You, the audience, look through the barrel of an assassin’s rifle at a circular white space as a smartly dressed gentleman strides into view and then he suddenly whirls toward you, his now unconcealed pistol firing. A crimson wash of blood slowly coats the screen as the rifled steel tube waivers and fades to the side. So begins each of the 22 “canonical” cinematic treatments of the adventures of James Bond, British secret agent 007, a scene that elicits an expectation of exotic locales, glamorous females, dangerous adventure, ample sex and carnal wit.

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

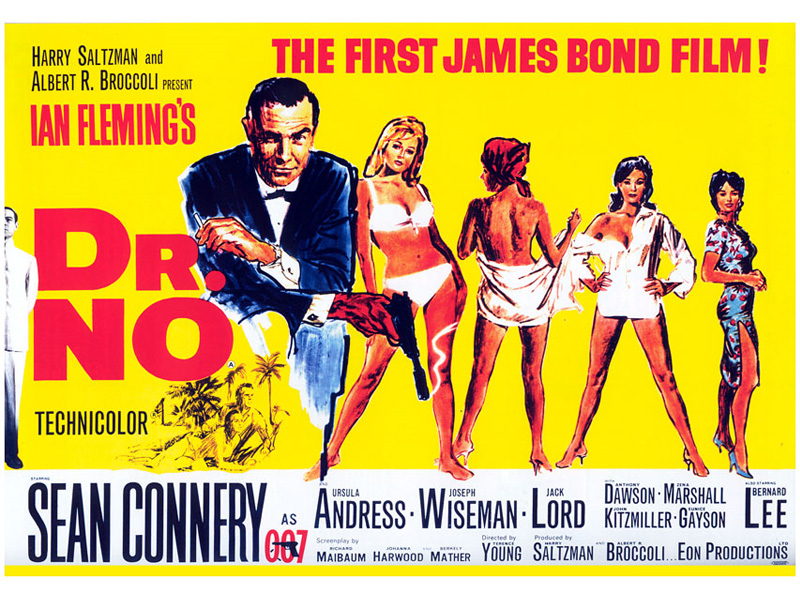

I thought about this iconic segment once again over this last July 4th weekend as I watched “Dr. No,” the first major 007 film starring Sean Connery, with my 15 year old son. He had never seen a retro Bond movie, so I dutifully warned him about potential scenes exhibiting outdated notions about gender roles and race, as well as the slower pace and often clumsy special effects found in these older films. Pausing the DVD, for some reason we discussed at length the rifle pointed at Bond in that opening shot–why is the audience looking at him from inside a barrel? Wouldn’t it be more natural to have us watch him through the crosshairs of a rifle scope? And, just exactly how does the blood from our gunshot wound seep so deep inside this gun barrel, obscuring our field of view, or more likely, the field of vision of … the bullet?

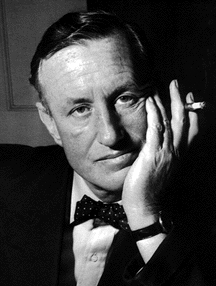

The week before I had just finished listening to Ian Fleming’s novel of the same name and from which this movie was derived (which is not always the case) on my i-Pod during my work commute. Ignoring with some effort the often blatant sexism and racism in this novel of the early 60s, I was pleasantly surprised by Fleming’s jaunty writing style, his knowing detail, the swing of his self-assured narrative and the distinct lack of utterly preposterous plots and the innumerable sexual innuendoes and gadgets that plague the later Bond films, the exaggerated movies of the Roger Moore era. I suspected, however, that the superb narration by Simon Vance made Fleming’s writing sound better than these words would read on paper, so I went to Barnes & Noble and purchased a collection of James Bond short stories (didn’t know they existed) by Fleming under the title Quantum of Solace. I was delighted to find the prose on the paper was as suave as James Bond on the screen. No wonder JFK liked them so much–they were nearly . . . dare I say . . . literary in their renderings, if often barbaric in their cultural understanding.

My favorite, although not the best narrative, in the collection is “007 in New York,” a piece written by Fleming for a non-fiction travel book. The story, ostensibly centered on Bond’s scheduled meeting with a fellow spy in NY, meanders into descriptions of local color and ends on a humorous note. The most intriguing bit, however, is the following recipe featured in the narrative itself which gives one, perhaps, the best sense of Fleming’s jaunty writing flair:

;

“Recipe for Scrambled Eggs ‘James Bond’:

For four individualists:

12 fresh eggs

Salt and pepper

5-6 oz. of fresh butter

Break the eggs into a bowl. Beat thoroughly with a fork and season well. In a small copper (or heavy-bottomed saucepan) melt four oz. of the butter. When melted, pour in the eggs and cook over a very low heat, whisking continuously with a small egg whisk.

While the eggs are slightly more moist than you would wish for eating, remove pan from heat, add rest of butter and continue whisking for half a minute, adding the while finely chopped chives or fines herbes. Serve on hot buttered toast in individual copper dishes (for appearance only) with pink champagne (Taittainger) and low music.”

Thinking back on my cinematic discussions with my son, I wonder whether I was forceful enough in my critique of the many offensive underlying values and assumptions present in the James Bond movies of past and present. Why didn’t I continue analyzing each scene in as much detail as I did the opening rifle barrel shot? Am I fooling myself, thinking that I have the ability to dissect each scene to disclose any latent sexism and racism, when I may not possess sufficient self-awareness to uncover and deconstruct the more subtle concepts hidden in the film? Did I betray my moral position on these important topics by actually showing the movie to my son, indicating some kind of tacit approval, or by doing so together with him were we able to watch it the way I watch the TV series “Mad Men,” enjoying the production values, acting, costuming and plot, all the while recognizing and turning away from the sins of our societal past? Or did James Bond, and all that he stood for in the early 1960s, shoot us first before we could shoot him?

My children are still a little young for James Bond, but I have these questions about video games, Barbie movies and Disney princesses. I think it is unwise to avoid them altogether and create forbidden fruit, but I also wonder if deconstructing is enough. Last week, I caught a showing of Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” at our local theater. In my late teens and early 20s, I watched the film many, many times — aping mannerisms, absorbing the style — smitten with the whole thing. It was interesting to watch it again, to see how much style there is over substance and I found myself alternately still seduced by it, particularly by Jean Seberg’s doe eyes (the camera loves her face and it is hard for the audience not to feel the same way) and Jean-Paul Belmondo’s gleeful tough guy — and a little embarassed by its pretension and sexism. It is not that I hold Godard to my modern-day standards, but I’m also aware that I absorbed some of the film’s ideas about what is cool, beautiful and sexy at a time when I had fewer filters and some of those ideas are still with me.

Heidi, I think you are correct that deconstructing may not be enough, but I guess I’m going to keep trying. I actually just got back from driving my son to camp where he will be a counselor in training and we discussed Bond quite a bit during our 2 hour drive. Most of our discussions were about the different movie versions and I pointed out that the films themselves have adapted over time and the producers have at least tried to speak to our culture’s improving sensibilities, although not always successfully. I pointed out that during the later Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig 007 eras, Bond’s boss called “M” is played by that wonderful feminine dreadnought, Dame Judy Dench, a powerful Margaret Thatcher of a woman, someone unafraid to say to Bond: “007, this may be difficult for a blunt instrument like you to understand, but . . ..” In one Brosnan Bond film, 007 gets a short lecture from Moneypenny about sexual harassment. In the latest Bond movie, “Quantum of Solace,” Bond doesn’t even sleep with his female co-star, a trained former operative who drives 007 through not just 1, but 2 car chases, a woman fiercely capable of holding her own throughout the film.