History, fantasy, reality, destiny. There are more similarities between these realms than there are differences.

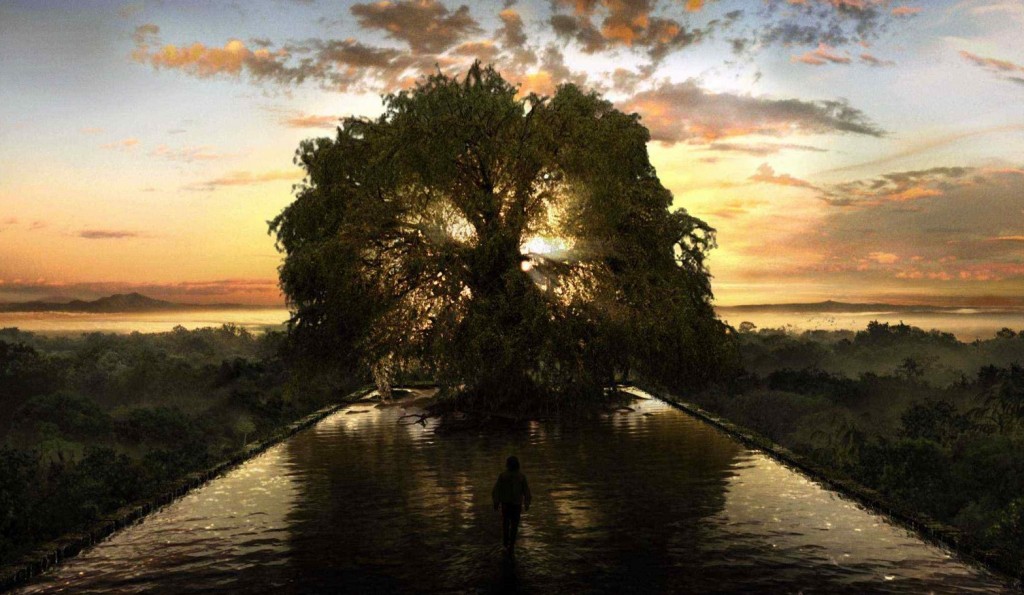

The Fountain (2006) situates one man, Tommy Creo (Hugh Jackman) in and between these stories. As an experimental medicine scientist, Tommy struggles to find a cure to save his wife Izzi (Rachel Weiss) from her terminal cancer. Before her death, she hopes to complete her novel : a story about the search of a Spanish conquistador for the Tree of Life: a quest that he hopes will save the Spanish Empire from destruction at the hands of its enemies.

While testing on monkeys in his lab, Tommy discovers a substance from a piece of South American tree bark that seems to reverse ageing. However, despite his hopes, at first it appears to not affect cancer cells. Meanwhile Izzi’s health fades rapidly, moving closer and closer to death, while accepting her fate with remarkable composure. In her hospital bed, she asks Tommy to finish the final chapter of her book.

In an earlier scene, Tommy finds Izzi sitting outside with a telescope, pointing up to a nebula: a cloud of dust where, she tells him, the ancient Mayans believed dead souls go to be reborn. In a future reality, we see Tom, who in a bubble-shaped enclosure travels to this nebula with a tree that seems to contain the life of his wife. He tells her that they’re almost there: if they can reach the nebula in time, she could be saved.

The three narrative frames of The Fountain are woven together, emphasising the power of history and fantasy in forming our myths and hopes about death and life beyond it. Into each of these frames, Aronofsky writes a number of different mythological structures: the Christian story of the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden, the Mayan myths of blood sacrifice and life, a meditative practise and the scientific search for truth. The synthesis points to something within each: something in common that lies behind all forms of human belief and scepticism.

* * * * *

Helen (my wife) and I watched this film together, and both felt quite differently about it (as is often the case). She has a brilliant scientific mind, and I’m an English Literature graduate: our personalities also cause us to look at similar things from different perspectives. Where Helen saw the victory of the film’s finale at the nebula (a representation of the sublime if ever I saw it), I was left with a sense of the sadness of the film: that all mythologies, including the one constructed by Aronofsky in this film, are inadequate for the part of us that desires individual immortality and the persistence of consciousness.

After making love, Izzi tells Tommy that she wants them to be ‘together forever’. This longing, Mormons believe, is something natural and essential to all people, and uniquely provided for in LDS theology. Helen and I have been ‘sealed’ to each other and to our families in a uniquely legalistic ceremony that promises to secure the substance of the desires that The Fountain expresses.

I can’t imagine how I will feel when the time comes for me to face being parted from the love of my life. I’ve only spent less than 5 years with Helen, but I don’t want to even consider how I could face day after day without her. I also acknowledge the eventual moment (less frightening for me: but more incomprehensible) when my consciousness will fade out. I will cease to be, at least, in the form I now understand. The chemicals that make up my body will live on in trees and animals and the air: but I will probably not know it. Helen will be part of this same beautiful earth, but we will be unaware when the atoms that once formed the muscles of our hearts, by some chance, find themselves briefly blooming in the petals of the same flower, or even, through a chain of transfers, coincide within the miracle of a new human foetus. I understand that the vast majority of me will remain after death: but I admit that I’m rather attached to the fragile chemical and electrical signals that flit in my brain, which I call ‘consciousness’.

I can’t imagine how I will feel when the time comes for me to face being parted from the love of my life. I’ve only spent less than 5 years with Helen, but I don’t want to even consider how I could face day after day without her. I also acknowledge the eventual moment (less frightening for me: but more incomprehensible) when my consciousness will fade out. I will cease to be, at least, in the form I now understand. The chemicals that make up my body will live on in trees and animals and the air: but I will probably not know it. Helen will be part of this same beautiful earth, but we will be unaware when the atoms that once formed the muscles of our hearts, by some chance, find themselves briefly blooming in the petals of the same flower, or even, through a chain of transfers, coincide within the miracle of a new human foetus. I understand that the vast majority of me will remain after death: but I admit that I’m rather attached to the fragile chemical and electrical signals that flit in my brain, which I call ‘consciousness’.

I’d like to hear from the readers of ‘Rogue Cinema’: how did you feel about the beautiful puzzle of The Fountain? How much recompense can mythology — or even the scientific comforts of persistence of the body — provide in the face of human yearning? Also: if my readers would be happy to share their feelings about the LDS theology of eternal marriage or their ongoing personal experience of the ‘sealing power’: I’d love to hear from you.

These stories are real. Aronofsky eschewed CGI in The Fountain in favour of extreme photography (for example, macro shots of bacteria and water) to show us a mythology in real things, and I consider much of religious mythology to be the same. Not literally, but metaphorically, the LDS stories about death and love speak truth. If they didn’t, we wouldn’t ever find them comforting. In the face of the darkness of the unknown after death, Izzi writes a historical novel, and Tommy uses his brilliance to try to create a previously-unknown chemical. I, too, write: and admire, in all forms, the human spirit that walks on into the blackness, as an act of defiance and creation.

;

NEXT WEEK: As an ordained minister of the Church of the Latter-day Dude, next week it’s time for me to evangelise on The Big Lebowski (1998). For our schedule, check in here.

I haven’t seen the film, but I’m intrigued with your realistic acceptance of death ending our consciousness–highly unusual for a Mormon.

I consider facing the reality of our mortal situations a basis for all belief.

Anyone who believes in the resurrection should first reconcile themselves to the fairly plain fact that without some sort of miraculous intervention that there’s no evidence but faith for, we’re all headed for death.

This is where faith starts, in my opinion.

I saw this years ago, and the only thing I specifically and immediately remembered about it was that it was visually beautiful/stunning to watch–it’s worth it just for that aspect.

As to your question of forever after, I have an experience somewhat different from other, traditional, LDS folk because I’m not married to a Mormon. What I believe is that God loves us, and wants us to be ultimately happy, and if we’re meant to be paired with the same person for eternity, God will do whatever matchmaking needs to be done, provided I do my part to qualify for that. And if that takes thousands/millions of years, so be it. To quote my Nana–eternity is a hell of a long time.

What do couples who are temple sealed think about that sealing if they are secretly not thrilled with the eternal choice they made?

Thanks for your perspective, Elizabeth. I certainly feel that it’s not impossible (in this perhaps-infinite universe) that the LDS story is accurate. And if it is: then I have no doubt that God will honour the honesty of heart with which loving couples – of whatever faith or belief – have lived their lives. If he doesn’t allow them to be together, then I want no part of his kingdom.

I should say though, I still hold our temple sealing as a sacred experience in our lives. It was a powerful moment for us both: and it is drenched in meaning within its context at that point in our lives. Nothing can take away from that. It just distils into what it really is, more clearly: an expression of love and infinite commitment between two young people. I think that’s beautiful.

Elizabeth, I’ve been thinking more about what you said:

…about immortality. I’m interested in how the LDS idea of resurrection has evolved. There used to be a song in the early days of the restored church with the lyrics in the chorus “The Resurrection day/ The dead are sleeping in their graves/ ’til the Resurrection day.”

When did the idea change from this – that we are unconscious at death, until the future miracle of resurrection: to the idea we have now, where we retain consciousness at death, in an instant transfer to the spirit world? It seems that the latter idea fits with LDS doctrine about the learning that needs to go in ‘Spirit Prison’…. has anyone else heard the song?

I could believe that at some future date, some beings could find a way to bring us back. Consciousness would be a tough thing to restore… but who knows what future miracles of science could include? Eternity is a hell of a long time!

When I watched the film (I still need to get around to watching it again), I don’t think I got the impact. I mean, I loved the music, and the visuals…and I think I got the plot and the message from a surface level…(in other words, I can read this post and think, “Yeah, nothing new there”), but it just didn’t really grip me deeply.

I remember that I had read Loyd’s paper addressing the movie with comparison to Heidegger and Wittgenstein BEFORE I had seen the movie (and so I couldn’t appreciate it then), but then I found it again AFTER I had seen the movie and it made a LOT more sense.

The interesting thing I got from it was this: It points to the yearning for immortality as an inauthentic responses to our very beings — since we are beings toward death and that in a way defines us, we have to accept this. In other words, all the time we think about immortality and how to achieve it is a distraction from the time we could be spending with each other (as the recurring scene where Izzi wants Tommy to walk with her for the first snow highlights). I don’t see the message as really dovetailing with the LDS (or any other) idea of another existence…rather, it’s more a statement about how we should live life *here and now*.

Not to be a downer, but it doesn’t have to be true that “if the LDS stories about death and love don’t speak true, then they wouldn’t be comforting.” Maybe the truth is extremely disturbing and we’d rather have a lie?

To put it in another way, I don’t like ideas like submission and ego death, so it makes certain religious paradigms rather unappealing to me. But I must admit that the reason I don’t like these things is not because they are untrue (I don’t know that), but because of something within me that, if the paradigm indeed is true, is “broken.” I don’t like the ego death implied by a concept like “nirvana” because my own ego — which is holding me back — seeks to preserve itself. Similarly, I don’t like ideas like “losing my life to gain life anew in Christ” for similar reasons.

But MAYBE, in each of these instances, or in the instance of my consciousness…the entire point is that I have to accept that one day these things MUST go.

Hey Andrew: thanks so much for the thoughtful response. I hadn’t seen Loyd’s post: I’m going to enjoy taking a good and careful look at that. Looks like you only found that to make the first comment (!! can’t believe that: looks like a great analysis) last month – so it’s happy coincidence that I unknowingly chose to write on this so soon after.

I’m not an expert on Heidegger or Wittgenstein, but I do agree that immortality is an inauthentic response to our beings: at least, the largest proportion of our beings. Physically we are headed for death, but for evolutionary reasons, we have a desire to hope for, seek and fight for continued life. I think we can be authentic to that aspect of our selves, which is, strictly speaking, physical, too: in our DNA.

When I talk about truth in the LDS stories of death and love, I should perhaps specify that I’m not speaking about an objective, physical truth, but a congruence with the channels and processes of the mind. When a narrative brings something to life in us, I see that as a variety of subjective truth that is valuable, insofar as it enables us to experience something meaningful. It isn’t absolute, and may be shed at a later stage for other truths. It’s probably a ‘truth’ that we’d rather have ‘a lie,’ and it’s that truth that I think fantasy activates: and certain religious discourses, too. It’s ‘real’, even though physical reality doesn’t accord with its literal sense. I acknowledge I muddy the waters with language here… but hey, it’s muddy no matter what! I’m a student of poetry, not linguistics. :)

I was interested to hear about the specific paradigms that don’t work for you. I wrote recently in a post linked from this one (on ‘the Sublime’) about my split response to temporary transcendence in worship… I hear what you’re saying: but perhaps because of my LDS upbringing still being fairly persistent in my bones, I respond to these narratives. Is it this tendency that makes me relatively okay with the idea of death? I’m not sure… I think I was quite egocentric as an active LDS member (and probably still am!): however, I think rational questioning has, in my experience, made me more okay with letting go of the self. I see myself as more of a part of the social system, biological ecosystem, etc… not headed for fame and godhood.

Andy,

Yeah, Loyd’s post is pretty philosophically heavy, so it may take a couple of reads, but I had been keeping track of his ideas on “eternity” before, so it was easier to understand.

Re: immortality is an inauthentic response to *the largest proportion of our being*: it gets really tricky to start trying to tease out these things, to say “this proportion of our being is against immortality and this part longs for it.”

It is possible as well that even if we can split parts of our being into for and against, that this doesn’t say much about the authenticity of immortality. We are to believe, for example, that we have a sinful nature…or we have the “natural man.” But we don’t then say that this is evidence that authenticity is following the natural man or in sinning.

(Or rather, if we do say that, then we quickly follow up with, “But authenticity is baaaaad. Cast off the natural man and become someone you’re not.)

Re: objective truth vs. subjective truth. While I think some of this gets really muddled (as you point out, all parts of us is, strictly speaking, physical — part of our DNA…all subjective truth correlates to a truth about brains and neurology, then), I think the problem once again becomes that we can find *subjective* comfort in things we ought not. E.g., the “natural man” concept. When we say “wickedness never was happiness,” most people understand that this doesn’t mean there is no pleasure or comfort in wickedness. Rather, they mean that whatever the comfort here — or whatever the lack of comfort in following commandments — one will certainly grow more and achieve more through righteous living.

So, ultimately, we really are just picking which subjective experiences we will value. One class of experiences we will call “righteousness” and the other “wickedness,” and despite the fact that people may experience something meaningful from either class, we will try to say that one should be sought and one should be avoided. That, by the way, is without making ANY appeals to “objective truth.”

Re: specific paradigms. I feel like a broken record on my blog or at Wheat and Tares, but even from the most basic: the paradigm of faith, of belief, of knowledge. Mormonism assumes that one can *choose* to believe and *choose* to have faith. If one doesn’t, then they have a character flaw that they need to work on — maybe for the rest of their lives — even if it makes them miserable. That’s the idea of “enduring to the end.” It is a submission to a kind of life path.

My LDS upbringing makes me respond to these narratives as well, but not in a positive way. I see it as exemplary of a broken system. One to which I tried to FORCE myself for way too long. (sorry to be a downer).

Re: egocentricity. One thing is this: there is a “standard” for what the LDS member should be aspiring to. Straight, heteronormative husbands and wives with children, for example. The moment you don’t fit that mold, then you come to face this idea that there is something about you that you are expected to change. (I’m giving a simplistic, yet extreme example, but to the extent that EVERYONE falls short of celestial standards, EVERYONE has something about them that must be changed.)

My problem with this is it seems to squash diversity and make us carbon copies. I mean, imagine the days when people thought righteous Lamanites or blacks or whatever minority would become white in the afterlife. (I still hear some old people inform me that in the celestial kingdom, I’ll be white.) It seems to me that to be a celestial being is to be a carbon copy. If not in appearance, then in thoughts, actions, inclinations, etc., And if I’m a carbon copy there, when I’m not here, then what is being lost? It feels like *I* am being lost.

The church would say, “Well, duh, you’re being lost. That’s the point.” I’m not so sure.

Negative experiences with the social system don’t make me all too keen to identify as part of it — or rather, recognizing that I AM a part of the social system, I lament that I’m not an integrated part but an “odd man out,” and that in order to become an integrated part of the system, I have to eliminate things that are unique for me.

Andrew S., you’re joking about people telling you you will be white after you die . . . right??

You bring up an interesting point about everyone being the same, like carbon copies. We do talk in the Mormon church about diversity, but diversity seems to refer to a VERY narrow set of criteria. So the Gospel Art Picture Kit, for instance, has a family that looks Polynesian, and another picture has a Hispanic family, an African / African-American family, you get the picture. But diversity of thought/belief? Not tolerated. Or at least not desirable.

Reminds me of a YA book I read with my oldest daughter in conjunction with a mother/daughter book club we used to have. The book is called Uglies (and it’s part of a 4-book series that is really good if you have tweens/teens). In this dystopia, everyone is an “Ugly” until you turn 16–at which point you undergo surgery and become a “Pretty.” The protagonists in the book decide they are happy as they are and don’t want to undergo the surgery and so they run away. They discover later that the surgery includes a mind-altering process that makes you always happy/content. Pretty interesting stuff for adolescents. Anyway . . .

I’ve also always been uncomfortable about the way LDS teachings devalue authenticity as an expression of the self, in favour of a ‘carbon copy’ nature. It’s the whole thing about Christ looking identical to Elohim, as Seth looked identical to Adam… supposedly, in many strands of LDS teaching, we’re all going to end up alike. Oh: except for gender differences, of course. The women get to procreate eternally while the men get to be kings. Not an afterlife that appeals to me, either.

About the ‘choice to believe’… this is a conflicted doctrine, too, I think? Isn’t there a narrative about ‘the elect’ that suggests that ‘my sheep hear my voice’: ie. we don’t have so much choice as you might think? I don’t know enough about the LDS history of these doctrinal ideas: agency is a really important idea in the Plan of Salvation… and yet, by invoking the idea of pre-existent faithfulness, it’s possible to keep agency, and have a kind of ‘election of grace’ active.

I think that in part, the scriptures are a collection of inconsistent ideas anyway. This is why there are so many Christian traditions anyway (not even counting LDS scriptures that add more ideas). So, even if there are narratives (which I do not disagree) that point to a group of the elect, these can be de-emphasized as is expedient, or emphasized when that is the case.

I’d say that for Mormons, agency is just too important to concede anything else. Even when talking about fore-ordination when I was growing up, I remember my teachers insisted that it was not predestination…just because someone was foreordained to do great things in this life, he might still not reach his potential. Just because one’s Patriarchal blessing says one thing, it’s contingent upon righteous choices.

Nicely done, Andy.

I watched this movie several years ago and the photos remind me how visually stunning it was. Also, I was in a very different place with my beliefs, it would be interesting to watch it again. I do remember feeling that Tommy’s grasping, his desire to avoid the pain of separation from Izzi, she becomes more and more lost to him.

As for eternity and what happens to us when we die, I hold both possibilities in my heart. I’m honestly not sure what will happen, but I don’t feel afraid and I know I can’t avoid pain or separation.

Heather,

forgot to check back to respond (Doves and Serpents REALLY should get comment subscription by email),

I’m afraid I’m not kidding. But this is one really nice old guy who really cares about Africa as far as I can tell (all of his talks weave it in there)…he just think that the best thing that’ll happen is that in the afterlife, all people of African descent will become white. He’s not TRYING to be offensive or malicious or anything.

I remember when I was in junior high seeing some people read that series, but I didn’t…

then again, I can’t use this site as is…I just figured out how to use the reply feature…

:) Thanks for the feedback Andrew. I’ve enabled the ‘subscribe to comments capability. There’s a link under the box where you add a comment now, for managing subscriptions, too. Enjoy!!