Why can’t religion ask us, more often, to believe in treating humankind more ethically and tolerantly, and hope that THAT leads us to God?”

I am making my way through thomas Riskas book “Deconstructing Mormonism” now for the 2nd time, and think he would largely agree with your assessment here of Holland’s talk. I think your analysis here is a good start. From today’s religious leaders it appears to me to be all about believing in belief for belief’s sake. Somehow the theologians think belief is far better and important than thinking and analyzing through ideas. Joseph Smith never thought that way. Brigham Young certainly didn’t appear to. Somewhere along the line, the obedience/believe what we tell you without testing it for yourselves has come to the front and they teach that more stringently than anything else. Thanks for the analysis.

Great post. Thank you.

Aaron B

The one thing you are forgetting in your analysis is that the LDS church teaches that people who do not find the “true” church in this life will have it presented and offered to them in the spirit world. So it is not essential that every person find the truth. However some are born into the religion. It is not clear why God does this, but it probably made sense to us in the pre-existence and will make sense to us after this life. Why is faith a requirement? Because it is a power we need to develop in this life. The Bible says that faith played a role in the creation (i.e., organization). Many people are led to the LDS church by the Book of Mormon. Two good books about this are “Converted to Christ through the Book of Mormon” and “Stories from the early saints – converted by the Book of Mormon”. While some people have miraculous conversion stories, most people have to go by faith. We walk by faith. That is how it is suppose to be. If we are faithful long enough, then like Elder Holland, we too can have a more sure word of prophecy.

The safer more realistic way is to walk by knowledge, acknowledging our fallibility, of course. Faith is a cop out and is invoked only when there is no reason to believe an assertion. But if there is no evidence or reason to believe, why does faith make up tyhe deficit? It doesn’t. Theologians have taught it does, but on closer viewing it simply falls short every time.

Brent, while your analysis of Elder Holland’s talk is interesting, it seems to lack some connections, important ones in my mind, especially in the LDS church. One extremely important thing that you don’t mention is revelation. That’s frequently enough in the conference talks (topics on revelation). I do believe there are steps from hope to belief/faith to knowledge — well, in fact there are these steps. This is covered in Alma. On the faith side, one of my best experiences was at school, hearing the then well-known T. Edgar Lyon (a high-council member) bear his testimony, which he started out with by saying, “I have an abiding faith in the truthfulness of the restored Gospel”. What a wonderful statement for a questioning 19-year-old to hear! It really resonated with me, and this was the fellow who had so many other experiences. Since then, I’ve shared that from time to time in testimony, because while I have progressed to knowledge and certainties, my abiding faith has also stayed with me. I was also fortunate to be around as stellar an intellect and faith as Dr. Henry Eyring, a quite remarkable scientist, member, and individual.

In your second diagram, the questions of “universal” truth. While I agree that it’s hard to compare what are essentially internal-landscape experiences, there are by now about 180 years of members sharing common experiences. Kneeling as a presidency and each getting the same answer is something. Kneeling as a husband and wife and getting the same answer is also something, something that strengthens and is also something along that process from belief/faith to certainty.

One can certainly deconstruct the system of belief, and of LDS belief, but to me these questions of “how to get from here to there” have been answered. There are processes one goes through. There’s a sort of dance with the Holy Ghost as we get familiar with that entity, and as it progresses, we learn to recognize its distinct and unique voice. How others experience it I don’t know (how do other folks experience the visual color red?), but by observation of other key indicators along with the others’ acknowledgement of the Spirit indicates that regardless of how others experience it, we are on the same page.

What’s further interesting, in my own personal view, is how the evolving and developing view of the universe meshes so nicely with my own perspective of the Gospel, and my place in this universe. The four fundamental forces, the sub-atomic universe of particles, the nature of matter, of particle physics, nuclear reactions, stellar fusion, gravity. One can certainly call it simply the anthropic principle, but I think it’s more — much, much more.