;

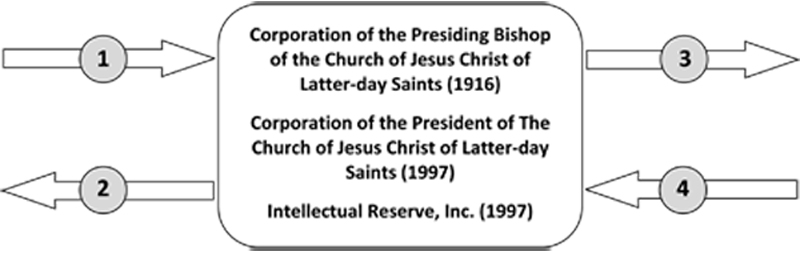

In 1838, after cycling through a few different names, Joseph Smith settled on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Brigham Young incorporated the church by legislation in the provisional State of Deseret as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the State of Deseret only existed for a couple years and was never recognized by the U.S. Government). When Mormons refer to “the church,” they are referring (probably) to the three legal entities in the above box (all incorporated in the state of Utah in the years listed). The Corporation of the Presiding Bishop acquires, holds, and disposes of real property; the Corporation of the President receives and manages money and church donations; and the Intellectual Reserve holds the church’s intellectual property (copyrights, trademarks, etc.). The church also owns a number of non-tax-exempt corporations (go here for a Wikipedia entry on the Finances of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

That’s the boring stuff. The upshot is that the church is, in many respects, a legal entity (or entities) just like any other large corporation. It has an office building, lawyers, an ad firm, a payroll to meet, accountants, administrative assistants, buildings, desks, computers, etc. People show up to work for it on Monday morning. It produces a product. And like any other modern corporation, it has a revenue stream. Let me make a few observations:

1) In the history of the church, neither cash nor any assets of any kind have simply materialized in its bank accounts or on its balance sheet. Everything the church owns can be traced to real-world (and entirely ordinary) exchanges. The absolutes of accounting apply to the church as much as they apply to any other organization.

2) The church can go bankrupt. It almost did. Luckily, the church was able to dramatically increase it’s revenue and pay off it’s debts. We’ve all heard the story about Lorenzo Snow and tithing, right? There is a little more to that story than obedience serving as an effective rain dance.

3) Unlike other organizations (and other churches, in particular), The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has consistently taken in substantially more in revenue over the last 100 years or so than it has paid out in expenses.

4) The church does a remarkable job of keeping expenses down (by having lay members, on a unpaid volunteer basis, provide most of the input necessary to run the church on any given Sunday) and keeping revenues up (by getting members to contribute tithing).

There are four numbered arrows in the diagram above (numbered 1-4).

Arrows 1 &2 represent exchanges through which the church acquires control over the resources its need to deliver its religious product. For example, the church may pay an ad firm a million dollars for an ad campaign, or buy a computer for $400 from Dell, etc. Not all exchanges involve money, however. It may also exchange feelings of contributing to a cause, or belonging to a group, or a promise of future rewards in the hereafter, etc. for volunteer hours that it then utilizes to provide certain services (tours on Temple Square, for example). Arrow #1 represents an incoming stream of resources (physical resources, human resources, buildings, tables, chairs, volunteer labor, etc.). Arrow #2 represents what the church has to exchange to acquire these resources.

Arrows 3&4 represent exchanges on the demand side with “customers” or members. Arrow #3 is the church religious “product.” This is what keep members happy–and makes membership worth it. This is what attracts new members. Arrow #4 is what members are willing to “pay” for this product–generally in the form of tithing (but also in in-kind donations or volunteer labor). Arrow #4, in other words, is the church’s revenue stream. Taken together, these four arrows, once labeled properly, represent the church’s business model.

So here it is. The one inmutable law of organizations. As long as #4 is greater than #2, the organization will grow (and continue to amass resources). If #4 is less than #2, the organization shrinks (and its stock of resources diminishes). Unless this inequality is corrected, it will shrink until it ceases to exist.

When you approach the church from this perspective, a number of questions come to mind. Why has it been so successful keeping #4 greater than #2? Is it its structure? Its internal incentives? The nature of its religious product? Does its opacity with regard to its finances help it or hurt it? The church hasn’t released a financial statement in the U.S. since 1959, although it does so annually in England and Canada, because it is required by law to do so. How much of the behavior of the organization, in a strategic sense, is driven by its business model (Wilford Woodruff’s defense of the 1890 Manifesto, for example, explicitly cites protection of the organization’s business model as a primary driver for the decision to end polygamy). In the end, does viewing the church through this lens make it more understandable?

[Last Post: 18 The Polygamy Problem]

You need to correct the year in the first sentence.

Yay! This is my favorite column, happy that it is back. I am typing this about 3 blocks away from Temple Square, and 2 blocks from the multi-billion dollar mall/condos/hotel development called City Creek, which has been under construction for years. I am excited for it to open, but it is also weird for me.

On the other hand, it is unsurprising that an organization run by businessmen would closely resemble a business.

As an accountant, it makes perfect sense. It’s a business model that all businesses (including not-for-profits) follow. I think if more religions followed a model like this, with planning and intent inherent in the model, there would be fewer start-up churches that crash ridiculously down.

I also like that it was posted here, more people (not business majors) need to be aware that this is how things work. Not only now in our 21st century capitalism but it’s how businesses always have worked. It’s how the Catholic church has worked – though they do have a history of simply taking the riches from people and slaughtering them in return. But true to form, they had to first equip their Knights with armor and weapons in order to get the riches of the slaughtered. And if the riches weren’t enough to compensate for the cost of the armor and horses then it wasn’t worth the time for God’s Army to punish them.

The really interesting key is arrow #3. What do you receive from them? That’s where you throw in the emotional debate that is only solved on a person-by-person basis. No one can claim that they have the answer for someone else. It’s how you measure the intangibles that solves the dilemma of whether it’s worth it. And I’m very impressed with this article that didn’t attempt to put any dollar sign on the value of #3. Outstanding journalism that described a set of facts and had some leading questions, but didn’t attempt to answer them. Wonderful job!

Well said. This blog is going on my RSS feed. Found it by accident through Bing.